It’s the Easter weekend and I haven’t posted a book review in forever, so I thought I would post a review of something that not only I think all scientists should read, as a tale of when science goes wrong, but also because it’s been dramatised and so you could also spend some of your weekend enjoying it in multiple media forms.

I didn’t really know much about the Theranos company before I read this book. I had seen a couple of news articles and video clips of Elizabeth Holmes, but I don’t think it made quite the same coverage in the UK as in the states. I do remember a video of her talking about being able to do several hundred tests from a drop of blood and rolling my eyes and being dismissive as it struck me as scientific nonsense. I didn’t realise this was a system that had been rolled out for actual patient testing and as the basis for clinical decision-making, which to me is incomprehensible. I’m getting ahead of myself however, here is what the book is about.

Bad blood is written by the journalist John Carreyrou, who broke the story at the Wall Street Journal. It is a chronological re-telling of the rise and eventual fall of the Theranos company and its founder, Elizabeth Holmes. It is based on interviews and fact finding that were collected for the articles and runs up until the start of criminal prosecutions.

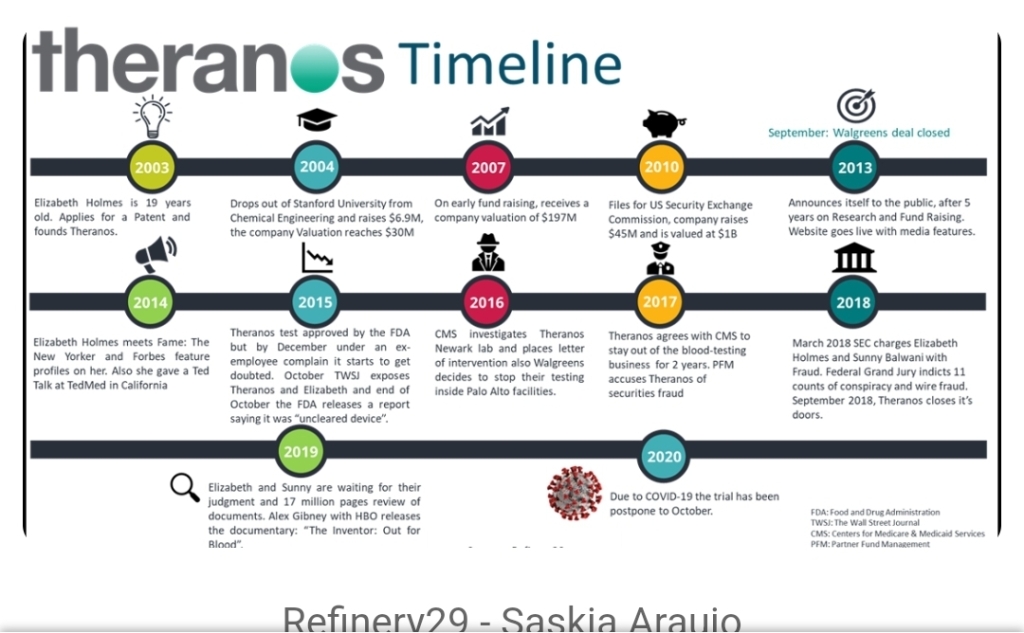

Elizabeth Holmes is a self-proclaimed Stanford dropout who left university to pursue a bio tech start-up. She claimed to be terrified of needles, so established a company that would enable the avoidance of venopuncture blood draws by using point of care testing using a finger prick to provide the same level of diagnostic information. The end vision sold to investors was that this could all be done by a small microwave sized machine that could, eventually, be sold for home use as a form of self monitoring. The platform was rolled out into patient use at Walgreens chemists, as the first step in a national roll out. Testing patient samples and providing clinical results in Phoenix, Arizona. Interestingly, to me, as this was a private biotech company, there appears to have been little to no oversight of this diagnostic roll out, despite producing a medical device.

The book covers how investment was attracted and rapid growth attained because of the strength of this vision and the charisma of the woman selling it. It also covers how, despite scientists not being able to deliver this vision, it continued to be sold and how the very negative company culture allowed this to happen. All company employees were made to sign non-disclosure agreements, they were prevented from talking outside their teams, their emails were monitored, and threats of legal action appear to have been common. This meant that many of those working on development were unaware of the significant flaws with what was being sold, and those that were and considered or tried to whistle blow were taken down legal routes, where Theranos had considerable more financial capability to attain a positive outcome.

This was all compounded by a lack of oversight and, as there were no regulatory affairs staff employed, allowed governance processes to be manipulated. The company had two laboratories, one to develop their new technology known as Normandy, and one which was disclosed and Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) accredited which containing more standard technology platforms known as Jurassic Park.

Eventually, after the death by suicide of one of the employees and increasing press coverage seen by external scientists who questioned how this was possible, as well as clinical alarm bells, enough momentum was gained to put together a story that shone the light on why this approach was disastrous for the patients who were relying on it.

The story is already available in many different forms, including a TV series that is currently available BBC iPlayer and Disney+

Listening to the audio book of this book whilst I write this blog post it makes me think that are a lot of points that shock me as a English scientist working in such a highly regulated environment, both for NHS services but also for me as a state registered individual. It has also made me reflect on how crucial support for escalation and whistle blowing is to ensure that scenarios also get flagged when those services are not providing the quality of service required. I’ve briefly outlined some of my reflections below:

Governance

I spend a lot of time in governance meetings, both local and national. I even sit on a number of grant, research and ethics panels. I don’t think I’ve ever encountered the kind of lack of governance and accountability described in this book. That said, I’ve never worked in private industry or a start up. Just going through this book has made me have a new recognition for how important it is that boards and other oversight structures, ask the difficult questions and undertake constructive challenge in order to identify problems early and reduce risk.

