This is not the post I’d planned to write this week. I don’t think it had really been on my mind. That’s often the way of these things however, thoughts that have been lingering without notice sneak up on you and call for attention.

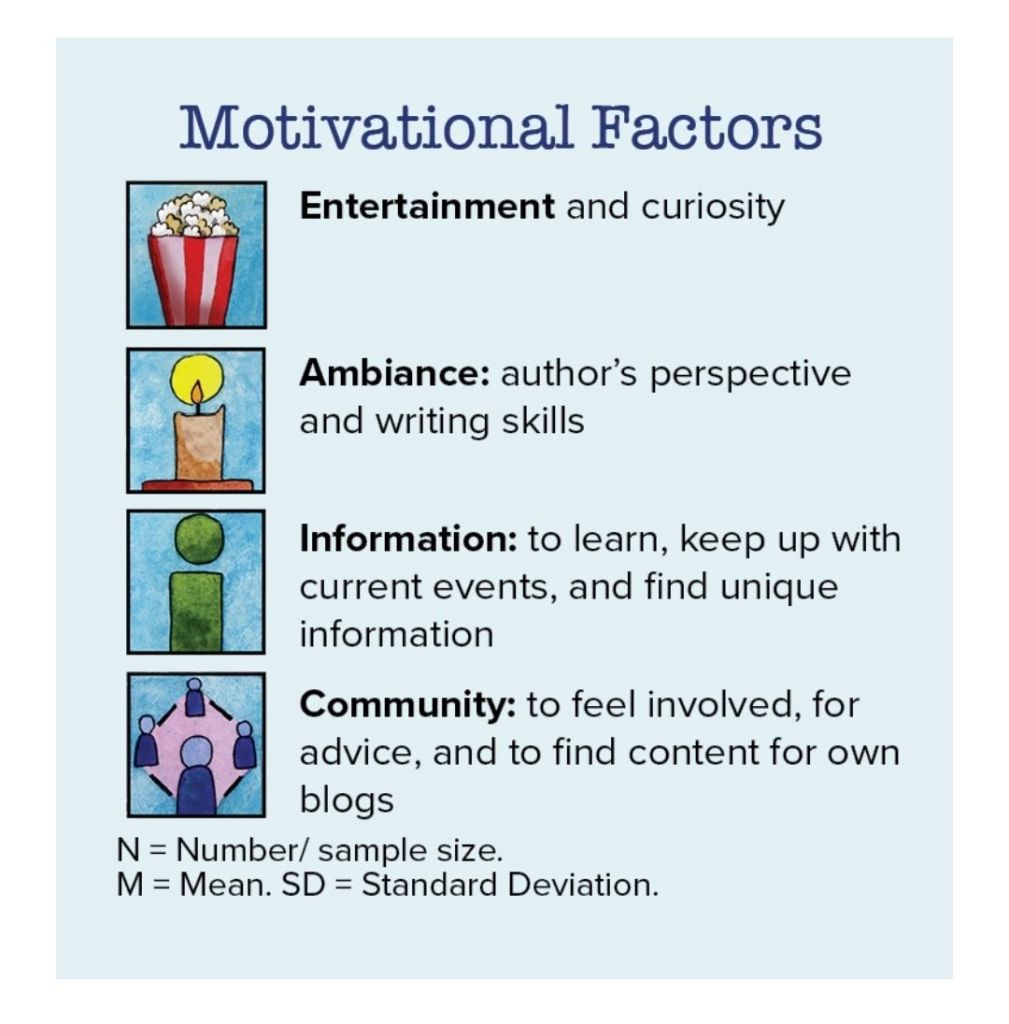

Last week, I had a meeting with the wonderful Vicky Payne and talk came around to blog writing, but also to how much we both missed the twitter communities we used to have. The supportive space, where you felt like you could share in an authentic way, and how the community really felt like it was there cheering you on. This blog was built in that community space, and it probably wouldn’t be what it is now without the support and positive reinforcement that that community gave it.

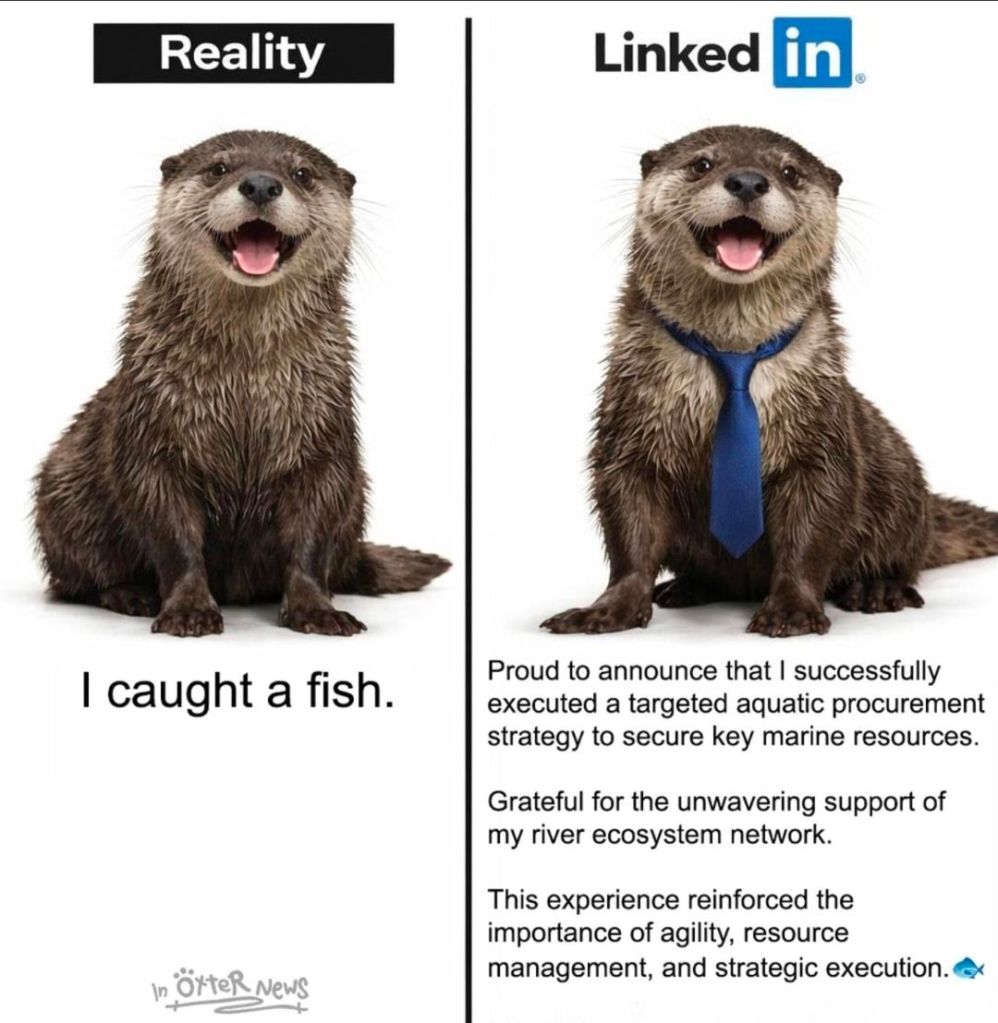

We then moved onto where we tend to post and share now, and this led us inevitably to LinkedIn. I felt like I had to share how LinkedIn feels like a very different space. That makes sense. It is a professional platform that was developed as a way of people connecting to find roles, form business connections and turn those into opportunities.

