I am not a big Halloween girly, to be honest I can take it or leave it because I’m mostly excited about the build up to Christmas. That said, what I do love are movies and TV, and despite never being someone who can tolerate a lot of slasher or gore based horror movies, I love a good vampire movie.

A lot of this may be because I enjoy the world building and lore that seems to be more integral to vampire movies and series. This is because, although they share some of the same rules, depending on how the world is built they always need to explain which of the nuance comes into play in that particular setting. It felt fun this Halloween therefore, to write a blog post that talks about some of those tropes when vampirism is linked to infection, and how those rules compare to the real world.

Common vampire tropes to be aware of and to bear in mind as you read on:

- Experiencing pain or physical damage in relation to sunlight

- Needing to consume blood as a protein source

- Inability to eat or digest food other than blood

- Avoidance of animals

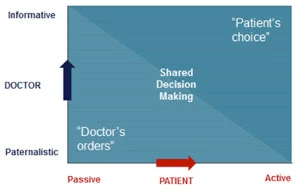

- Ability to influence humans to undertake acts that may be against their will

- Violent reactions to garlic

- Inability to see themselves in mirrors or via cameras

- Death only by beheading

- Death by wooden stakes

- Damage linked to holy water

- Aversion to signs of faith

- Aversion to alcohol or drug use

Not all of these are present in every piece of world building, hence why I find the variety of vampire mythos so interesting. The choice of which ones go together combined with different origin stories and creation processes enable a pretty large tapestry to be created from some similar thematic components.

Mystical, infections or something else?

The place to start I guess is by discussing whether all vampire world building includes infectious transmission? And the answer is a definitive no. Sometimes the way that the creation of new vampires works isn’t discussed. Sometimes the rules about the underlying process is unclear. That said, the fear of becoming something new is a frequently used trope for dramatic purposes and so the process by which a human is turned into or by which vampires exist is discussed pretty frequently as part of world building, and from what I can see there are three main routes:

- Mystical – some form of occult/magic/cause not routed in science

- Genetic – vampires are born and exist as a stand alone species

- Infection – transmission via blood or other infectious transfer, even if the agent is unclear or unspecified

Now, I’m not going to cover the mystical/magically as that’s not anything based in science and the science is what I’m here for. The other two, however, are often based (sometimes loosely) in science as they are often inspired by things that actually exist and so I’m going to talk about both of those in a bit more details.

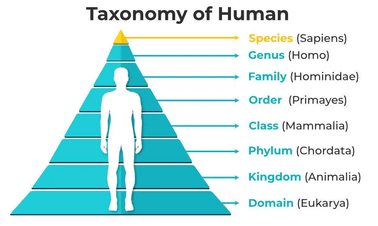

Genetic

I’m going to kick off by talking all things genetics. There are an increasingly large number of vampire movies and TV series where the vampires that featured were born vampires. This includes movies like Abigail, Perfect Creatures, the finale of the Twilight series, but also TV series such as A Discovery of Witches, First Kill and Vampire Academy. Sometimes within these there are vampires that are made through other means (discussed below) in the same world. Often these genetic vampires exist as a separate species to their Homo sapien neighbours either openly or in hiding.

There is often much discussion about where the vampire myth comes from, and in many way these stories of genetic vampires who are birthed through a similar route to standard human deliveries, links in most with what is considered to be a real world inspiration for many vampire myths. The origin is thought to be linked to a rare inherited condition known as Porphyria, the presentation for which may account for for some of the common components of vampire portrayals.

Porphyria is a rare, inherited blood disorder that occurs when the body can’t convert porphyrins into haeme, a vital component of haemoglobin. The resulting symptoms vary depending on the type of porphyria. Acute porphyria presentations include symptoms such as gastro intestinal pain and symptoms like nausea and vomiting – symptoms that are often portrayed linked to vampires attempting to eat normal food. Whilst cutaneous porphyria symptoms include pain, burning and swelling in response to sunlight, skin fragility and a tendency towards skin blistering – all of which are frequently included as vampire responses to exposure to sunlight.

D. Montgomery Bissell, M.D., Karl E. Anderson, M.D., and Herbert L. Bonkovsky,

N Engl J Med 2017;377:862-872

VOL. 377 NO. 9

Interestingly, in some of the genetic origin vampire stories, the impact of some of the limitations of the lifestyle limitation of traditional vampires are not so extreme. In some of these cases they can be seen in daylight, although not for long and don’t enjoy it, and they may be able to tolerate some, if not all, of human food. They are possibly therefore most aligned to their real world inspirations. I could write pages and pages on this, but infection is where my heart lies so I’m going to crack on.

