As I continue the slow road to feeling more like myself again I thought it might be nice to have a guest blog from the wonderful Sam Walker on some of the things that have been happening in the research Girlymicro world, so you know I haven’t been entirely resting on my laurels and eating copious amounts of chocolate. One of my favourite papers ever is based on the release of cauliflower mosaic virus DNA into a ward space, to support prospective tracking of where organisms go, instead of trying to guess based solely on where we find them without origin data. Due to a number of technical factors this approach to improving environmental transmission pathways hasn’t widely been repeated………..until now!

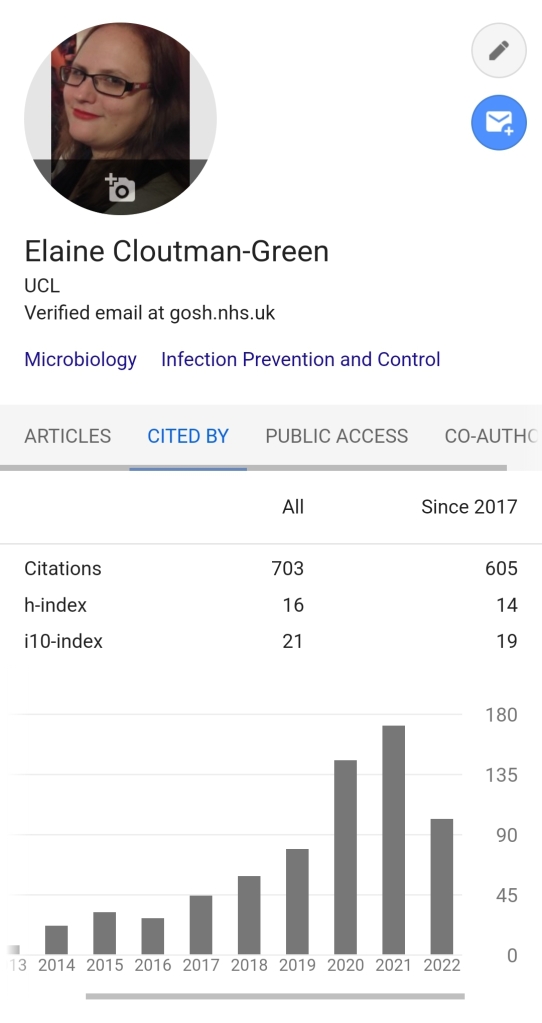

Sam is a Doctoral Research Student whose research focusses on the development for environmental surface monitoring protocols to inform clinical risk assessments and infection control procedures. His project aims to develop an evidence base for the presence of nosocomial pathogens in the hospital environment, as well as model the transmission of pathogens in clinical spaces. He obtained an MBiol degree from Aston University in 2020, with projects focusing on C. difficile spore germination.

Infection Control Research

“I imagine the swabbing part will be easy, it’s the data processing I’m worried about”. I think I said this about a month before the largest, and final, sample collection campaign in my PhD project. Famous last words.

A little bit about me – my name’s Sam and I’m one of Elaine’s PhD students. I’m finishing off my third year now (crunch time!). My project focusses on developing evidence-based surface sampling guidance to inform infection prevention and control practice. Practically, this involves collecting a range of samples from different clinical spaces and seeing that they can tell us in terms of microbial communities and microorganism dissemination, then using this information to target guidance for designing the most effective surface sampling protocols. In order to best inform this, we designed a study which looks at the movement of microbial surrogate markers through several different wards at Great Ormond Street Hospital. This involved a lot of preparation and many evenings swabbing sites across four wards. As of last week, all this sampling work has finished and I thought I’d share a few reflections on what the experience of conducting research in an active clinical space was like.

Working across settings is amazing!

For many projects focusing on clinical practice, particularly ones relating to IPC, working in collaboration with a clinical institution is absolutely essential. As my project involves collecting evidence from clinical settings to then process and develop into guidance, in my case this work wouldn’t be possible without this collaborative approach. As the end goal of my project is guidance that will inform clinical practice, not only is it important that the evidence is gathered from clinical settings, but it’s essential we understand the routine challenges faced by IPC teams. We can design the best set of guidance with all the technical detail in the world, but if we don’t take into account every day IPC challenges and what implementing this guidance will actually look like, then in a way it would fall flat. Being in the clinical space also opens up the possibility for conversations with the people who live and breathe IPC all day – the hospital staff! Informal discussions we have had over the course of this most recent sampling project have given me completely new insights and ways to view the work we’re undertaking which I never would have thought of otherwise! Getting this insight from working in clinical settings will ultimately improve both the quality and utility of the work we produce.

Stepping out of my comfort zone

As a lot of project is lab-based, the trips outside of this setting into clinical environments can be a bit of a shock to the system. I’m used to, and probably most at home in, a quiet laboratory space with a few other people at the most, maybe the odd visitor and the trusty PCR machines. The majority of the time I make the journey from UCL to GOSH, it’s to meet either with Elaine or other members of the IPC team, or maybe to pick something up from the microbiology labs there. When it’s time to collect samples however, this is a completely different experience.