Let me start by saying this isn’t an ‘I hate LinkedIn post’. I’ve been a member on LinkedIn for years, it’s more about the change that occurred in our terms of reference, and I for one did not notice.

Like most people I used to post now and again. I’d use it as a nice way to keep up with colleagues and those in similiar specialisms. Then the decline of Twitter happened, and the ethical challenges of that meant that we all left in droves. There was a social media and connectivity hole that needed to be filled. Many of us tried alternate spaces such as Bluesky and Mastadon, but after a promising start they stalled, as many of these things do. To me, that during this time it appears that the way people use and access LinkedIn also changed. Its use expanded and changed in order to somewhat address this need. The problem is that many of us shifted our use without really taking the time to realise that it was in no way a like for like switch.

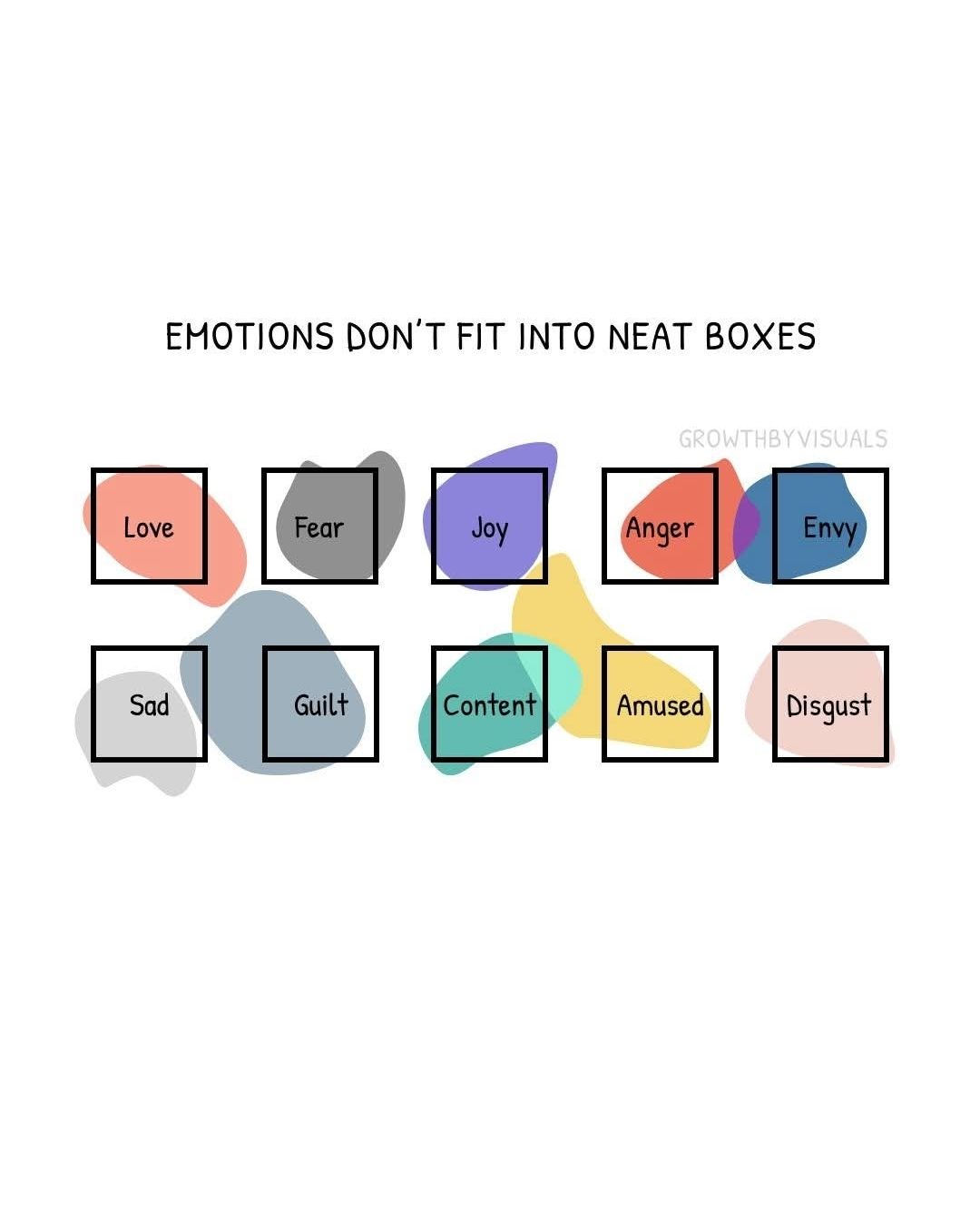

After a conversation that triggered a lot of thinking and then logging in this evening and consciously monitoring my responses and feelings linked to what I saw, I had somewhat of an epiphany about one of the reasons I’ve been struggling lately. LinkedIn makes me feel bad. With this in mind I thought I’d write about why I think that is and what I think I’m going to do about it.

How does it make me feel?

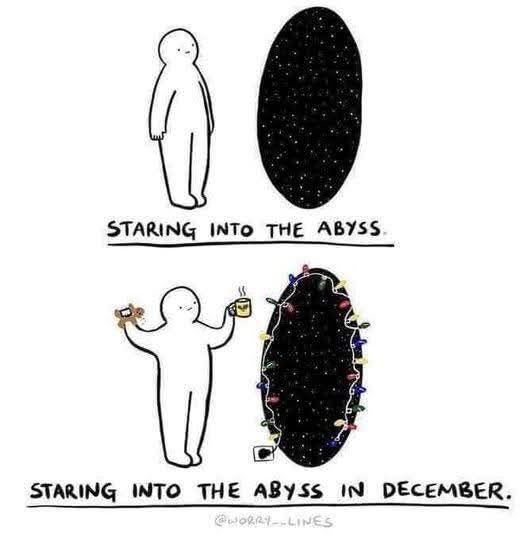

As someone who needs to be pretty active on social media, not just linked to this blog and book writing, but also because I believe that visibility and public engagement matters, I’ve not been feeling great lately and some of that is definitely driven by the social media space I inhabit. I don’t feel enough right now. I don’t feel like I achieve enough. I feel like I’m like the last runner in a race I didn’t know I’d signed up for.