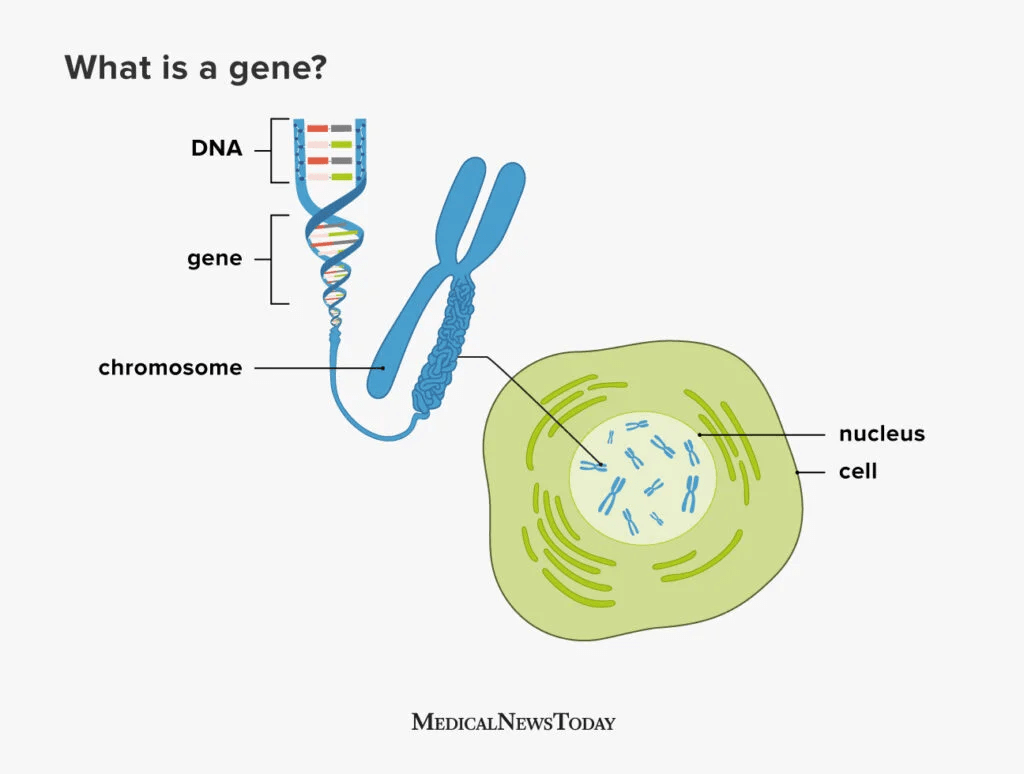

Virus, parasitic, others?

Now we’ve covered off those born vampires, let’s move onto the most common version of vampirism outside of the traditional Dracula more mystical inspiration, that is vampires who are created linked to transfer of infection by blood or other means.

There are three main ways that this commonly comes into play:

- Viral causes

- Parasitic routes

- Bacteria intoxication

I’m still trying to find a vampire movie where the main infectious agent is fungal, but it seems that most of the movies based on fungi are linked to zombie outbreaks. That makes a lot of sense, due to the fact that fungi are eukaryotes (like us) rather than prokaryotes (like bacteria), and so fungi tend to be linked to changing behaviour linked to interfering with the human nervous system. If you’ve seen a vampire version though please do let me know as I’m collating a list of where different organisms might come into play.