Responding to No

At every stage in this re-telling smart people tried to raise concerns. When concerns were raised those people raising them were either isolated or asked to leave. Those who played the game and did not rock the boat were promoted, ending up in a scenario where the entire of the senior leadership were either the ones who didn’t want to hear or were people that didn’t want to challenge. In other words Elizabeth deliberately surrounded herself with yes men and thus created her own echo chamber. You can see, to an extent, how this can happen in other settings and where unacknowledged risk could therefore be introduced, and so ensuring that challenge is encouraged and not victimised is key to success.

Female leadership

Being a female leader is challenging, being a female leader in the technology and science sectors is both challenging and unusual. I can’t help thinking when reading this book how much of a back lash will occur and impact other female innovators. Elizabeth was heralded as unique and special for being a female in this area, I feel it’s likely that her actions have significantly set back other women in this space trying to make room for themselves. In addition to the patient harm caused, this is one of the things that upsets me the most.

Authentic leadership

To succeed, Elizabeth crafted a new image of herself. She changed the way she dressed to look more like Steve Jobs, whom she admired. She even changed her voice to use a lower octave, as she felt it made her more unique, memorable and aided success. I’m rather struck by the fact that she changed the way she dressed to look and even sound more like her male compatriots. If she changed these external factors, I can’t help but think what else she changed, and how much she went against all the principles of authentic leadership. She shared little of the real her, and I wonder how much that facade enabled her to distance herself from the reality of what she was doing. For me, it’s a reminder of why authentic leadership is so important, to put yourself out there and also to be held to account, rather than introducing a facade which distances you from your actions.

Quality assurance

Quality assurance, ensuring you get the right result on the right patient in the right time frame, seems to have features little if at all in the Theranos story. They utilised out of date reagents, the way they undertook validation testing is like nothing I’ve ever encountered, and they topped it off by actually lying about how and where results were produced. It’s easy to think that we would never act in the same way, and I doubt any of us would to the same extent, but there are aspects of laboratory life which I think would be open to monitoring challenges. The expansion and use of home testing, and even point of care testing (POCT) presents a lot of quality control and assurance challenges. These tests are conducted outside of standard laboratory settings, often by individuals with less knowledge about the processes. How do we increase access whilst maintaining quality in these circumstances? I think it’s something many of us are wrestling with.

Research and innovation

Innovation has risk associated with it, research wouldn’t be research if there were not unknowns. The patient impacts of this work however have given me a chance to reflect on how import ethics and governance reviews are to controlling these risks. As the testing was not rolled out during a trial, there was no consenting of patients to those risks. The people who ran the institutions in which they were rolled out were also not informed that they were effectively partaking in a research experiment. This means that all those involved are less likely to engage in research based processes in the future, as trust has been broken, even if it were to happen with different more established individuals. Thus the behaviour of a few impacts us all, and therefore as scientists we have a responsibility to flag this bad behaviour as and when we see it.

Listening to the scientist in the room

The scientists in the room were not heard. The company was led by people who lacked technical skill. Rather than understanding their limitations, they actively denied any lack of knowledge. They therefore didn’t listen when those best placed tried to flag issues. There was also no route for whistle blowing, either to the board, or to external organisations, partly due to the NDAs and threats of litigation. As a leader, this has made me reflect on both how important it is to listen to those skilled individuals you have working for you, but also how much there needs to be processes in place that bypass me in the case of a need for escalation. No one is perfect, and it is so important that concerns are heard and acted upon.

Silos limit productivity and communication

One reason that Theranos not only manage to hide its failings, but also probably failed in the first place, was that everyone was kept in silos and isolated from each other. There were no multi-disciplinary collaborations, sharing was actively forbidden, and there were no cross department routes of communication. Everything was linear, up and down. This can easily be seen as a failing in other large institutions, not because of an active plan, but because we don’t encourage enough cross organisational working. Collaboration is key to innovation, trouble shooting, but also to fault finding and improvement. It takes effort to do well, but is worth investing the time and energy into for improved results.

Vision alone is not enough

Vision without follow through is always going to fail. Vision without working pragmatically on turning it into reality will not succeed. Once you move from vision into implementation or delivery, it cannot be enough that you alone own the vision. It has to be shared, it can no longer be owned by an individual. By sharing it, you also have to take onboard the input of those others, and if you cling to the original too tightly then you are setting it up to be a disappointment.

People are the ones who suffer

People were actively hurt by this poor use of science and innovation. The scientists themselves suffered when they tried to raise the alarm, emotionally and through litigation. Most of all though, the patients who placed their faith in a diagnostic that could never deliver suffered, either through over or under treatment. Because this tale occurred in the states, those failings also came with a financial burden, as well as a physical one. This book makes me so grateful for the NHS and our regulatory structure for the governance and protection it provides. Nothing is perfect, but an imperfect something is so so much better than the alternatives. I hope you find the book as eye opening as I did.

All opinions in this blog are my own