This month is the start of a painful re-entry into normal life. Normal life in terms of work demands, normal life in terms of commuting and normal life in terms of getting back to not eating party food and leftovers for at least 50% of our meals. Now, mummy Girlymicro, Mr Girlymicro, and I have done our fair share of celebrating over the last few weeks, including eating out at large catered events and throwing our own parties for friends. Clinically, norovirus is now giving us its cyclical peak, and there was also a lot of food related outbreak news over the holidays. I thought, therefore, that I would start this years IPC related posts with one on foodborne outbreaks and the kinds of organisms involved.

Food related sickness and outbreaks can be caused by a number of different microorganisms and through a few different routes. The two main routes are infection and intoxication, and these are related to the organisms that tend to be the causative agents. The foods that are linked to these routes are also different, and if investigating can give you an idea of what you might be looking for, especially when combined with presentation, both in terms of clinical symptoms and speed.

Infection vs intoxication

Intoxication based food poisoning is usually linked to rapid onset symptoms following the ingestion of the food i.e. a matter of hours. This is because the symptoms aren’t related to an infection based process, where symptoms are linked to the invasion and replication process of the organism. There are two main types of toxins, heat stable and heat labile toxins. Heat stable toxins can be problematic, as once present in food these cannot be removed purely by re-heating to an appropriate temperature. Heat stable toxins, such as those produced by Bacillus cereus, are produced when the bacteria are present, hitting the right temperatures then kills the bacteria but the toxins remain. This process can be exacerbated when foods are not rapidly chilled or are left at a temperature where the bacteria could grown, there is therefore a prolonged period when toxins could be produced. Toxin related food poisoning (intoxication) can be caused by both bacteria and fungi.

Infection based food poisoning is linked to the ingestion of the organism itself, and presentations are therefore usually delayed as the organism needs to infect the gut mucosa. Many organisms that produce toxins can also cause infection related symptoms if present in high enough loads, and if suitable temperatures for bacterial kill are not met. Infection based food poisoning can be due to viruses, such as norovirus, parasites, such as E. histolytica, as well as bacteria, and the risks are often related to food hygiene efficiency as well as production factors.

Patient management

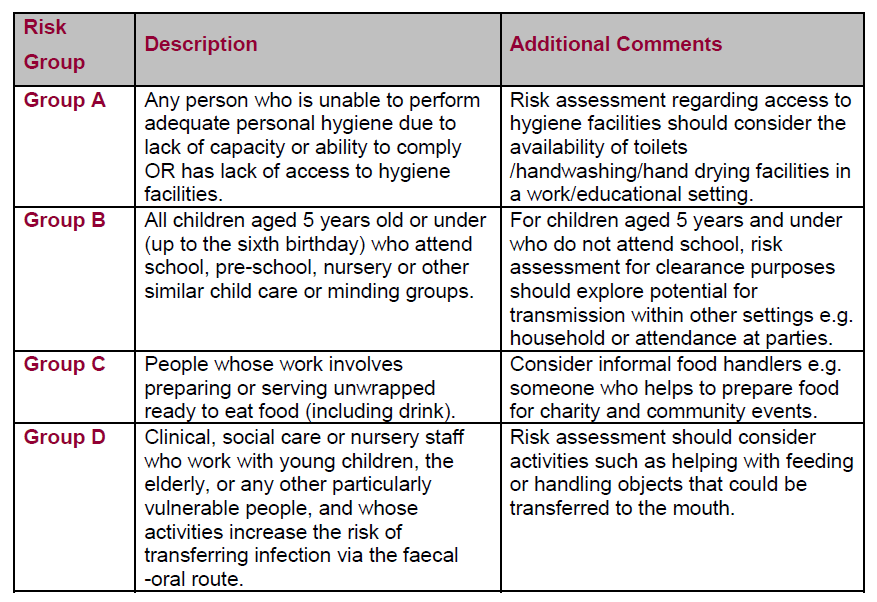

Most food related illness self resolves and management is mainly focussed on maintaining hydration and electrolyte balance. There is usually a requirement to undertake a minimum isolation period of 48 hours post symptoms in order to prevent any ongoing risk of person to person transmission, even if the original acquisition is thought to be via a food related source. Isolation may need to be prolonged in relation to certain groups because of the risk of ongoing to spread to others, either through personal hygiene awareness or through work based activity.

Recommendations for the Public Health Management of Gastrointestinal Infections 2019: Principles and Practice has a lot more detail on the main organisms associated with foodborne illnesses and some of these requirements for isolation. I’ve attached a copy below, but the link is also here in case it’s useful.

