As Girlymicro has a) got tonsillitis and b) attempting to run the day, todays blog is a guest blog brought to you by frequent Girlymicrobiologist contributors and Environment Network stakeholder members: Sam Watkin and Dr Claire Walker.

It’s the most wonderful time of the year! Today is the Environment Network meeting where we gather together to talk all things environmental risk assessment. This is a network for people in clinical, scientific and engineering roles within the NHS and other associated organisations who are interested in the role of environmental infection prevention and control in preventing infection. Despite being an immunologist (Claire Walker) for most of my career, this is one of my favourite meetings of the year. Everyone is deeply passionate about what they do and how we can work together to exchange ideas and improve practice.

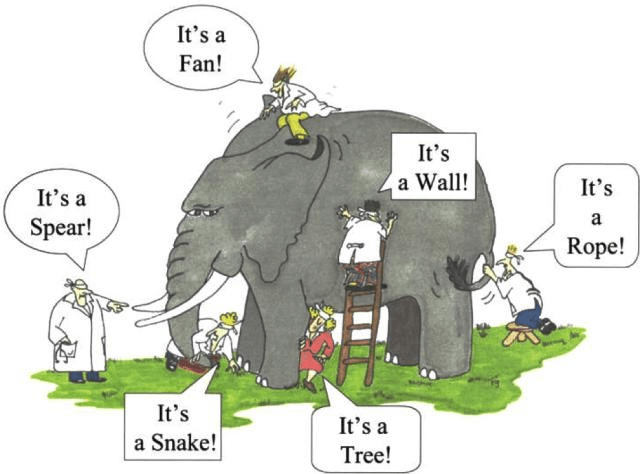

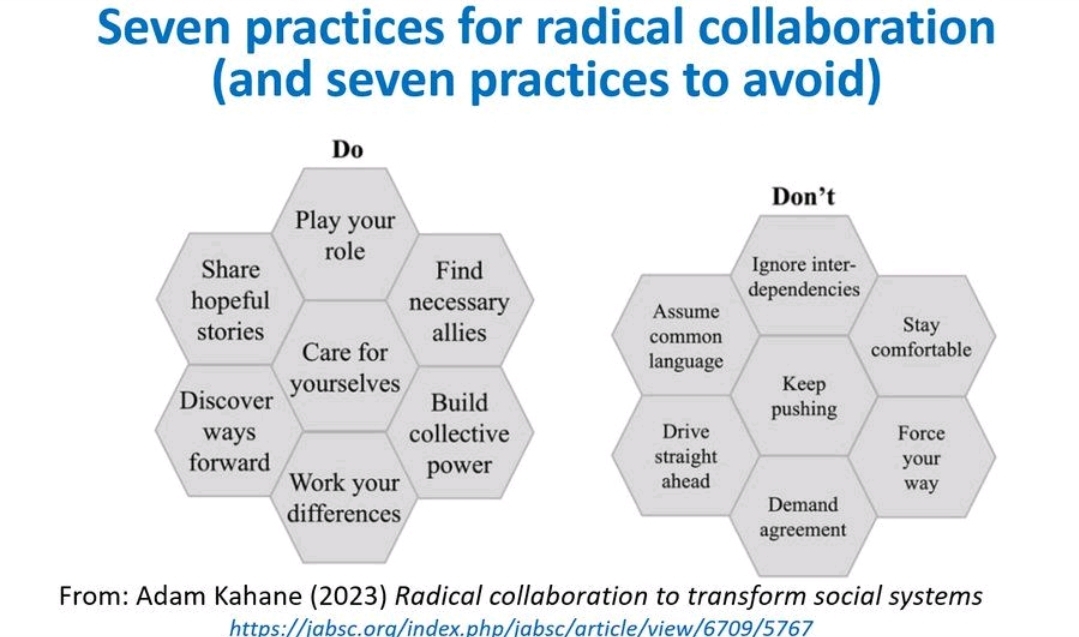

Too kick us off, we have the wonderful Professor Elaine Cloutman-Green and Lena Ciric welcoming us to a day of interactive sessions on key issues in the field. Prof C-G sets the scene for our day introducing the concept of our different perceptions of risk assessment and the challenge of unexpected consequences. Of course we understand the triumvirate of identify, understand and mitigate problems but how an engineer approaches risk is quite different to how a clinician might. As Prof C-G says clinical risk assessment is not a zero harm game, it is about controlling real rather than theoretical harm. A balance needs to be stuck between what is most appropriate for the patient – we could keep patients in bubbles and not even have healthcare professionals approach them, but I doubt that patient would fare very well! There is a need to balance the approach of the clinical and the engineer to find an optimal position to minimise harm. To make these decisions we need to consider the interaction between organism, patient and the built environment in order to work out what the control measure should look like. Problems aren’t simple, we need to accept and embrace that risk assessment is a complex process. And perhaps most importantly we need to take the time to see the perspectives of others, or we might never see the elephant in the room.

Risk assessment has the potential to make use all uncomfortable, as scientists we do not enjoy the unknown. In good risk assessment A plus B does not always equal C, it might do 50% of the time so we have to rely on our best judgement. Moreover, risk is not static. All patient and clinical environments are quite different as we need to pick the point that works for that situation – National guidance can never cover all of these unique situations. A multi-disciplinary team approach is essential to ensure we are asking the right questions.

