I’ve been finding myself in a bit of a hole recently where my first response to anything, and the first words out of my mouth, are always an instinctive ‘I’m sorry’. Whether I have done something wrong or not, whether someone is accusing me of something or not, I just can’t get the words ‘I’m sorry’ not to be the first ones that immediately leap to my lips. Now, owning when you need to apologise is a really important thing. The thing is, that there are a lot of consequences to unnecessary and anxious apologising that I don’t think we necessarily recognise. After all, what does it matter if we say sorry too much? No one is hurt by the words ‘I’m sorry’. Is that true though? After a particularly anxious weekend last week I spent some time thinking about how apologising too much can actually be a leadership issue, and what steps you can take to reduce the downsides if this is something you are impacted by, like me.

It can make you come across as weak

Leadership can be challenging at the best of times, but in a resource limited setting with competing pressures, it can feel more challenging than ever. Those you are leading need to feel secure in your direction of travel and protected in your leadership.

Despite authenticity being important, being an anxious apologiser can come over as weakness and something that can be exploited by others. It can come over as not owning your time, boundaries, responsibilities, or actions. Worse than that, it can also make those you lead feel more uncertain, depending on the context of the apology. Owning up to mistakes and proportionate apologies are great, inappropriate ones, very much less so.

Makes setting boundaries more challenging

One of the things that I am super aware of is that my anxious apologies make boundary setting less easy. I am allowed to take time off sick or to be on holiday, I should not feel the need to apologise for it. Doing so makes others feel less able to also take the time they are owed. I am an emotional person. I wear my heart on my sleeve. In many ways, I believe that makes me a better leader. I, therefore, need to stop apologising for trying to be myself rather than attempting to fit some predetermined mould. If I don’t feel I can be authentic, it makes me a lesser leader and means others will also feel like they need to hide who they are.

You may accept culpability even when you don’t

Another thing about anxious apologise is that your immediate response can end up making it look like you are taking responsibility for something which you actually aren’t. A recurrent example of this one, for me, is when someone takes action and ignores advice/guidance, and I end up apologising for not providing sufficient clarity. In reality, it was up to the individual to seek additional clarity if required, not for me to be psychic and try to predict their actions. Just one example of an easy trap to fall into.