If symptoms continue for period of a week or are especially severe it may be necessary to take samples in order to identify a causative organism in order to support patient management. When taking a patient history it’s important to capture any patient specific risk factors (see below section on risk groups), travel history, recent event attendance history and details of hobbies (such as preserving) that may impact of food ingestion patterns. Additional individual management options can include antimicrobials (antiparasitic or antibacterial) and for non-bloody diarrhoea without fever antidiarrheal agents.

How do these organisms get into food?

Organisms can get into food from numerous sources. They can be present in the environment in which the food comes from, such as manure that is used to fertilise salad plants can contain organisms, like E. coli, even more so if human waste is used. Food, such as oysters, can be contaminated as part of their life cycle as filter feeders if they are growing in an environment where they are exposed to animal or human waste, and so can harbour organisms like norovirus and become highly loaded. Food can also become contaminated as part of the production or manufacturing process, contaminated from other items that are produced in the same facility, contaminated from the processes, such as the water or preservatives utilised, or from failures in the preservation process that would normally have removed organisms that are naturally present linked to food.

Organisms can also come from the humans involved in the process. Those manufacturing or handling the food may be carrying or infected with organisms, whether symptomatic or not. A Staphylococcus aureus colonised person making sandwiches may contaminated the food they are making. An asymptomatic norovirus infected canteen worker could expose those being served food by unwittingly contaminating food and/or serving implements. In the case of bacteria, low level contamination from those producing the food may then be able to grow up to levels where ingestion results in symptoms if the processes are not well enough controlled.

Food processing and manufacturing

Most food preserving techniques aim to ensure that if contamination occurs during production or manufacturing it is not able to replicate to the point where the organism would cause symptoms in those who ingest them. Many preserving techniques aim to control organism survival or replication/loading via either temperature, cell lysis/resource availability or both. There are two main groups of techniques, either physical or chemical.

Some of these processes are more prone to risk of failure than others, both depending on the process and where is it being undertaken. When undertaken in food manufacturing, these techniques are usually undertaken under highly controlled conditions using the HACCP process in order to manage some of this risk variance:

Food preparation in the home

Obviously, none of us are following HACCP processes when we are preparing food at home, that doesn’t mean that there isn’t any risk to home cooking. One of the hazards linked to cooking at home can be the home environment itself. I’m still aware of people who wash out chicken or turkey cavities in their kitchen sink, unaware of the droplets that are produced and how they can then deposit on other surfaces, which are now contaminated whilst appearing visibly clean. Other hazards can link to the fact that most of us don’t have access to rapid (blast) cooling, and therefore when cooking big batches of food and putting in the fridge, the cooling process may not be fast enough to prevent bacterial growth. Also, in terms of equipment, I work in IPC and I’m a bit of a control freak so I possess things like meat thermometers, in order to ensure that meat has reached appropriate safe temperatures. I am aware that not everyone lives in this particular world, and so may not have some of these pieces of kit lying around.

Most of the time if you end up preparing food less well at home the consequences are non-ideal but not massively serious, however, if you have an ‘at risk’ member of your household or visiting then it becomes more important to focus on controlling these risk, both through the food that is brought and how it is prepared.

Food preparation (catering)

We’ve already talked a little about the HACCP processes that are put in place to control risk in formal settings. Catering can be a tricky area of risk, even if undertaken by professionals. It is one thing to undertake catering in your restaurant or a space you work in all the time. Catering however, is often undertaken in sites that are not the ‘home’ of either the professional or the average person. Catering equipment can be hired to serve food in church halls, for weddings or other special events. It can also be undertaken on beaches, in forests and other remote locations with variable levels of power to support refrigeration. This can mean that control processes, such temperature control, are undertaken in atypical ways, such as temperature control using ice packs, which will have variable efficiency depending on external factors, such as ambient temperature.

Home catering for parties also brings risks. I love to throw an afternoon tea party for charity, but that means that I am suddenly trying to put waaaaaay more in the fridge than I normally would. Food may be out on a table for a number of hours. Some of the food may also be high risk, such as cheese or smoked fish, and it will be next to less high risk foods. Also, if you are not used to prepping food for large groups, you may inadvertently increase risks by the order in which food it prepped. That is without the risk of people bringing food to contribute to yours which you don’t know the origins of, or people picking up food with fingers and therefore increasing risk of spread if they have anything onboard.

Food storage

Once all of that catering is done, you are then left with a decision, what do you do with all the food that is left? Do you then try and shove it all in your fridge or freezer? Do you give it people to take home in Tupperware pots? How much have you taken into account the length of time that food has been non-temperature controlled? What does that do to the use by? Is everyone aware of any re-heating requirements or the dangers irrespective of re-heating of intoxication?