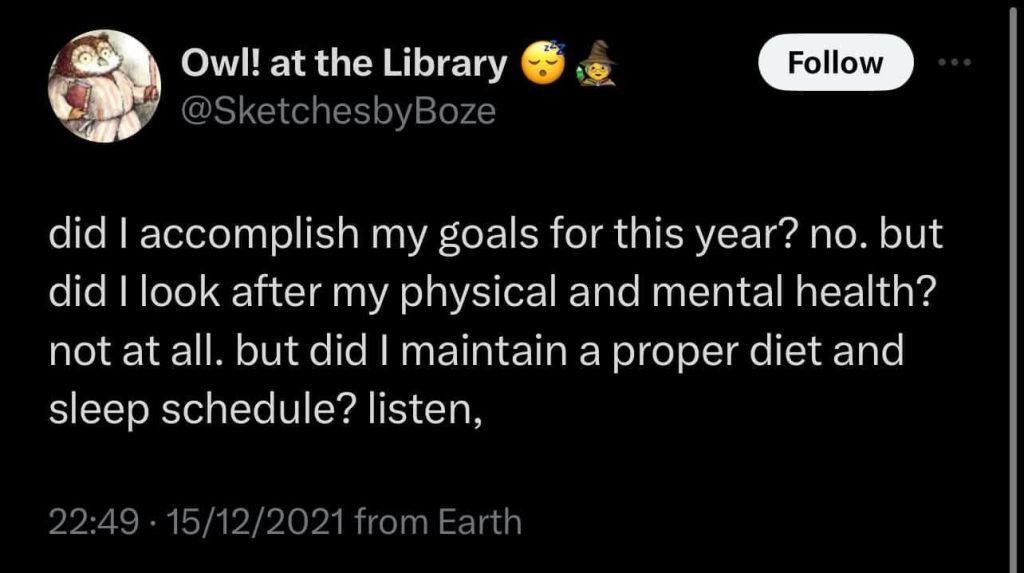

To have things seen by others on LinkedIn you have to log in, react and post regularly, otherwise your content just doesn’t get shared and seen by others. The algorithm rewards engagement. My use of LinkedIn has therefore increased. This is, in itself, not a problem. The problem is that that means everyday I see a stream of amazing achievements. People knocking it out of the park. Everyone doing more. Achieving more than I could dream of doing. When I say that that is a problem, it isn’t really. I love the people that I’m seeing achieve and have such impact. It is inspiring. At the same time there is no balance to the constant stream of highlights. It triggers the ‘must work harder’ ‘must achieve more’ part of my brain, and I have to say that those parts of me are not the healthiest parts. Those are the parts that respond to emails at three in the morning, that didn’t have a weekend off in three years. The parts that lead to a world of well being challenges as I fail to sleep or eat properly.

Bear in mind I acknowledge that this is a me problem, not an issue of the platform or those posting.

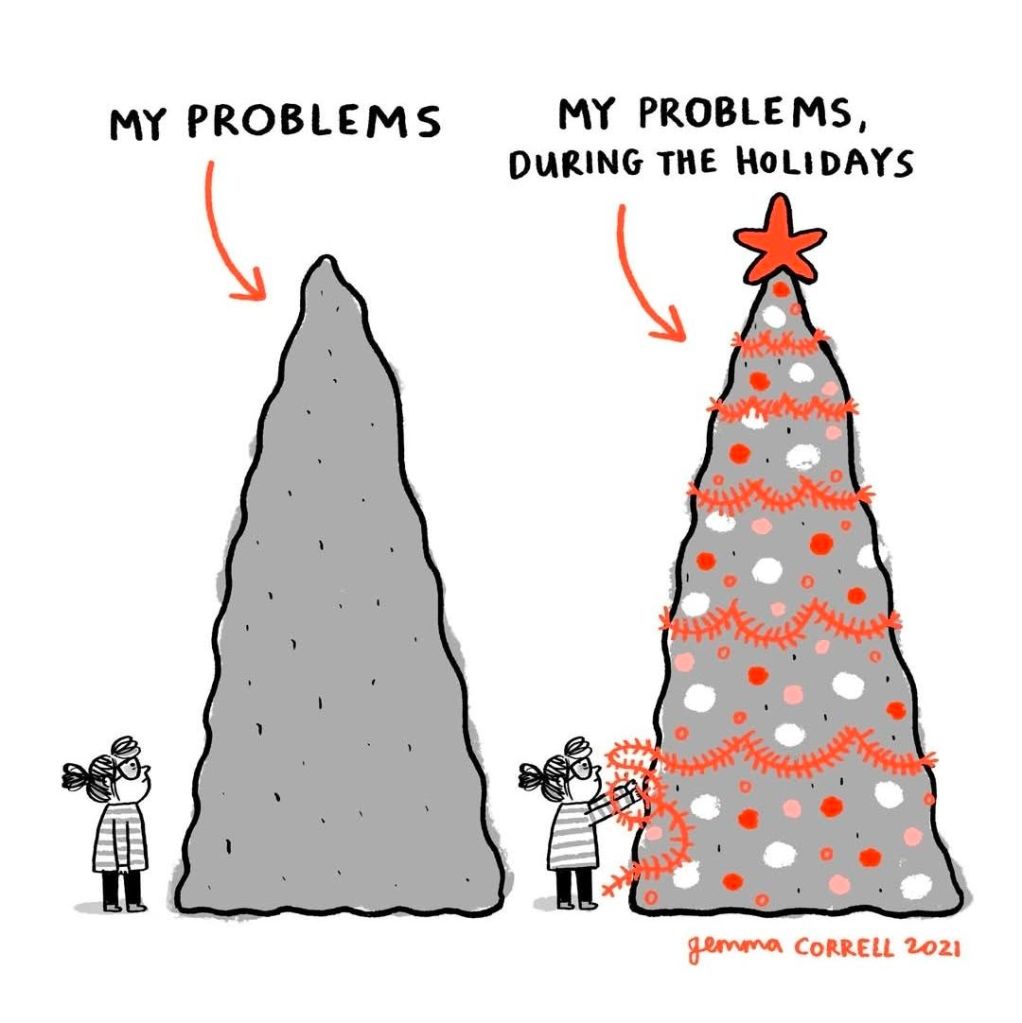

There’s a lot of uncertainty around

It is important to acknowledge that some of this response is highly likely linked to the uncertain times we are living in. For the first time in my career of over 2 decades the NHS is undertaken wide scale job cuts, with pushes for voluntary redundancy, and the previously unheard of compulsory redundancy processes. The need to show value, to show that you are ‘good enough’ is very much in my mind at least. The self doubt and questioning that working in such an uncertain space brings on is even more amplified when you see and inevitably benchmark yourself against others.

For me, as an over thinker, that makes me feel even more at risk and unsettled, which then drives the spiral to continue. Nothing happens in a vacuum. Some of the posting of the good stuff I see from others, I suspect is also driven by the need to be ‘seen’ to be enough. Thus we all stay on the carousel and it spins again.