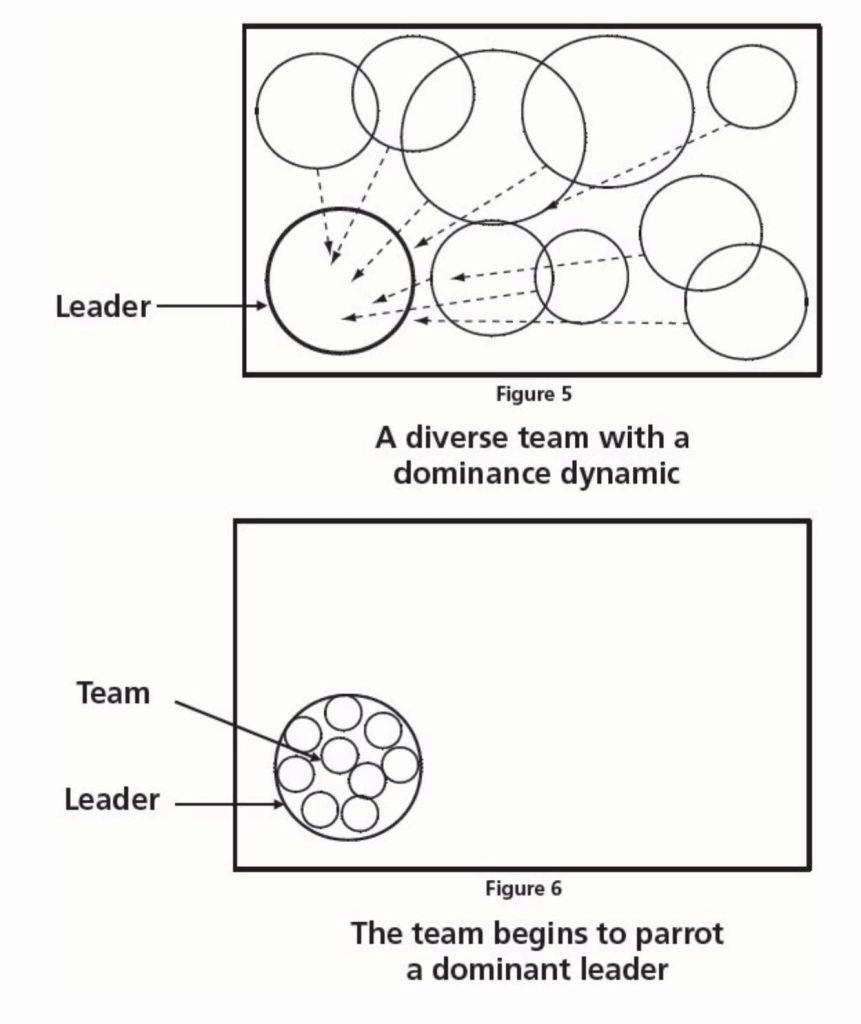

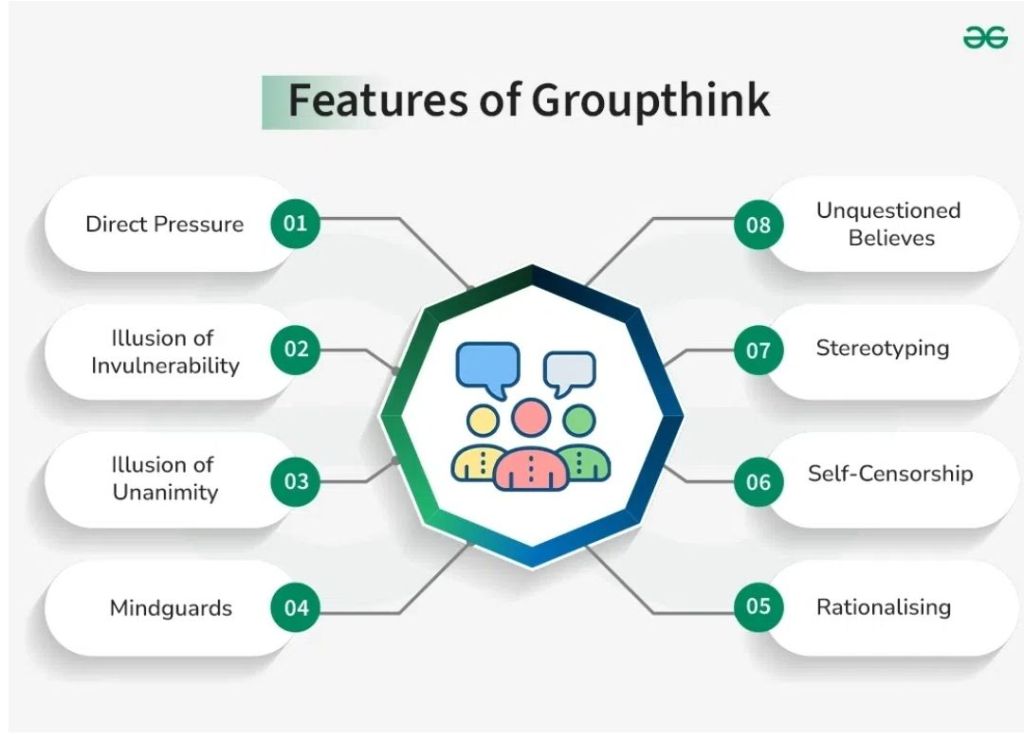

Next up we have Dr Susanne Surman-Lee giving a talk on combining clinical and engineering risk and why working in silos hinders risk assessments. Silo working at all levels, even within a team, can cause a raft of problems, with poor communication, different priorities, resource conflicts and inefficiencies. This can mean those in each silo work to their desired outcomes, not taking into account what other requirements may be. The danger of this is that it ultimately increases the risk to patients.

A poll found that the event was well attended by people from a range of disciplines, covering many relevant professions to environmental infection control. We often all want different things from a building, be that aesthetic, cost or usability. What is critical, and reflected in new guidance, is that the purpose of a building must be to put the patient first.

To escape working in silos, the audience recognised that communication is absolutely key. Working as a single team, sharing respect, data sharing and fostering a collaborative culture is all needed to break down individual working silos. This enables the project team to work as a single unit, supporting faster, safer decisions across strategic levels.

A set of examples on real-world decision-making processes highlighted not only the importance of accurate record keeping when it comes to decision-making, but also what can happen when an IPC challenge is only viewed through teams working in silos.

When considering waterborne infection risks, a multitude of challenges, both from an engineering and non-engineering standpoint must be considered. This can range from inadequate usage leading to stagnation, poor hygiene during installation and poor labelling, outlet misuse, poor cleaning techniques and inappropriate assessment if transmission risks as examples.

Ultimately, we must consider the problem as a whole. Different hazards and sources of pathogens overlap, meaning we must work across disciplines to mitigate risk. We also must gather information from multiple sources to identify risks to make sure a risk isn’t overlooked.