Issues with food storage are true not just for party catering, but also for batch cooking, something a lot of us are doing more and more of now the weather is colder and because food it more expensive. Foods like stews and rice dishes, which are high risk for intoxication, are also the kinds of foods that fulfil a lot of batch cooking requirements. It is really important to bear these risks in mind, ensuring rapid cooling and that temperature is monitored appropriately.

This also extends to ensuring that even dry goods are stored appropriately. We’ve all been there when we’ve found the pack of spice that 15 years old. Spices, canned goods and other preserved food have been identified as the source of outbreaks, and even when originally in good condition can become a risk if not well maintained, such as dented cans or if moisture has gotten into packets.

What kind of incidences are we talking about?

Over the Christmas period there have been two well publicised food related outbreaks, one linked to E. coli in cheese and one linked Cronobacter sakazakii (previously Enterobacter sakazakii) in infant formula.

BBC News – One dead after E. coli outbreak linked to cheese

This outbreak was linked to the presence of STEC toxin producing strain of E. coli. This leads to an intoxication that can impact of kidney function. Although not stated, elsewhere it was reported that the cheese may have been made from unpasteurised milk, removing one of the stages used to control organism risk in food production.

Advice for individuals from UKHSA included:

“Washing your hands with soap and warm water and using bleach-based products to clean surfaces will help stop infections from spreading. Don’t prepare food for others if you have symptoms or for 48 hours after symptoms stop.

“Do not return to work or school once term restarts until 48 hours after your symptoms have stopped.”

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-67840758

The other recent recall was linked to possible contamination of infant formula detected at manufacturing. Formula feed outbreaks linked to Cronobacter sakazakii have been noted in the past, with a large outbreak in France being the last large scale event. Infection does not just lead to GI symptoms but is associated in some patients with presentations such as blood stream infection and/or meningitis.

The formula included in this recall is mostly used in healthcare or is prescribed to individuals. This makes it critical as it is likely to have been given to an ‘at risk’ population. Milk related contamination is particularly challenging as heating impacts the nutritional content of the milk and so use of thermal risk reduction is not straight forward. Some hospitals, such as the one where I work, undertake an additional step, pasteurisation, for any formula feeds due to be given to high risk infants because of this well acknowledged risk in order to support infection risk reduction.

BBC News – Baby formula recalled over bacteria contamination fears

October 2021 Frontiers in Microbiology 12

There are obviously multiple examples every year of foodborne risks linked to contamination at source or HACCP failure, but these are the ones that have been most recently featured in the national press.

Are any groups at higher risk?

Although food related infection or intoxication can impact anyone, certain groups are more at risk of significant symptoms requiring treatment or are more at risk linked to certain organisms in terms of presentation. These groups are your very young, very old, the immunosuppressed and pregnant women. The very young and very old are more likely to need support linked to dehydration, and all 4 groups are likely to be less able to mount immune responses to invasive infection. The immunosuppressed and pregnant women have specific guidance linked to avoiding high-risk food groups because of severity of impact if infection occurs.

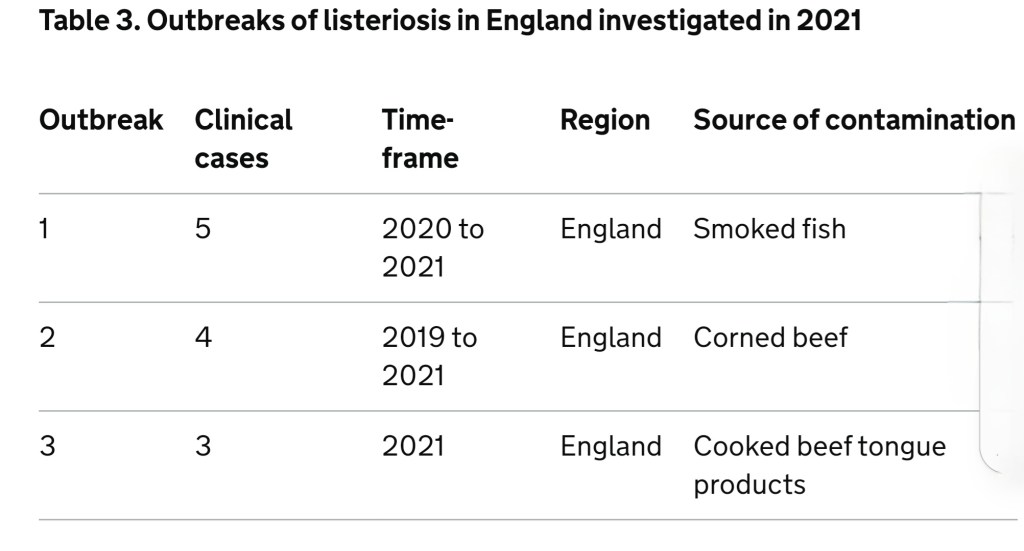

One particular organism linked with significant infection risk for pregnant women and the immunosuppressed is Listeria monocytogenes.