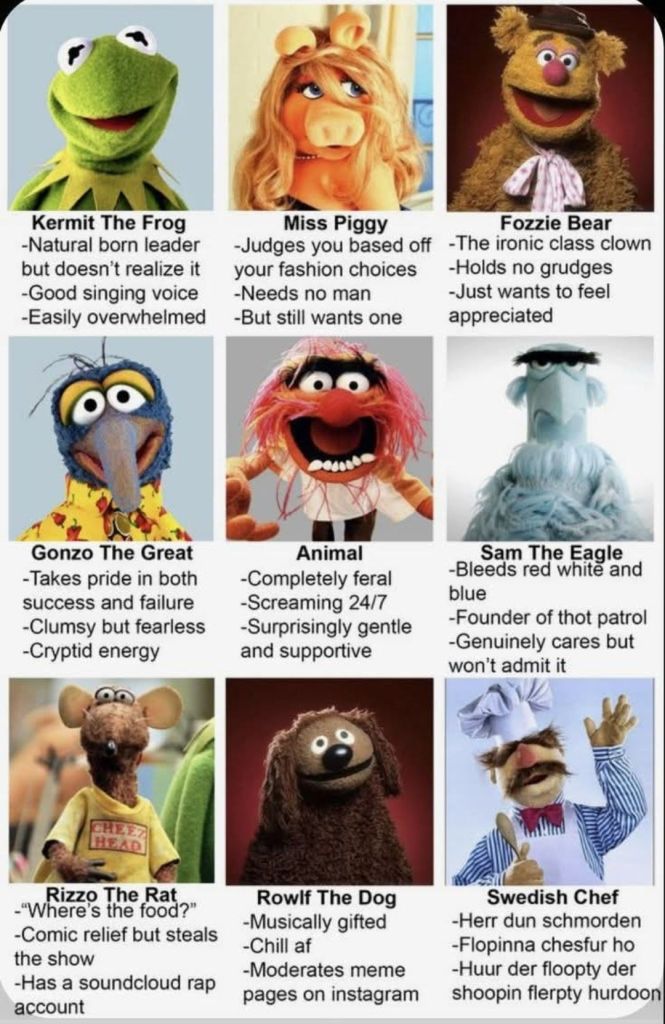

Portrayal through a singular lens

All posting on social media is biased, I’m not saying it’s not. What I am saying is that because LinkedIn is a platform that is basically set up as CV sharing, there is a string tendency to only share things that would be seen as CV candy. This understandably removes the balance of some posting that is undertaken on other platforms. I don’t see a lot of posts about people, the focus tends to be on events and milestones, and those events and milestones are almost always achievements, rarely do you see failures. It’s a world that feels, to me right now, that functions on toxic positivity. Once you become more aware of that posting bias it is probably easier to navigate, but as someone who wasn’t paying enough attention to notice the drift, I also wasn’t looking out for the impacts.

Everything is polished for public consumption

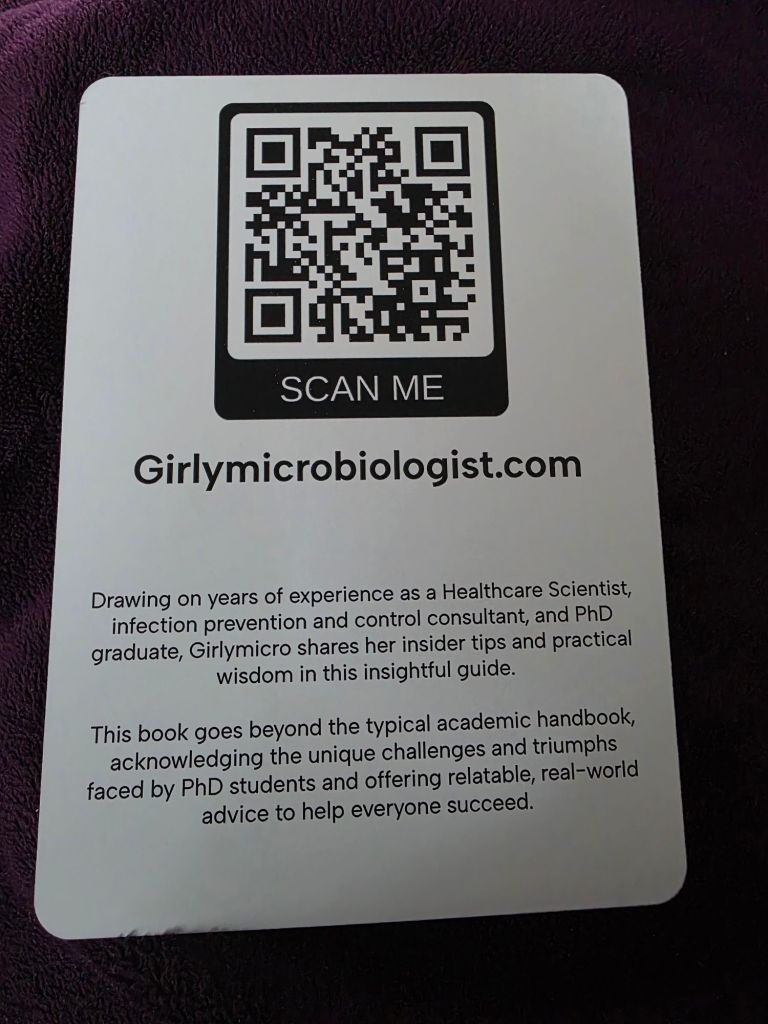

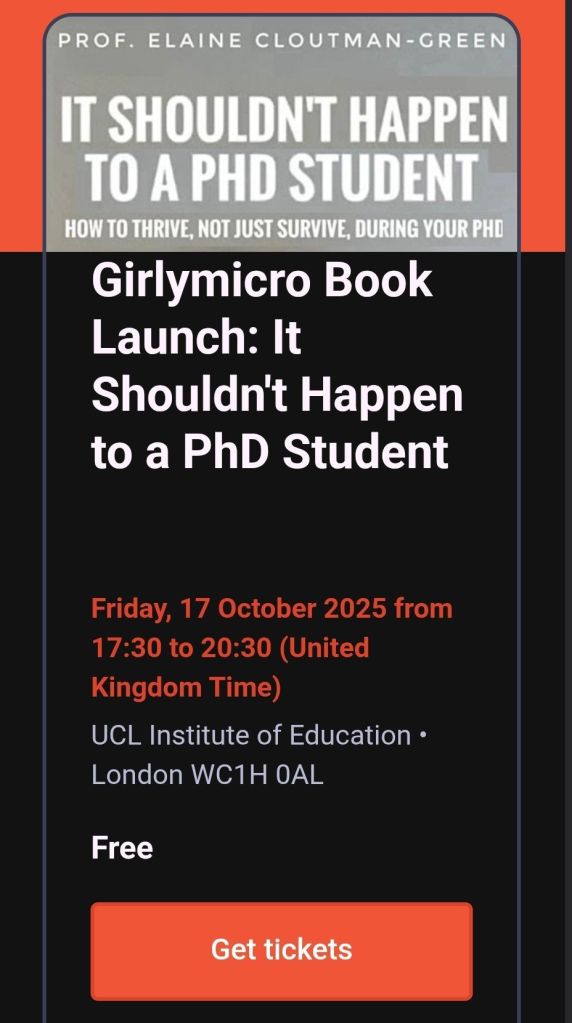

Due to this positivity, and I suspect in response to the tone of posts that are generally shared, everything is not just positive but dressed in a way to support branding. As someone who is known by more people as Girlymicro these days than Elaine I am in no way averse to people having a personal brand, I think it’s the world we now live in, but I think it’s the nature of that branding can be challenging. Branding that is all about surface or positivity does not feel, to me, that it can also be authentic.

It feels like it’s tick boxing, and worse than that, deliberately manipulating perceptions to cause us to be drawn into some form of unwinnable race where everyone is perceived as winning, but in reality we’re all drowning and not forming the real connections that could throw us a life line. I’m not talking about this at a person based level, but at a platform level. I just think it’s easy to get caught up without even realising, and to think that everything you are seeing is an accurate portrayal of the reality without undertaking the necessary sense checking on what is in front of you.

About perceptions rather than dialogue

One of the biggest changes that this type of posting leads to, is that it feels much more like shouting into a void. It’s about putting success out there, rather than leading to greater dialogue, or focusing on connection. Although it feels straight forward to gain a larger and larger following, I’m not sure how well I could say I know most of that following, outside of the ones that I also know in real life. This is in contrast to how I used to feel about Twitter, where I had connections that I formed and felt like I got to know really well, who I never met in person. Everything feels more superficial, although I have to say there are a few exceptions to this, it is far from universal.