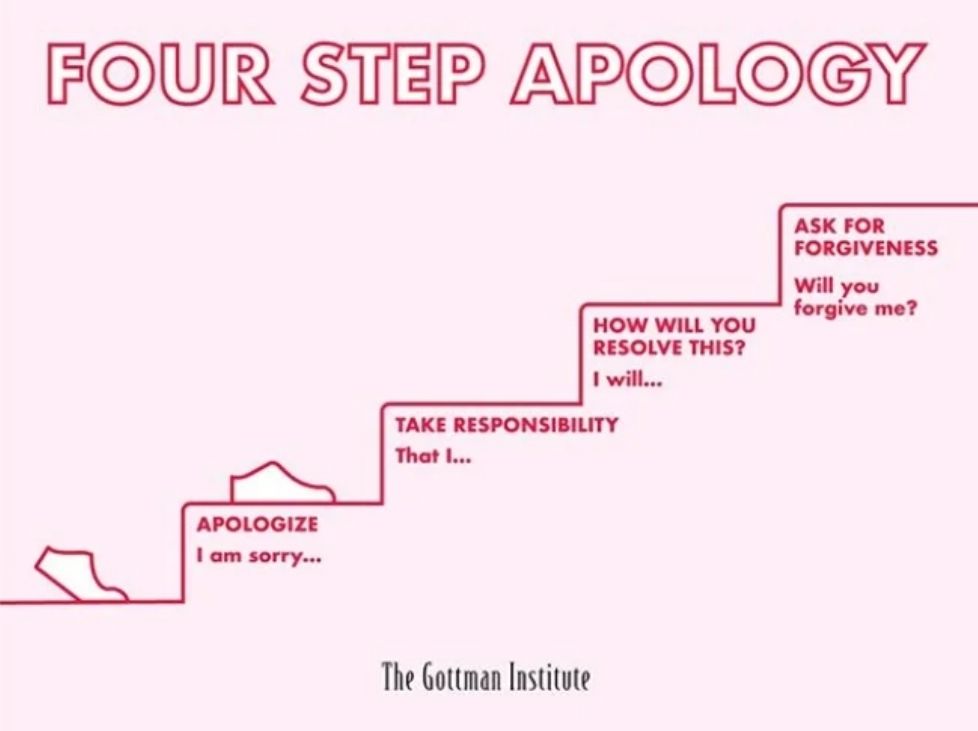

It can make genuine apologies feel less authentic

This is a big one for me. If you apologise all the time, as an auto response, it can make those moments when you choose to do so consciously feel like it has less impact for the person receiving it. Making sure those moments where you need to own your actions and learning are undertaken with sufficient thoroughness helps, but avoiding using apologies as punctuation is a longer-term change.

You may end being annoying to be around

Speaking as someone who does this a lot, I hear from many of my friends just how annoying it is. A favourite quote of Mr Girlymicro to me when I get in a particular space where I constantly need to be told it’s OK is ‘stop apologising, it’s a sign of weakness’ from the film Little Miss Sunshine. It makes me laugh every time and reminds me of how much the required back and forth is an energy drain on everyone involved. Take a deep breath and step away from the spiral, and acknowledge the costs you are placing in others.