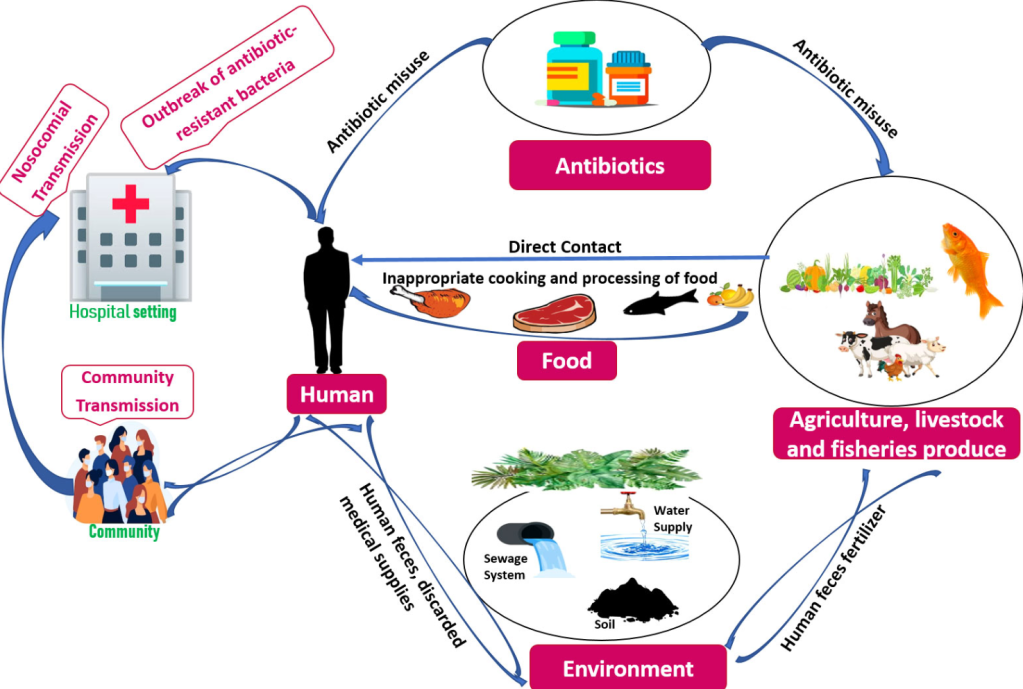

By far the most common route depicted is where the causative agent is a virus. Viruses are featured in movies such as Blade and Daybreakers and TV series such as Ultraviolet. This is because viral transmission in general is associated with transfer of bodily fluids, be that faecal-oral, respiratory via saliva, bodily fluids such as breast milk, or in the case of vampire movies via blood.

The most uncommon causative agent I’ve discovered is the parasitic cause of vampirism as shown in The Strain TV series. During the series transmission of the virus to create a full vampire is via something known as ‘The White’ that contains parasitic worms. These then lead to anatomical changes, including the growth of a proboscis that enables the biting and transmission of the parasite to others.

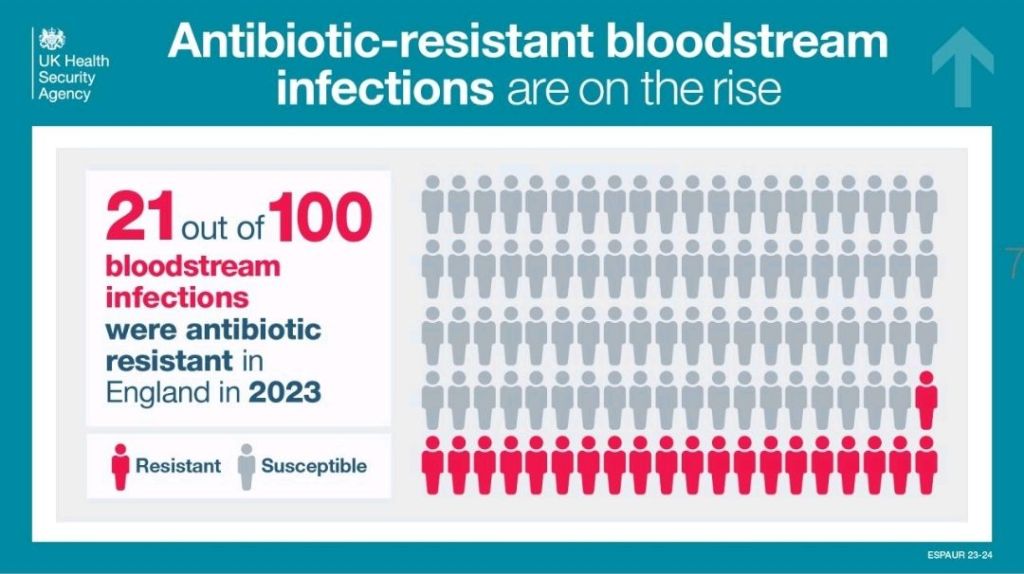

Bacterial coverage is mostly linked to potential methods of intoxication that supports the control over humans by vampires. Rather than being a direct cause of the vampirism, this seems to be about how transfer of the bacteria releases, or causes anatomical change, which then changes behaviour via things like hormonal or neurological changes. I’ve talked before about why bacteria may feature less in horror movies than other causes, but this can mostly be summed up by the fact that audiences tend to know more about bacteria and therefore it is less tempting for writers, but also horror tends to sit better in ‘the possible but not too close to us’.