Don’t get me wrong, there are benefits to forming these larger networks, but as Dunbar says, you can only maintain deeper connections with a small number of these contacts without deeper dialogue. These networks maintain a purpose, just not the same one that I originally felt that they would have. They are less about support and more about linkage for the purpose of opportunity sharing. Valuable, but different.

Being different is not a risk free strategy

The other big challenge, which I’m only just now getting my head around, is that LinkedIn is always fundamentally linked with my job. My job title and employer are front and centre on my profile. I have always tried to maintain my social media separate from my work. There is a reason every blog post finishes with ‘All opinions in this blog are my own’. They are my thoughts, my opinions. This is an important separation for me, and yet this separation isn’t easy to achieve now this platform switch has occurred. Now, don’t get me wrong, it’s not like I ever want to post things that are unprofessional, I don’t think that I post things that will impact my role, but I also have always appreciated the voice that independence allows me.

It is also true that, in a world where your posts are always linked to your CV, that posting outside of the norm could have an impact but not in the way that I would hope. It could be that posting holistically could be perceived as weakness and failure, rather than growth and learning. I have also encountered a few instances recently where personal opinions have landed on professional pages, because profiles were being utilised similar to twitter, which led to confusion of aims and muddying of the terms of reference for those pages. This has negatively impacted not just the page, but the person and project linked to it. There is a possibility, therefore, that getting this wrong is not a risk free challenge.