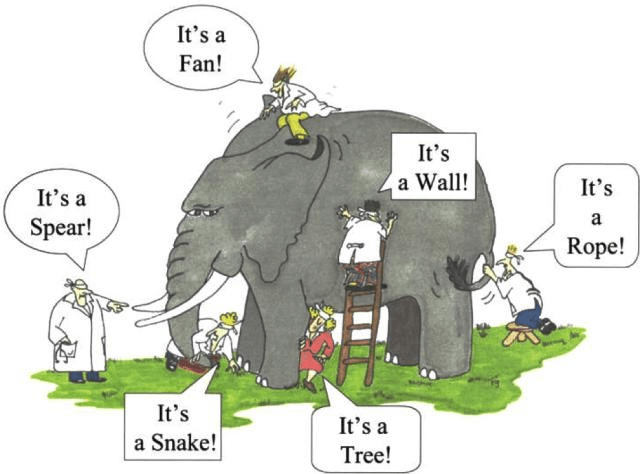

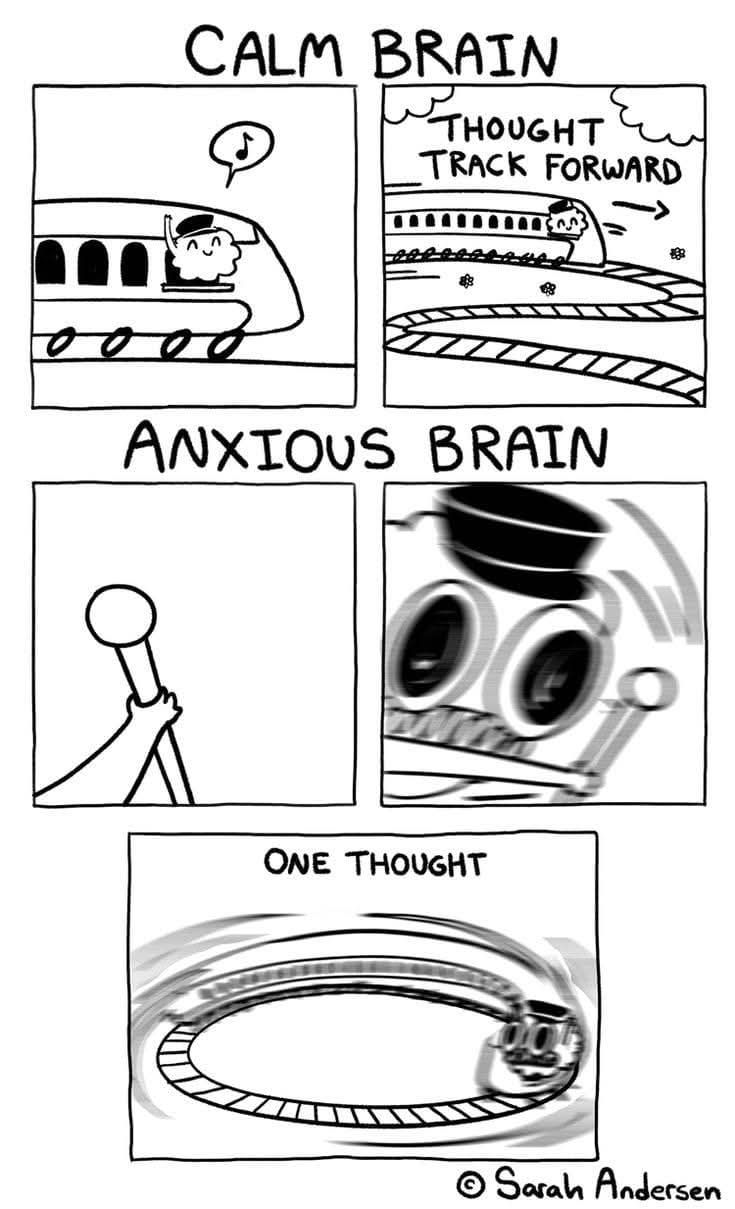

May make your leadership confusing

Another way that anxious apologies can make your leadership confusing it that they can work to actively derail trains of thought. They can end up de-railing conversations, so they become all about a single thing rather than the original focus of the discussion. They can make your communication less clear and end up meaning that key points are obscured, or worst of all, forgotten by all involved. As clear communication is a key foundation of good leadership, this is good for no one.

Conversations that are not about you can pivot

I had a moment last week when I got hit from out of the blue with an emotional response to a conversation. This meant that a conversation that should have been about me offering support, guidance, and clarity, became all about the people involved comforting me. This is a disastrous thing to have happen. My immediate response is then to apologise more for letting it occur, but this then drives the cycle. Stepping away from it. Knowing you should do better and reflecting with yourself why it occurred is the only real remedy you can offer.

So, how can we do things differently?

Acknowledging that this is not a healthy habit or coping strategy is a start, but what we actually do about it in order to do it less or limit the impacts on our leadership?