The units we looked at in this most recent piece of work we did were two outpatient and two inpatient wards, serving different patient populations. One of the first things I really noticed was just how different these wards all were. I knew that there would be some big differences, for example I knew that the cardiac intensive care unit would be a very different experience to the oncology day care unit. What I didn’t necessarily expect however, was just how different the two outpatient wards would be from each other, and how different the same ward could be on different days.

With these differences came a different way to approach the research at hand. For the outpatient units, that often meant waiting until all the bed spaces were free so we could go in and collect the samples from the environment. This wasn’t always possible though, and sometimes we just had to accept that we weren’t going to get all of the samples we set out to gather. This took quite a while to get used to – my inner laboratory scientist was wincing at the thought of lost data points. Being able to put this to one side and carry on was a skill that took a while to master, particularly when sampling with a team. No-one will thank you when you’ve been on the ward for an hour and a half and you propose “just waiting a few more minutes” to see if a bed space will become free. Having that skill to just move on however turned out to be very useful when collecting the data, as it meant we could focus more effort in the areas we could collect samples from.

All this boils down to how the space is used completely differently. The hospital is first and foremost for providing care to patients, and as a researcher I have to acknowledge that I am a guest in the space. Understanding and accepting that we won’t always be able to collect all of the 65 or so samples we planned to on a given day is just part of the process when conducting sampling in the real-world hospital setting. At first, I remember feeling like this may be frustrating when it came to analyzing the data, and that it would make interpreting my results harder due to data gaps. However, looking back on it now, I actually feel it makes understanding the story the data tells easier, and much more insightful. Being able to relate the information we gathered to how the space was used at the time of collection, even where samples could not be obtained, just makes the story all the more applicable to real clinical practice and, in this case, how microbes could move through the clinical space under all sorts of conditions.

Anticipate the challenges

While embracing the dynamic environment of the clinical space is really important for putting data gathered in these settings into context, it doesn’t mean that there isn’t a fair share of challenges with it. Before I began the sampling campaigns, both my supervisors absolutely insisted that I pre-planned every tiny detail. Down to the exact number of extra swabs I would take for each day. And I cannot think of better advice when it comes to performing this sort of work. Planning is absolutely everything. One of the reasons missing some data points during collection didn’t impact the overall quality of the data was because we anticipated that we may miss some points each day, so planned to take extra to account for this. We planned a detailed sampling sheet, so we could not only check off samples as we took them, but could make notes as we went around the ward on the environment to help with the downstream analysis. I cannot stress it enough; thorough planning made the whole experience so much better.

One challenge of conducting this piece of work was the intensity of the settings. I have a very much academic background, having done my MBiol degree and gone straight into my PhD. In other words, I have no clinical training whatsoever. This wasn’t so much of a problem in wards which were not high dependency, however I really noticed this lack of clinical exposure when we did the sampling in the cardiac intensive care unit. I knew it may be a difficult experience, given the nature of the ward we were going in to, but it still was a shock the first day of sampling there. I’m incredibly grateful for the team I did this part of the work with, who had the experience to navigate the space as well as make sure I was alright being in the setting. I think that this support, alongside taking some time to reflect on the overall experience, was invaluable for this particular component of the work.