I am more than my job

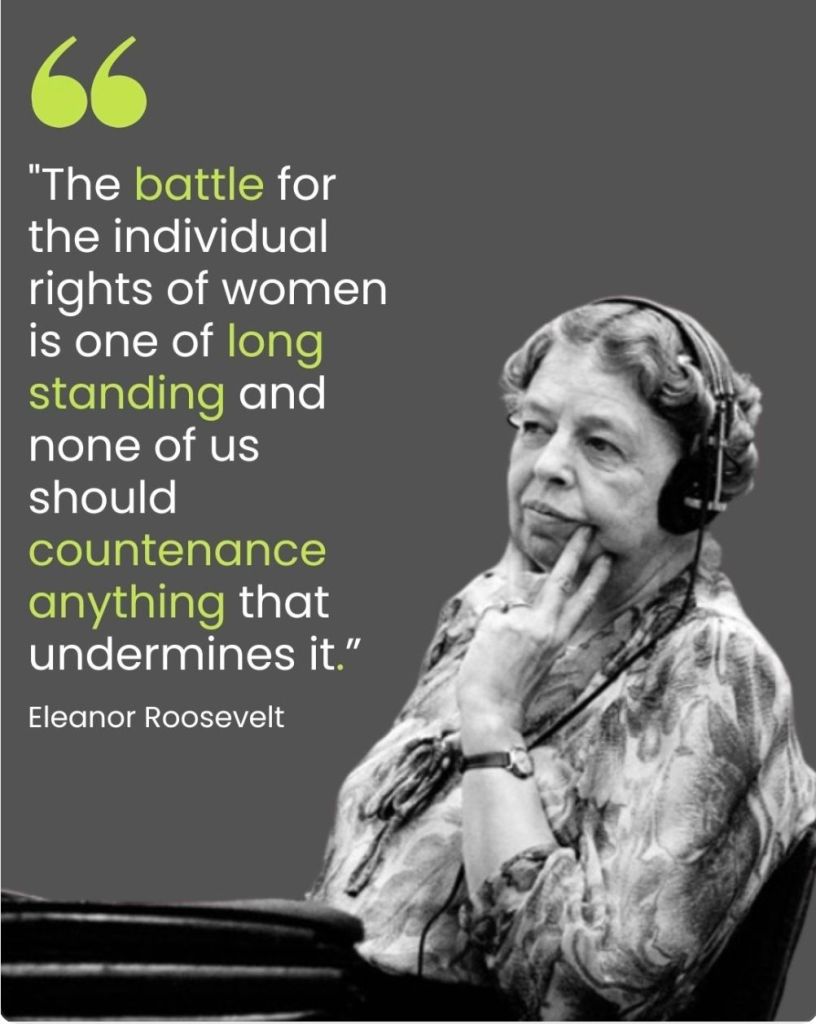

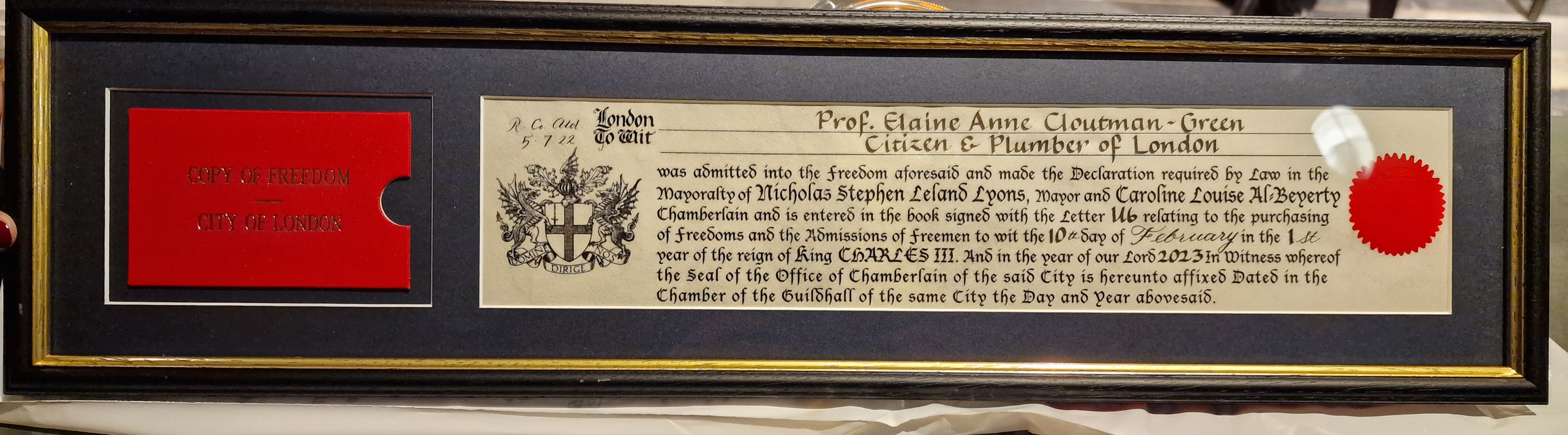

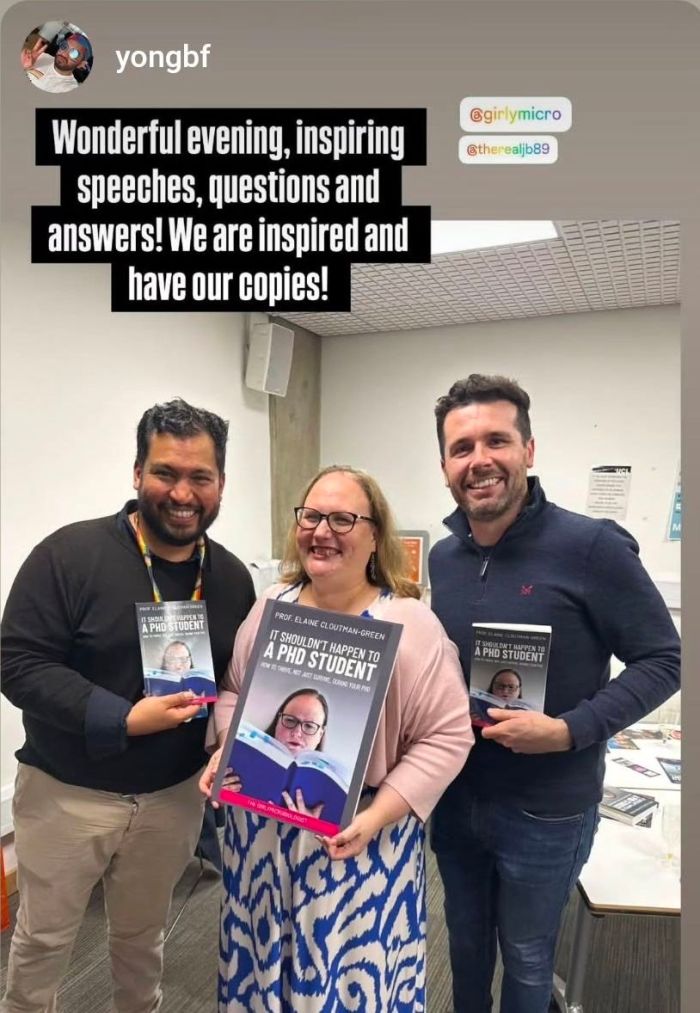

As profiles are linked so tightly to roles, it is also no surprise that the sharing and posting tends to be much more job orientated. The thing is, and I know this may shock you, I am much more than my job. I have interests and experiences that exist outside of my role, many of which I have shared across other platforms as I think it is so important for public engagement that people see who scientists are outside of the day job. People talk about the fact that you can’t be what you can’t see, and that isn’t just about the role. It’s about seeing that people like you occupy those roles. In my case, it’s about seeing that someone who didn’t go to private school, someone who didn’t always achieve academic success, someone with chronic illness, and who isn’t only interested in intellectual pursuits, can still succeed. By only posting about the role, we miss out on the fact that success means different things to different people, and not all of that is about the job. It limits the success that we share, and I’m not sure that that is a beneficial thing for those that aim to follow us.

Failure is learning

Another danger linked to only sharing successes is that the journey from point A to point B appears straight forward from the outside. This can mean that those attempting to follow a similar pathway can end up feeling like failures when they encounter a route that is less straight forward. It could mean that they give up because they lose confidence in their ability to complete the journey, when the journey may have been that difficult for others, they just aren’t talking about it. Rather than raising others up therefore, it can, as an unwitting consequence, result in discouraging others from following.

The other thing to note here is that I have learnt so much more from my failures than from my successes. My failures have taught me about who I really am, what really matters to me, what drives me, as well as how to do things better in the future. No matter how challenging, they have made me both better at my job and better as a human being. By not sharing our failures, it means they are almost seen as an embarrassment, when far from a source of shame, in many ways mine are a source of pride. Without them I wouldn’t have achieved, and so I think that learning is more worthy of discussion than any of my tick box moments.

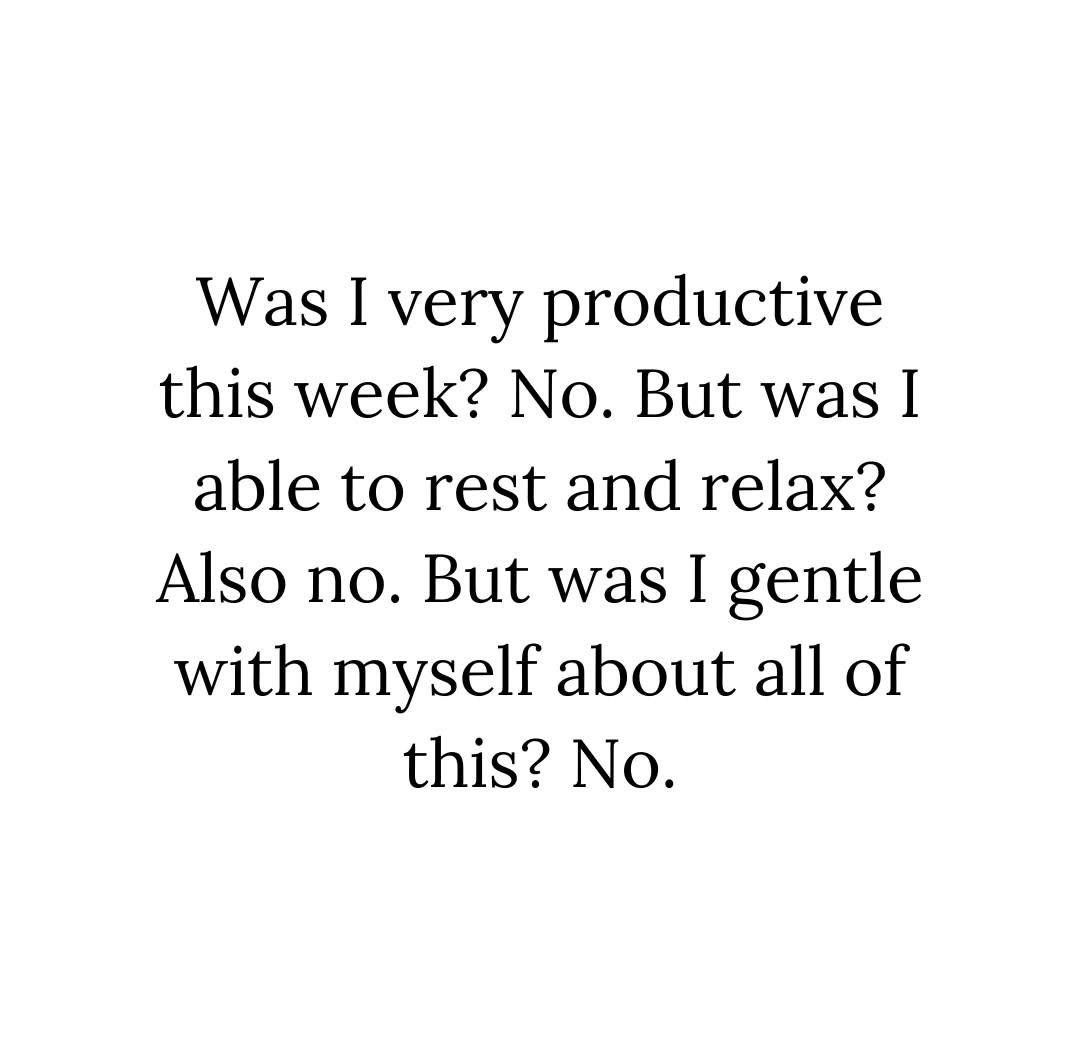

Rest isn’t failure

I have always struggled with workaholic tendencies. The need to work harder in order to feel like I’m keeping up and the resulting abandonment of self care. I’ve had to work really hard to attempt to put boundaries in place in order to maintain both my physical and mental health. I have a tendency to feel like I’m falling behind and that I achieve little in comparison to others. A lot of this is seated in having had to fight to keep up my whole life, whilst managing being unwell. I know that this is not anyone else’s problem, this is very much a me thing, that I am aware of and need to counter. I do however, miss the parts of twitter where we would celebrate rest time with others. Liking posts where people talked about what they were reading, going for drinks with friends, cooking, and spending time not being on the productivity treadmill. Now that success is re-focused on productivity I find it harder to remember that resting is not failure. I need to remember that rest is productive in it’s own way, and that my life is should not, and cannot, always be measured by how productive I am against a single given matrix. I miss seeing what people enjoyed doing outside of their role productive spaces.