Updated guidance has recently been produced following an outbreak of non-tuberculous Mycobacteria for the safe design and management of new buildings calls for collaborative working throughout the project, with continual risk assessments and project ownership by the trust. Having a multidisciplinary approach can help effectively design and manage risk, improving IPC risk assessment and decision-making procedures.

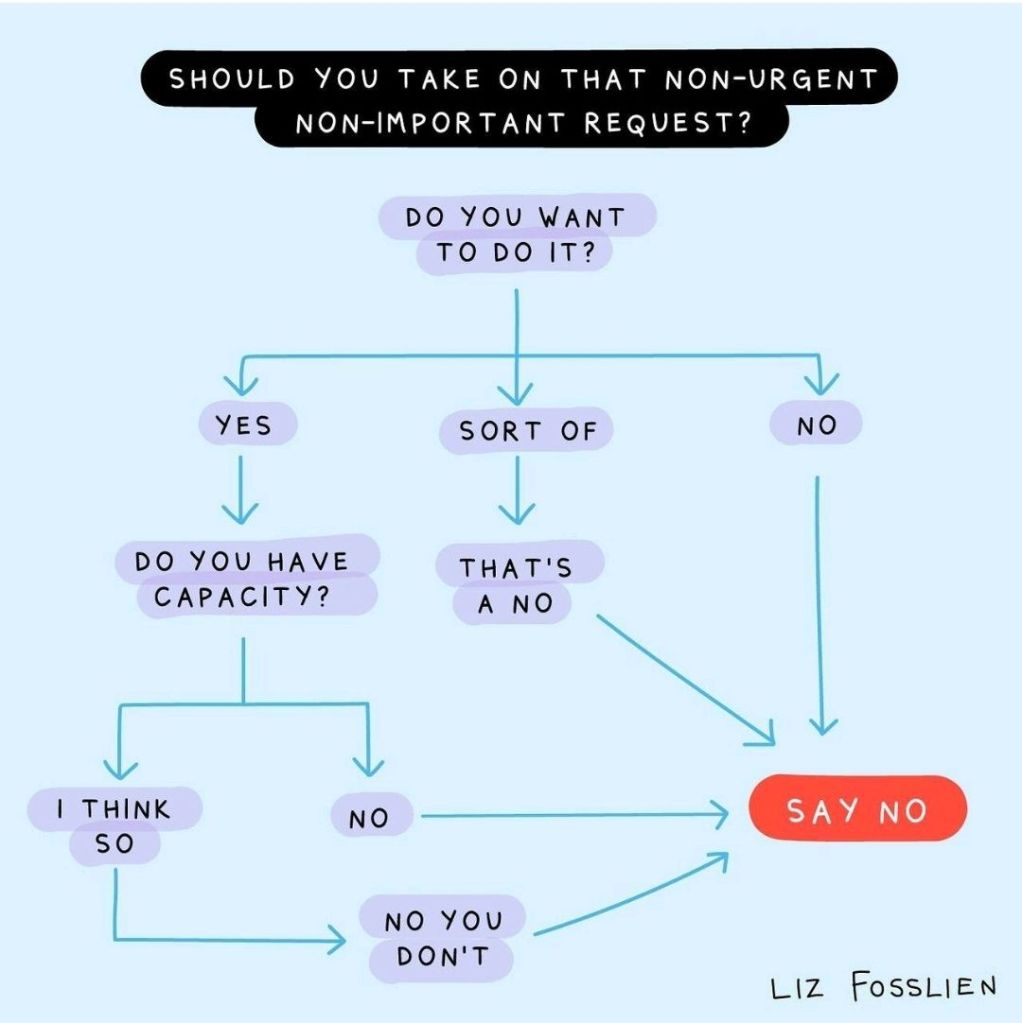

In this final session before some essential caffeine, we have Andrew Poplett taking us on a whistle stop tour of derogation management. Derogations, like puppies, are for life – if you agree to one you must be sure as they are extremely difficult to reverse. We know that unless specifically stated much of the guidance in not mandatory. However departure or derogation from HTM should provide a degrees of safety NOT LESS THAN that achieved by following the guidance laid out in the HTM.