Listeria crosses the gut wall at locations known as Peyer’s patches, and from there invades lymph nodes and blood. Once in the bloodstream, it can progress to cause meningitis/encephalitis by infecting the brain. In pregnant women it can also cross over into the placenta, where it can cause infection in the foetus/unborn child. Foodborne listeria outbreaks have been associated with a wide variety of foods, but are often linked to preserved foods and cheese.

How do we investigate foodborne outbreaks?

There are a number of stages to investigating foodborne outbreaks. Initially, there will need to be some sort of flag to suggest an outbreak event. This is usually a number of people attending GPs or A&E linked to a single event, an uptick in samples positive for a specific organisms that is noted through lab reporting, or any cases of specific reportable organisms which will then get followed up.

Depending on the circumstances, a combination of the following steps will be undertaken:

- Patient questionnaire (case)

- Questionnaire of those who attended the same event but did not get sick (control)

- Sampling and microbiological testing of possible implicated food, if still available

- Sampling of the production environment, such as factories or restaurant kitchens

Investigation needs to be undertaken to identify the target food or batch as most production facilities will make more than one kind of food and will have multiple batches. If the outbreak is linked to a specific event, multiple types of party or other food is likely to have been available. Getting more information about what those who got sick ate vs the others enables you to narrow down what the culprit might be.

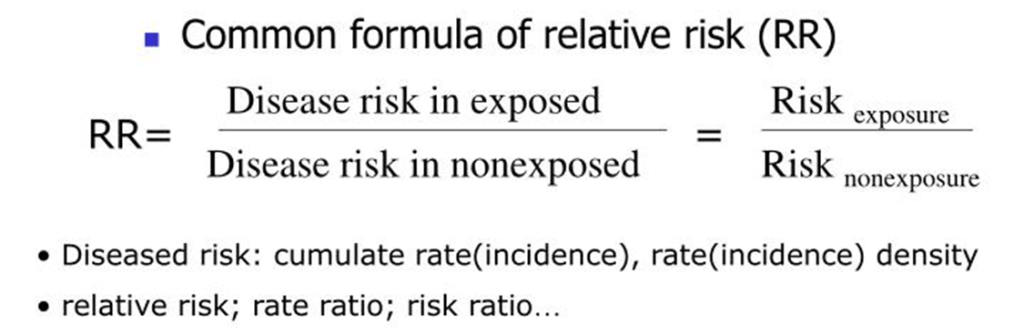

Once you have your questionnaires, it’s time for a little bit of stats. This enables you to calculate something called the relative risk for the cohort. The cohort being all those people who were at the same event, ate at the same restaurant, brought food from the same factory etc. This will include those who became unwell and those who did not. For each type of food or batch you can calculate a ratio of the risk of disease (infection/intoxication) in people who have been exposed (ate that food) compared to those unexposed (decided that food was not for them).

You then get a list of risks for different food types eaten. So if the following food was available at our event you can then undertake the calculation:

- pigs in blankets

- mini fish and chips

- turkey and stuffing roulade

- mini pavlova (with cream)

- cheese pinwheels

If the number if >1 then it indicates and increased risk, if RR = 1 then it doesn’t impact on risk, and if RR <1 then there is a risk reduction. So in the case of our party food:

- pigs in blankets RR = 1

- mini fish and chips = 0.98

- turkey and stuffing roulade = 1.73

- mini pavlova (with cream) = 1.1

- cheese pinwheels = 0.99

In conclusion………the turkey probably did it!

I hope that’s helpful, I know there’s loads more that could be covered, and if you are interested in anything in particular drop me a comment and I’ll see if I can post a follow up. The main take away is that there are multiple organisms that can cause foodborne infection/intoxication, and whether it’s home or out and about we can all be impacted. For most of us, it’s an unpleasant but low consequence event, but there are are people and populations where the outcomes can be much more severe. So, if you’re ever asked to complete a questionnaire please do so, and don’t ignore those news articles that tell you to throw an item away as it’s not a risk worth taking.

All opinions in this blog are my own