Remembering that I’m running my own race

That has all been a lot about what I miss and what I’ve found challenging, but what am I doing about it now I’ve had some time to think? Well, first I am looking at LinkedIn a little less, and when I access it I’m acknowledging the success of others but trying to not get overwhelmed by what I’m seeing. I love cheer leading others on, but I need to find a balance. I’m learning to love Instagram a little more, not that I really understand that either, but it means I get to still see sides of people that are about rest and joy, not just a CV (I’m Girlymicro there if you want to look me up).

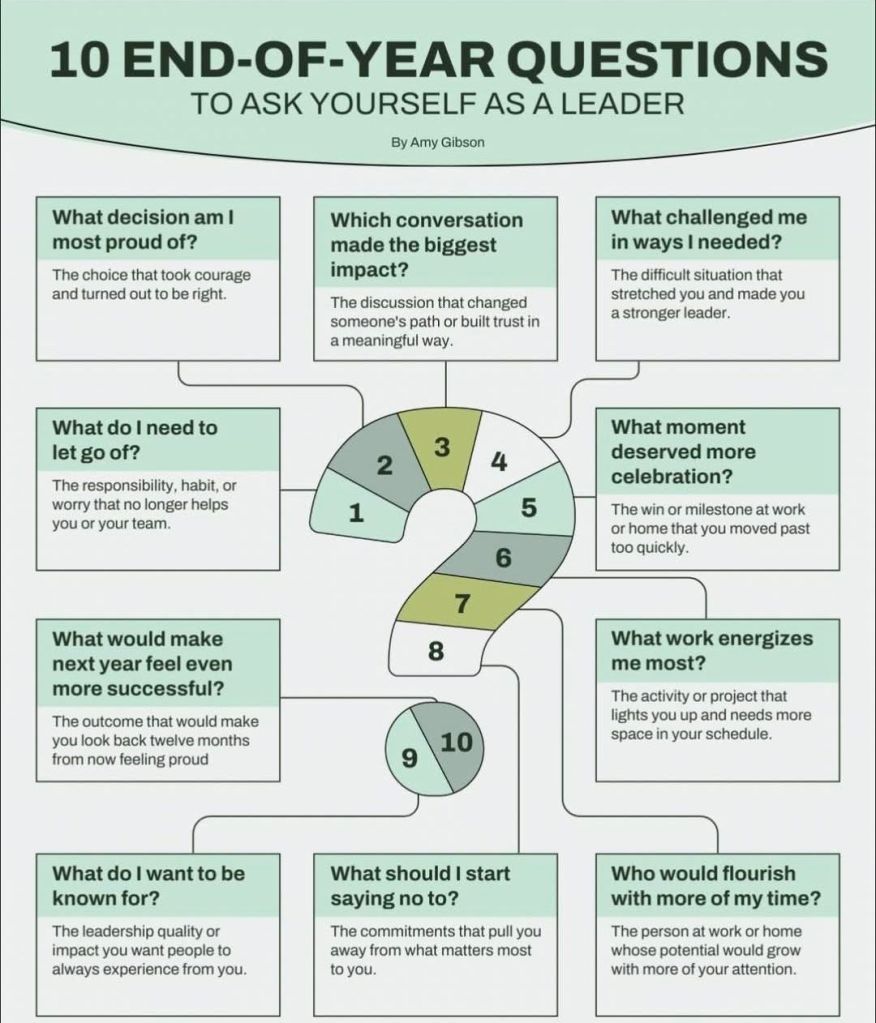

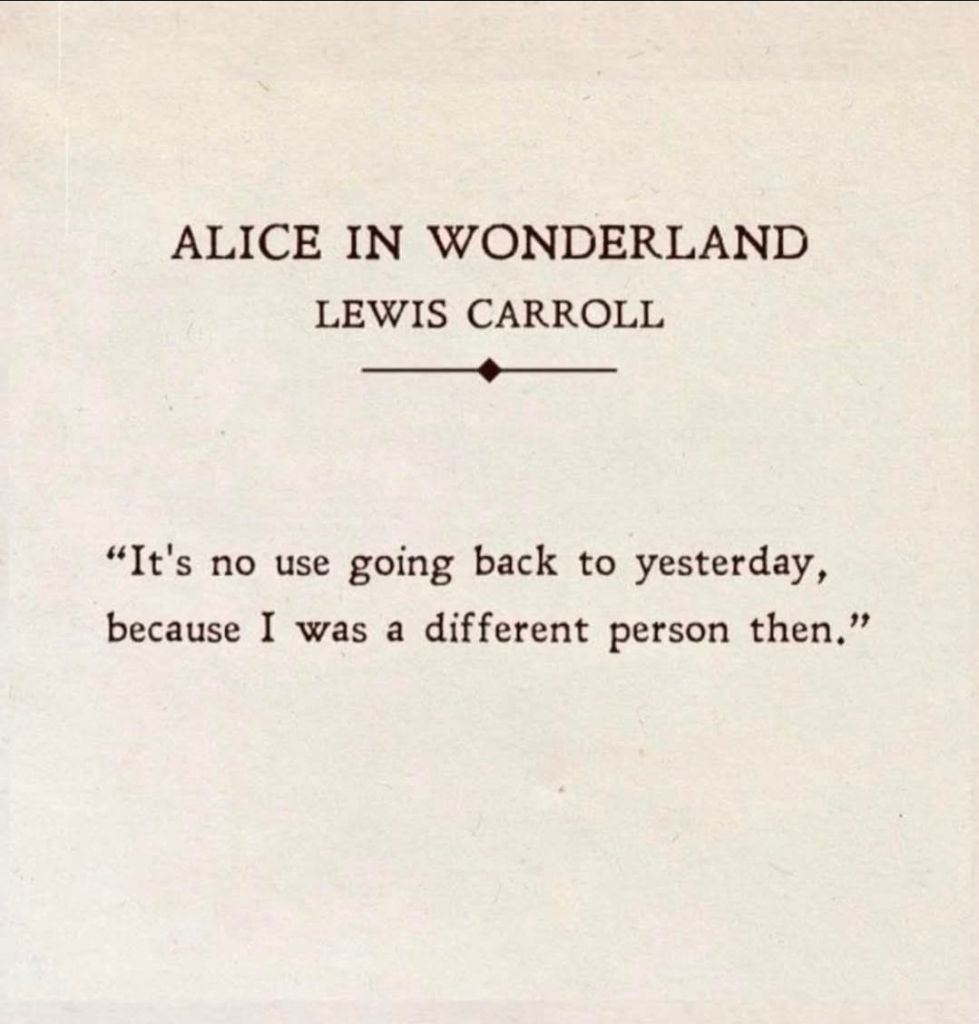

The biggest thing however, is that I now understand my responses to what I am seeing, and so instead of self flagellation, I am able to remind myself that I am just running my own race. I am pleased for others, but I am intent to only bench mark against myself. What do I want to achieve? What can I do this year that I could not do last year? Where is my learning? What am I doing to become a better scientist and human being? Worrying and giving head space to the self doubt just makes me anxious and achieves little, so I need to actively focus on taking my next steps uninfluenced by others.