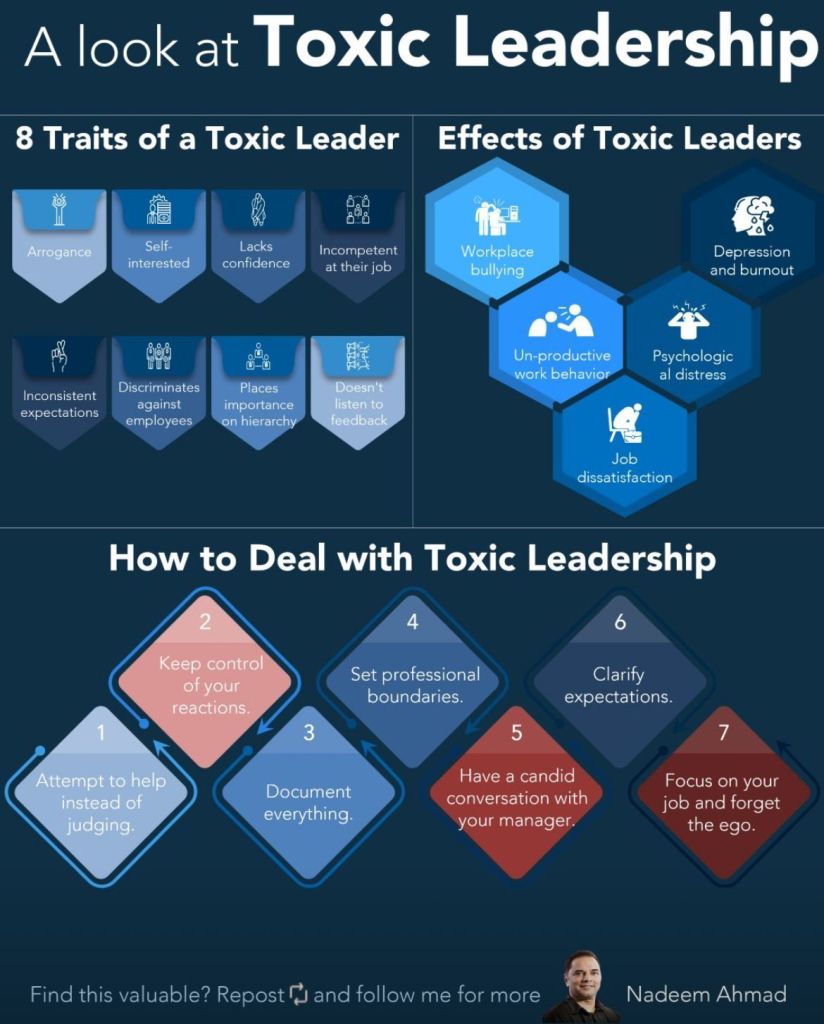

A derogation is an exemption from or relation of a standard or rule but it must be carefully managed, documented and justified. It must be risk assessed and cannot be to reduce costs. Of course, the bugs haven’t read the HTMs and they really don’t care about the budget! Minimum standards and patient safety guidelines cannot be derogated, but for those for those ‘nice to haves’ there is some wriggle room. So why do we want to derogate? Situations like conflicting guidance and refurbishment of existing buildings. Once again we are lead to the conclusion that these decisions must be the result of a multi-disciplinary team approach and risk assessments – these decisions can’t be made solely by a financial manager, an engineer, a microbiologist or infection prevention and control, but requires a meeting of minds to reach the right conclusion. The cornerstone of derogations is communication, ideally reaching a sensible and agreed consensus that balances risk, compliance and other important factors (like cost!). Ego needs to be left at the door or we might need to start hiring some referees!

If you break the rules, you really need to document why, what, who and when. It’s not to say that we shouldn’t, as we know every circumstance is difference. But transparency is essential to the process, and they do need to be reviewed regularly. As a final thought, Andrew invites us to consider that it is important to remember that it is always cheaper to invest the time upfront because short cuts tend to end in expensive disaster.