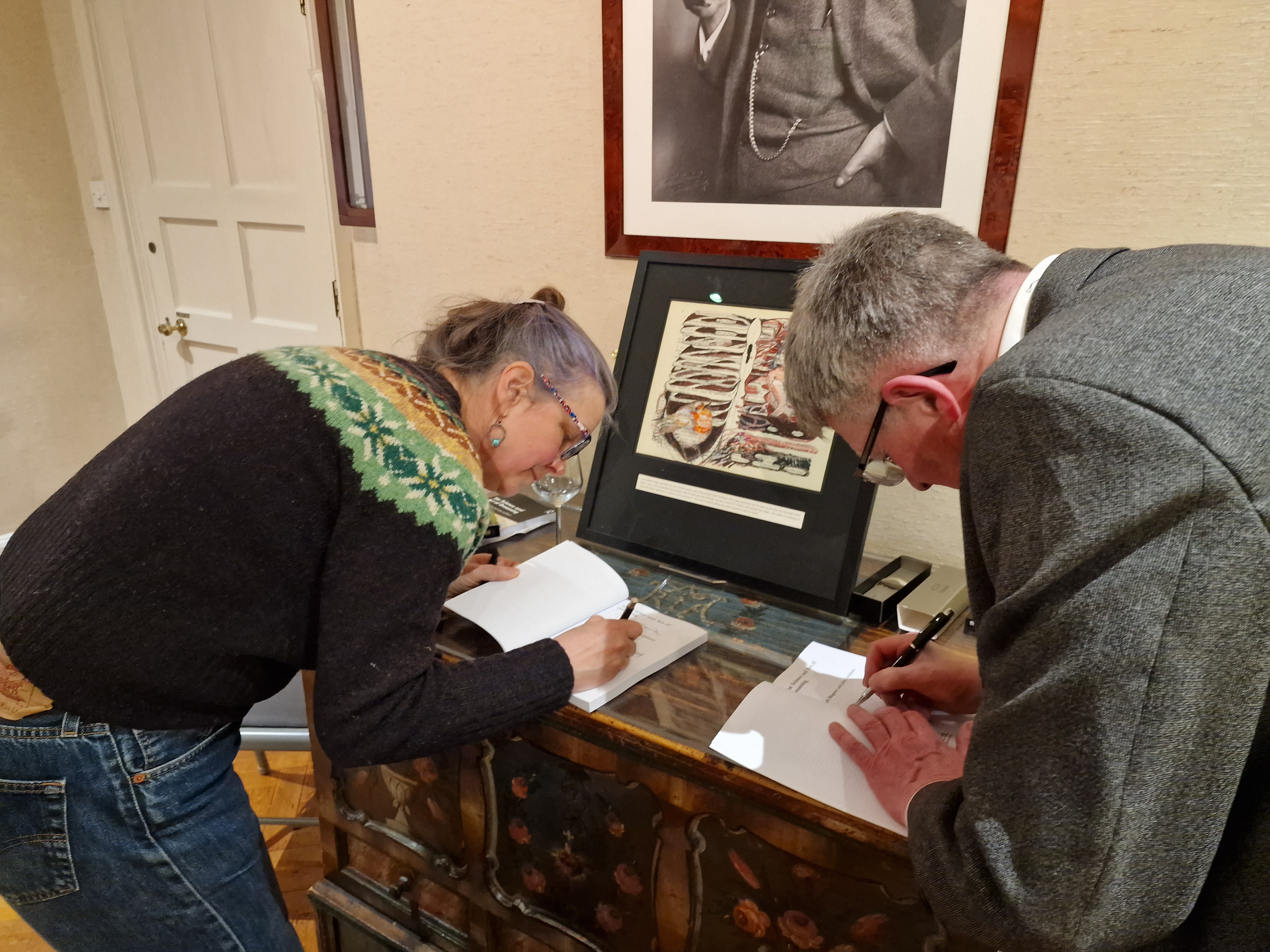

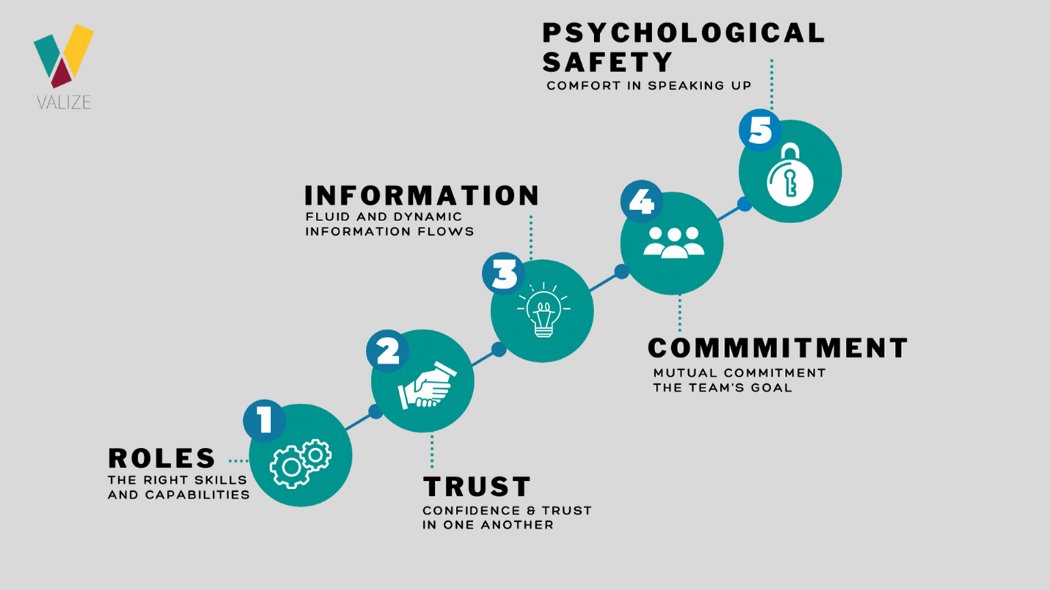

This leads me on to the other absolutely key point for doing this sort of research – having the right people with you. As academics, we often won’t have been trained in clinical practice. This can not only make some clinical spaces quite intimidating, but also can make them hard to read. For example, without a clinical understanding of what is going on in a bed space, it can be hard to know whether to ask if it’s alright to take a swab of the bed rail quickly, or if you should leave the space and move on. Having people with you who can help read these situations is so important, both for help with collecting the data but also for supporting the researcher. Another massive benefit I noticed was the links formed between me, the researcher, and the ward staff. Having someone involved who has experience in both worlds can really help break down any barriers on entering the space and help everyone understand the work that is being done, and how it relates to the ward.

Top tips for laboratory researchers gathering samples from clinical spaces

So, having said all that, my top tips on performing research in clinical spaces as an academic are:

- Planning is everything!

- Anticipate and embrace the unique challenges of this sort of research

- Have a good team who can support you in the clinical space

- And finally, get involved! Undertaking research in clinical settings is very rewarding and I would highly recommend it wherever possible!

All opinions in this blog are my own