Bringing authenticity back

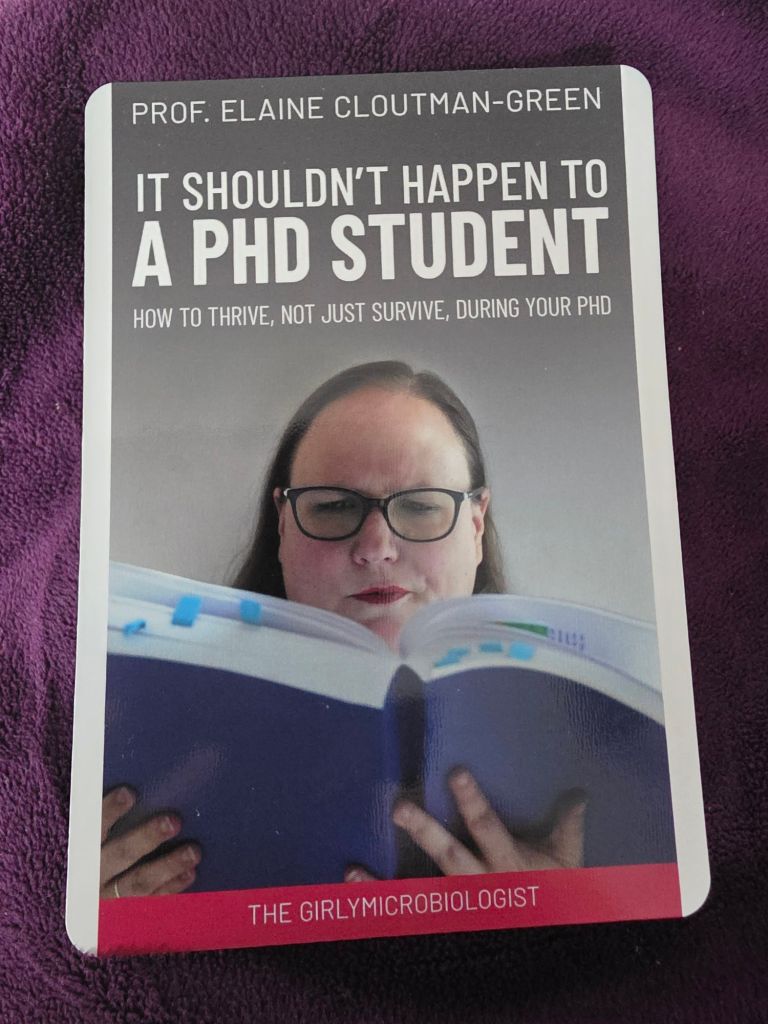

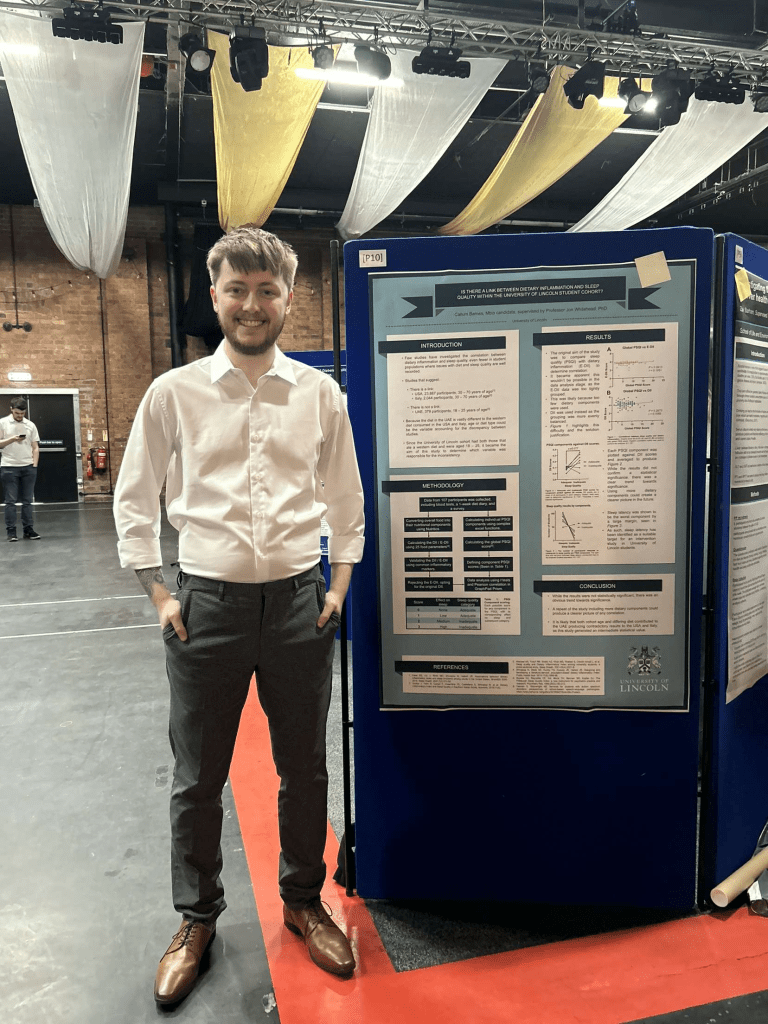

As well as changing my approach when reading others peoples posts, I am also going to deliberately take some risks and makes changes in some of what I post. Instead of only sharing the shiny bits, I am going to share posts like this but also ones like the one below, that don’t disguise the fact that I find some days, some challenges, some moments, just hard. I think being aware that the platforms we use have different unwritten rules is the first step to understanding what is possible, and I am happy to push the boundaries of that, without acting like it is something it is not. LinkedIn has a lot of benefits, so I plan to embrace it for what it is, rather than pretending it is something it isn’t, but I intend to do that by sharing more of my authentic self when appropriate.

Reflecting on the dangers of comparison

This whole process has reminded me of how dangerous it can be to compare ourselves to others. There are many benefits to using others to inspire us, to see and understand the possible. Maintaining these benefits without letting comparison start to limit or impact our sense of self is something that I think we all need to be aware of. This could just be because I’m a peri-menopausal 40 something who has lost a lot of her confidence after the pandemic, but the brain weasels are real, and being aware of triggers is an important part of stopping spirals before they begin. Knowing how much is enough, knowing my purpose, and what I am aspiring to achieve, are important aspects to keeping me centered and in a good place. I’m focused on the vision, not the comparison right now.

Loving my imperfect self

Most important of all, I am reminding myself that I am enough. So what if I don’t publish as much as I’d like to. So what if I haven’t found time to write the grant applications I’d wish. So what if I don’t feel like I’m always impactful enough, or accepted for my expertise without constantly fighting to be visible. At the end of the day I come home to Mr Girlymicro who loves this flawed human for who she is. He loves me irrespective of my successes or failures. He loves me despite the fact that I fall flat on my face and throw food down myself on a regular basis. He loves and believes in me when I have no ability to do those things for myself. So I am taking a leaf out of his book and trying to see myself through his eyes. I am trying to love all of me and not place caveats upon that love. To know that my value is not based on what I’ve achieved, but who I have achieved it with and the relationships that got me there.

No matter what social media you use, or how you use it, always remember that if you can return to a place of true connectivity where you are seen and loved for all you are, it doesn’t matter how you are seen out there. You are always doing better than you perceive, and are almost inevitably loved more than you know. Keep the faith, and treat yourself as kindly as you would treat others in a similar boat.

All opinions in this blog are my own