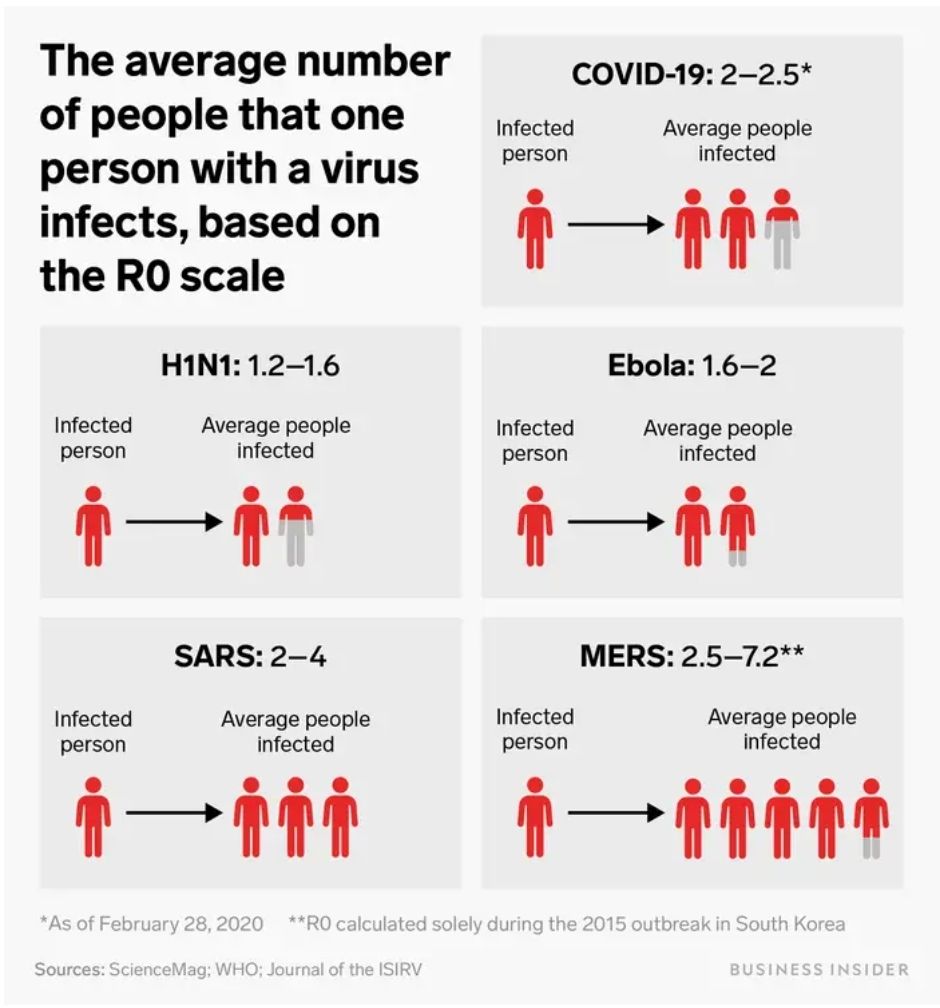

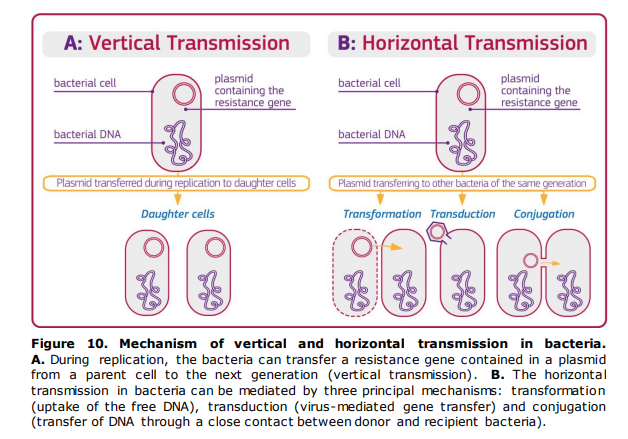

Transmission

Obviously it’s not just the infectious agent that is important, but the mode of transmission for that agent. This being all about vampires the biggest mode of transmission is by bite, but it’s not always so straight forward. In mystical vampire movies, there’s usually a whole lot of removing of the original human blood and then transfer of the vampire blood, leading to a mystical baptism and rebirth. Infectious causes are much more one way, any bite could lead to someone turning into a vampire and the most important thing is load related. If someone is in contact for longer, if more blood is drunk and therefore more saliva and fluids exchanged, then the chances of conversion are much higher.