Listen to your frequency

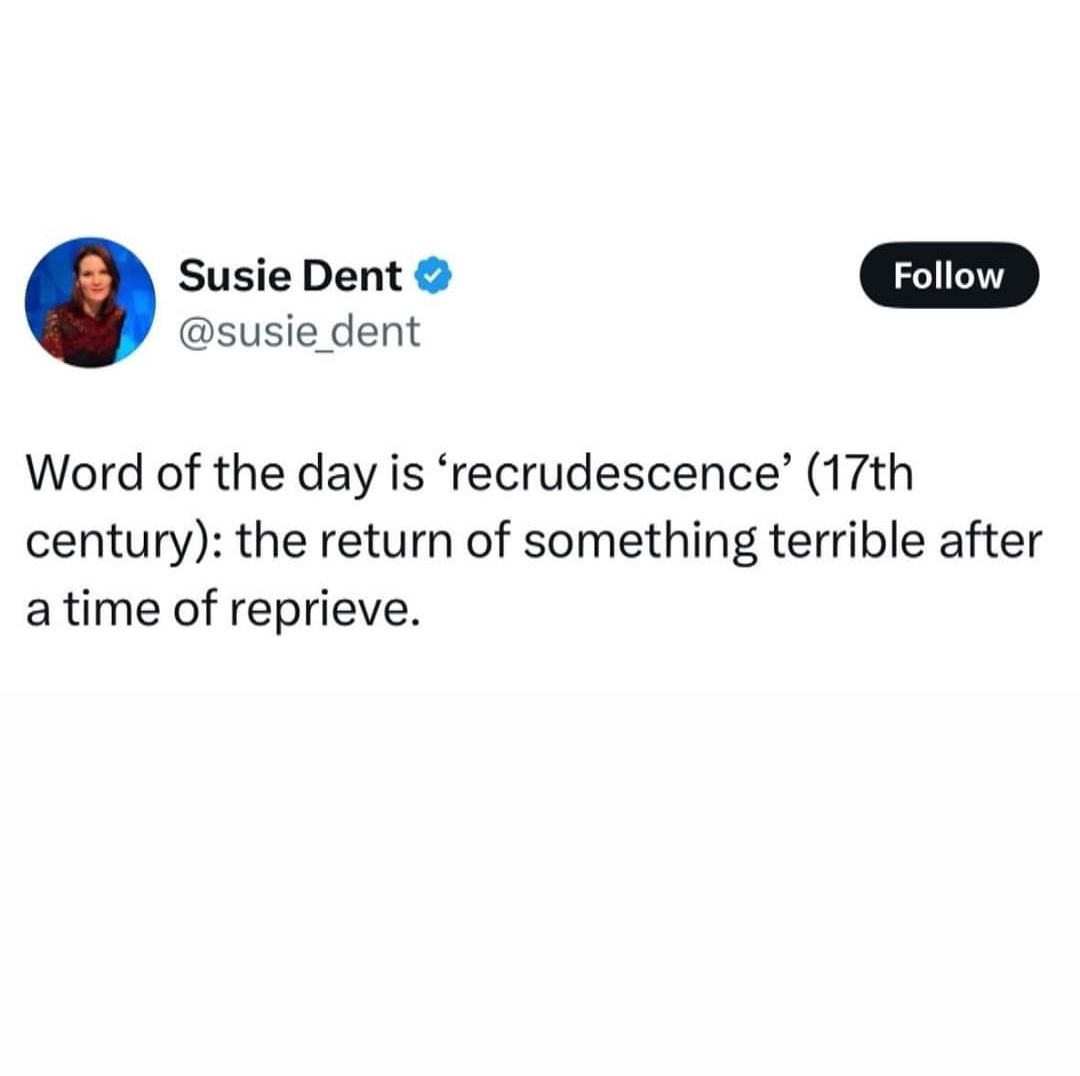

One of the primary actions is to be aware of the frequency of your anxious apologies. For me, at least, this isn’t an always-on/always-off thing. It comes in waves depending on other things that are happening and my general levels of anxiety or confidence dips. Knowing when you are going through a bad patch enables you to focus some resource on reduction, especially in risky or high stakes moments. Doing the constant apologising at home may be annoying. Doing it in the wrong situation at work could have much bigger consequences.

Be aware, especially during high stakes moments

There are moments, for both you and your leadership, where being perceived as weak or accepting ownership when you don’t, can have significant impacts. In these moments it’s crucial to be aware of where your head is at and your tendency to undertake this behaviour. These high stakes moments tend to also be high risk moments, so if you apologise as a stress response, you are even more likely to fall into an apology during these encounters.

In order to help with this, one of the main things I try to do is just take a beat before I open my mouth. Those of you who know me probably know this isn’t my strongest skill. Mouth open, should be shut. At times like these, though, it is so important. That breath allows me to sense check my response and remove the work ‘sorry’ from my automatic vocabulary. It allows me a moment to try and re-phrase my immediate thoughts or dialogue to make it more in line with my core meaning. It helps me avoid throwing myself and others into an unnecessary bear pit.

Don’t let others take advantage

It is also worth remembering that it is not just you that notices this behaviour. In the past I had a colleague, who was perhaps not my biggest fan, who I realise in hind sight would almost set me up in scenarios to take advantage of my tendency to accept responsibility readily. If your apologies do come across as a sign of weakness, and you work in a high competition environment, then this is a risk. Taking time to understand how others respond to your anxiety trait (irritated, sympathetic, exploitative, etc) is an important part of learning how to manage your own behaviour. Know when to bite your tongue and stay silent despite all of your instincts telling you otherwise.