After a quick coffee break, we have Louise Clarke from GPT Consult discussing capturing water and ventilation risks as part of governance strategies. First off, we must understand what risks we actually need to assess and manage. We often have aging infrastructures, changes in usage, hidden infrastructure, access challenges and maintenance works. Not only that, how people use and view spaces factors into the risks we must assess.

When assessing risk, it must be suitable and sufficient. But what does that actually mean? It depends on what you are trying to deliver, what you are looking for and what is being managed. Five-by-five risk matrices do not necessarily capture the complexities of these risks. Not only this, a huge amount od information is required for effective assessment. Factors like patient factors, unique building features, data from building management systems must all be considered. Not only that, but there are a large amount of unknown factors which need to be considered. The current state of a building and the equipment in place is important to consider, with the impact these may have in the future on risk taken into account. Overall risk profiles are needed but challenging to achieve as many people view the risk of a setting from different perspectives.

All risk assessments must be performed within the appropriate legislation. This covers government legislation, approved codes of practice and best practice guidance (such as the HTMs). To ensure that all standards and met and the process of derogation is appropriately followed, governance structures have to be followed. But these structures themselves can be difficult to navigate. The reporting of information gathered from the building (such as information from the building management system) can be challenging through these structures. How do we ensure the data is appropriately recorded, interpreted and presented? Do governance structures effectively allow for this process and make sure that the data collected useful and enables risk assessment? So, how should the data we collect from the building be presented? As with many things, it depends. What the intended use of the information is, how is needs to be interpreted and disseminated all matter.

Typical governance structures include water and ventilation safety groups. These groups serve to bring together estates, infection control, representatives from the relevant clinical units, contractors in order to assess risk and make informed decisions. Are such meetings suitable to address risk? The volume of data that must be presented, understood and used to inform decisions is massive, and these meetings are time-constrained. A lot of the processes will be informed by the risk appetite of the organisation. Information may not be available and work may not be possible. As such, appropriate record keeping and reporting is crucial. Taking this all in, governance strategies which to be implemented must be practical, realistic, effective, suitable and sufficient.

Sadly Dr Derren Ready from UKHSA is enjoying a marvellous holiday so we have a recording from him today. We are venturing into the field of community risk assessments and the considerations that are notably different from in the hospital. There are significant challenges, as highlighted by the consideration of the prison system where an outbreak might further restrain the liberty of the prisoners impacting significantly on their mental and physical wellness, thus careful balances need to be struck. In essence, the challenges of the community require a different set of questions to be answered in risk assessment.

In community risk assessment the first stages fall to information gathering and fact checking. Information gathering might focus on the clinical, epidemiological, microbiological or environmental factors. Context of the information should be considered. In public health we often act on suspicion as time is of the essence. In the initial stages there is often simply anecdotal information and there is a need to all the facts to be checked through this dynamic process.

UKHSA bases its risk assessment of five key areas. The first of which is severity which is the seriousness of the incident in terms of the potential to cause harm to individuals or to the population. This is graded from 0-4 where 0 has a very low severity like head lice in a school whilst class 4 are extremely severe illnesses which are almost invariably fatal, like rabies or Ebola virus outbreaks. The second area is uncertainty, how sure are we that the diagnosis is correct based on epidemiological, clinical, statistical and laboratory evidence. The third area is the likelihood of the organism spreading covered by an assessment of the infective dose, virulence of the organism, mode and routes of transmission, observed spread and susceptibility of the population. Again the areas are graded from 0 to 4 allow qualification of the potential risk. The fourth area is intervention, what could be done to alter the course of the outbreak? This ranges from minimal, non invasive procedures like handwashing to an urgent mass immunisation campaign or withdrawal of all contaminated food products. Clearly some outbreaks don’t lend themselves well to specific interventions an example would include responding to a cluster of vCJD disease where remedial intervention is particularly challenging. The last key area is context. The easiest way to consider this is to think about the broader environment in which the event is occurring. Factors like public concern, attitudes, expectations, strength of professional knowledge and politics have the potential to influence decisions about the appropriate response to an outbreak.