It’s not just blood as a bodily fluid that features in conversion during vampire movies. There are also films, such as Requiem for a Vampire and Trouble Every Day, where vampirism is treated more like a sexually transmitted disease, rather than transfer occurring during feeding on the blood of their victims. It seems that these films have increased since the 1980s, maybe as a result of fear processing linked to the HIV/AIDS pandemic during that time period or maybe because our knowledge about and ability to detect infections has increased and therefore there are a larger part of the collective public awareness. It will be interesting to see how the SAR CoV2 pandemic will impact this further.

The most unusual transmission, and one that aligns most highly with blood borne transmission is the presence of congenital transmission as featured in Blade. Where the main character Blade becomes a vampire hybrid by acquiring the vampire virus at birth, due to his mother being bitten and placental crossing of the virus into his blood stream. As a result, he exhibits some of the characteristics of a vampire due to the virus, but the effects are attenuated linked to his exposure route. It can often be that congenital infection presents differently to primary infection via other causes, and it appears vampirism is no different.

The other variable is linked to the time to turning once the infection has been introduced. I would speculate that this too is load related, as well as the infectious agent behind the symptoms. Viruses, for instance, are likely to reproduce and induce change at a much higher rate than anything linked to bacteria or parasites. This is partly due to their reproductive rate, but also linked to the level of dose that tends to be available. The exception to viruses resulting in the fastest change is likely to be bacterial intoxication and influencing. As the toxin acts immediately, when this is present in media and TV the change is almost instantaneous, but also time limited and therefore requires top up or re-application. Not all impacts are until beheading, some require a more time boundaried set of interventions.

Interventions

Once your characters are aware that vampires exist within their mist, then they will want to look for actions in order to protect themselves. One of the classic ones as featured in many movies, including the classic Lost Boys, is garlic.

In some ways the impact of garlic makes even more sense if you think of vampirism through an infectious transmission route, as garlic has been considered to have anti-infective properties for a long time, although warning you may have to ingest a LOT of it!

Another common feature in vampire movies is the roles that animals play as protectors. For instance, in 30 Days of Night, the vampires kill all of the dogs before they launch their main attack. This kind of thing also often happens in films and TV where vampires are hiding in plain sight. It could be that they are taking out animals as they don’t want to be found, and animals are easier than humans, but I have another proposition. There are a number of infections where animals can be used to sniff out and identify infected individuals. Therefore, if animals could detect vampires they are much more likely to be a risk and warrant removal. Animals could therefore act as a front line of diagnostic defence to enable you to tell friend from foe.

Having determine that a common weakness of vampires is their damage response to ultraviolet light (UV), films such as Underworld weaponise light against the vampire protagonists. Light, and especially UV-C (200 – 280nm), has been known to impact viruses and bacteria for well over 100 years. When light is in this frequency is can damage both RNA and DNA, resulting in cell death, and it is possible that if the infectious agent is the only thing that is keeping your body moving the damage would be more pronounced. We’ve also discussed how the lack of some biochemical pathways can lead to UV-C causing much larger amounts of pain an damage.

Normally, penetration of the light to cause damage might be an issue, but if you are using bullets or other means this may not impact. The most important thing I have to say here is, that despite what is shown in Blade 2, light does not bend around corners. This is also important for when you are considering using UV-C in hospitals to support cleaning, it doesn’t have good penetration and doesn’t go around corners of work in shadows. Using UV-C may work against your vampires but you are going to need to think carefully about where you use it so it does what you think it can.

Vampire movies have amazing world building and are often my favourite genera in terms of their string internal logic. I love the fact that so many types of infection and route of transmission that reflect real world cases are present as part of these pieces of entertainment. They can actually teach us a lot, even when we don’t realise it, and so much of it has origins in real world knowledge, even if only loosely. So, this Halloween evening find one you haven’t seen before and let me know which intervention you would use to stop your town being turned into creatures of the night!

Before I go, I thought I would share a few of the previous years Halloween blog posts in case you are looking for some more spooky season and infection reading:

Let me know your favourite vampire movies and if there are any other infection related Halloween topics I should cover.

All opinions in this blog are my own