Try to embed change

One of the easiest ways (although still far from easy) to manage this tendency is to try to find other ways to respond. Ways that still allow you to feel you have responded but that are less likely to be interpreted as you taking ownership all the time. Embedding these changes consistently, even if you are going through a particularly bad spell, can make it easier. Language is a learnt response, and much of it is based on habit. Getting into a space where you only apologise consciously for things that actually require it is a habit worth gaining.

I’m still not good at this. I think it’s an area of constant improvement. I have found it is easier to try and embed this shift in written communication first, and then it comes a little easier with verbal reinforcement later. Just take it one conversation at a time and see what works best for you.

Find trusted friends

For me, one of the best ways I have to manage this is to find my people, my trusted friends. There are two main reasons for this. One, Mr Girlymicro loves me enough to cope with me apologising, me talking about apologising, and me agonising about whether I need to apologise, for the hours it sometimes takes to get me to work through what is going on, and to then move past it. I also have some key people in my life who I know I can text and be ‘this happened, do I need to worry’, and who I 100% trust in their response to guide my actions. The second area where I find these people really useful in my life is that they will flag to me, when I lack the self awareness to notice, when I’m starting to increase my anxious apologising, so that I can be more aware of my own emotional state and the impact it is having. Knowing that others have your back, and can support you, even when you are not aware that you need support, is a real gift in this life and if you have access to those people make sure you hear what they have to say.

Be OK with not always getting it right

You are not going to get this right all the time. There are times in my life when I don’t manage to get it right even most of the time. Treat yourself with the grace that you would give to others. Anxious apologising is driven by, guess what, anxiety. Don’t drive your anxiety further by diving deeper into the rabbit hole and stressing about things you can’t control. It happened. You may be able to fix it, you may not. Nothing is to be gained by stressing about it, and the best cure for some of that anxiety is to take action if you calmly decide there is an action to be taken. The irony of me writing these words is in no way lost on me, as I can never stop the resulting panic, that doesn’t mean that the logical part of my brain does not acknowledge that it is the right move however. Try choosing grace over guilt whenever possible, as you will be a better person as a result.

Invest your energy based on circumstance

Having acknowledged that you won’t get it right all the time, a key thing is to know when you MUST get it right, or when to invest energy in order to bring your best self. We’ve talked about being aware of your high risk moments, and if you only have a certain level of energy resource to invest, then this is where to choose to spend what you have. When I’m working through a significant anxious period I can’t keep it together at all times, I just don’t have that level of cognitive resource. I have to have my safe people who I can spend time with, so I have periods where I can just let myself be and work through how I’m feeling. I also tend to stay away from people or situations who I don’t need to interact with at that time and tend to make me feel less safe/triggered, in order to not fuel the situation I find myself in. No matter what is going on, trying to be self aware enough that you make good decisions to help yourself through is definitely worth the resource requirement.

Don’t forget to deal with the underlying drivers

At the end of the day, however, it’s important to remember that anxious apologising is a symptom and not the cause. It’s really easy to focus on the symptom that is taking up you energy and cognitive space, when really we need to be stepping back and seeing what is driving the current situation. In my case, it’s often when I’ve not recognised that my health is not great and anxiety is often secondary to flares, lack of sleep and generalised discomfort. That said, I am also of an age where being peri-menopausal is definitely a thing, and my hormones are definitely writing their own story right now, with little input from me. Whatever the reason, making sure that you try to understand what is driving you means that you can start to focus on the root cause of the problem, not just react to the moment, giving you both actionable intel and hopefully a way out of the way you are feeling. None of this stuff is easy, but know that you are not alone in managing it or finding a way forward. If you need one, I’m always happy to be your safe space.

All opinions in this blog are my own