The best way to approach this complex process is through the use of a dynamic risk assessment where the risk assessment is continually reviewed throughout the outbreak. This allows UKHSA to make the best possible decisions based on the best information available. These dynamic risk assessments can be classified an routine, standard or enhanced based on the response required to an event. The take home message is very much that risk is not static and we need robust frameworks to ensure we make the right decision at the right time.

In our final talk of this morning, we have our own soon to be Dr Sam Watkins from UCL/UKHSA. Sam’s research interest in detection of surface based pathogens in the hospital. Surfaces can be come contaminated and play an important role in the spread of infection around the hospital. Once considered tenuous, the role of surfaces in the persistence of healthcare associated infection is now well established for several pathogenic organisms. The current standard is for surfaces to be visibly clean but there is no guidance on assessment of microbiological hygiene of surfaces. It’s extremely important to remember that just because something looks clean, doesn’t mean it isn’t crawling with bugs! Again, we must consider that a one size fits all approach cannot be enforced across the NHS as we have so many different situations and patient requirements.

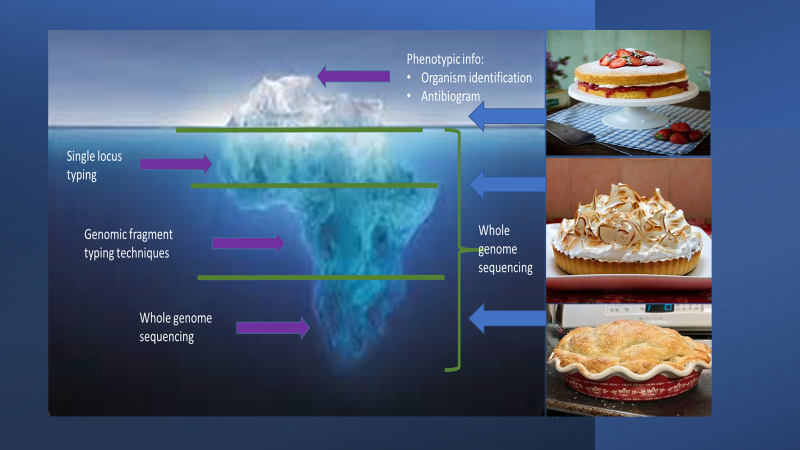

Sam’s research focuses on development of new tools for assessing surface-based transmission risk. Surface sampling can be many different things from contact agar plates, to specific swabbing or sponges, to PCR identification of specific viruses in a outbreak scenario all of which have different purposes. All of this information can help support clinical risk assessment and the actions of infection prevention and control. Currently surface sampling is most commonly used as a retrospective measure after a clinical incident during outbreaks. Sadly there is little guidance or framework in place to guide process in this area. Furthermore, the identification of a pathogen on the surface doesn’t provide sufficient information on if this is the cause of the outbreak. Sam’s work has been to gather prospective evidence gathering through surrogate markers which mimic a microorganism in the environment without posing any infectious risk. In Sam’s work, he has been using cauliflower mosaic virus across an outpatient and inpatient haematology oncology unit. Three markers derived from the genome of the cauliflower mosaic virus were used and inoculated on various risk level surfaces. After 8 hours the swab samples were collected from pre defined sites. The movement of the surrogate markers across the unit were investigated over the course of five days. Within 8 hours there was widespread movement of the markers across the outpatient unit. A slightly less dramatic spread was noted in the inpatient site. From this we see that there is huge variability in the dissemination of markers, markers deposited on high risk sites where identified in a greater number of places. Paediatrics certainly adds an additional dimension to this work, with children spreading viruses through an exciting game of hide and seek in the department! An important take home message here is that a one size fits all approach is unlikely to be successful, given the highly varied nature of clinical settings. A unique approach to surface-based transmission risk assessment and mitigation may therefore be needed.

With the morning session drawing to a close. We look forward to a delicious lunch, more coffee and interactive case based discussions this afternoon!

If you want to find out more about environmental infection prevention and control and future events you can check out the Environment Network here. Girlymicro has also previously posted about risk assessment and the role of the environment in healthcare settings, links to more posts can be found here. The main theme of the day was that we all need to get out of our silo’s and talk more, so let’s start that change by being bold, starting conversations and getting out of our boxes!

All opinions in this blog are my own