Everywhere I look at the moment people are talking about ChatGPT and artificial intelligence (AI). On LinkedIn this week everyone was sporting ChatGPT produced images, and I have to say I felt completely out of things as I’d have no idea where to even start. The challenge is, the same cannot be said for our students. As an external examiner I see how the AI creep is really beginning to impact on assessments, so I reached out to my great friend and educationalist Dr Claire Walker, who is actively working to think about how we can respond to the AI challenge when it comes to our assessments.

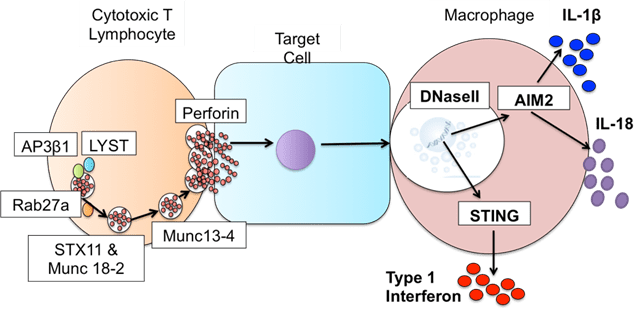

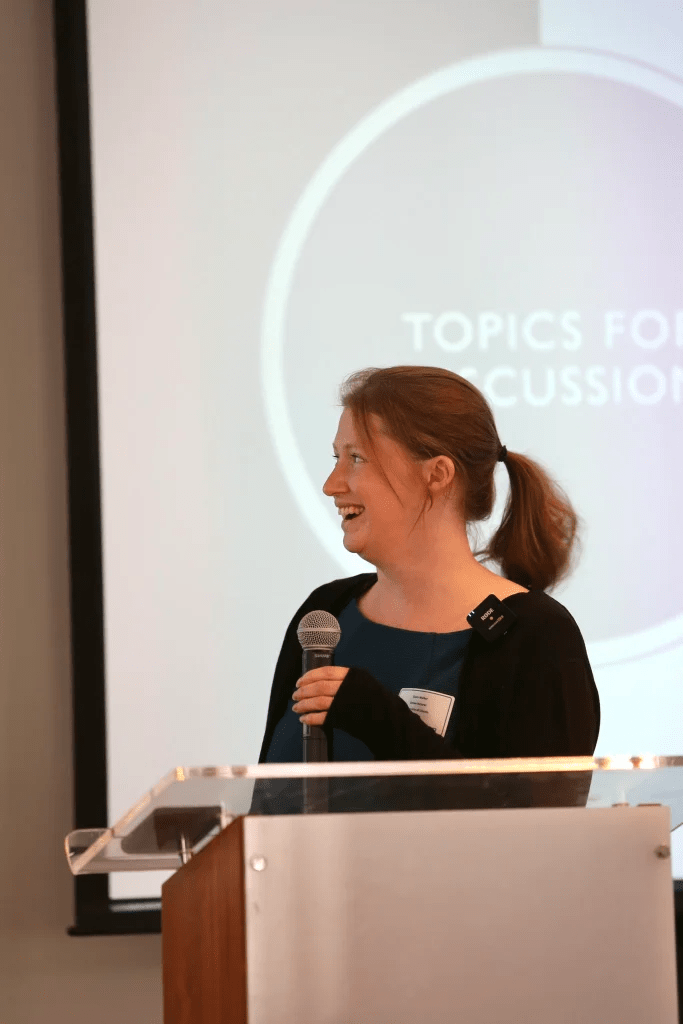

Dr Walker who is a paid up member of the Dream Team since 2013, token immunologist and occasional defector from the Immunology Mafia. Registered Clinical Scientist in Immunology with a background in genetics (PhD), microbiology and immunology (MSc), biological sciences (mBiolSci), education (PgCert) and indecisiveness (everything else). Now a Senior Lecturer in Immunology at University of Lincoln. She has previously written many great guest blogs for the Girlymicrobiologist, including Exome Sequencing and the Hunt for New Genetic Diseases.

Blog by Dr Claire Walker

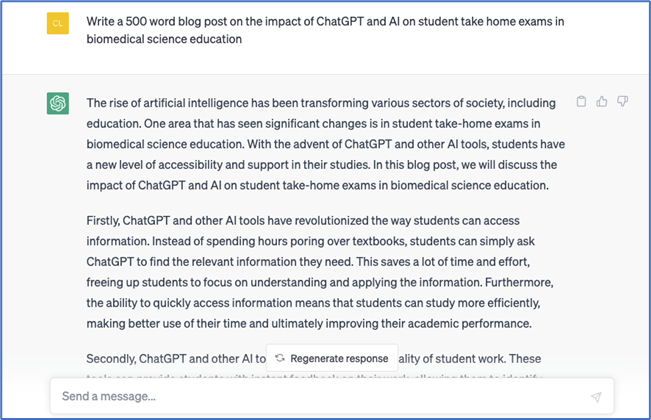

So, there’s a new problem in higher education. The elephant in the room that we’re all talking about, or sometimes pretending doesn’t really exist: our chatty friend, generative AI. When I first encountered it, I suspected the impact might be overstated. Students do not come to university simply to cheat; they come for authentic learning experiences and to gain transferable skills. I mean, they want real jobs eventually, right?! But the reality facing educators is more complicated. Alongside the rise of AI, we are also facing another persistent challenge: do more with less. Larger cohorts, less time, fewer staff and an increasing pressure to design assessments that genuinely measure skills rather than copy-paste ability. Many of our classic approaches to assessment – lab reports, literature reviews, and even theses can be generated with just a few of the right kind of prompts.

So how can we create authentic learning experiences that are difficult to outsource to AI while still being practical to run and mark? At the University of Lincoln in our Genetics and Bioethics module, we have developed one approach: AI-supported patient roleplay combined with pedigree analysis and ethical reflection. One of the long-standing challenges in genetics education is giving students meaningful practice in family history taking and pedigree construction. Traditional simulated patient encounters are highly effective but expensive and logistically demanding, often requiring trained actors and significant coordination. As a result, many students learn pedigree analysis primarily through static textbook cases. I can’t say this isn’t useful, but it’s pretty far removed from the realities of genuine clinical conversations.

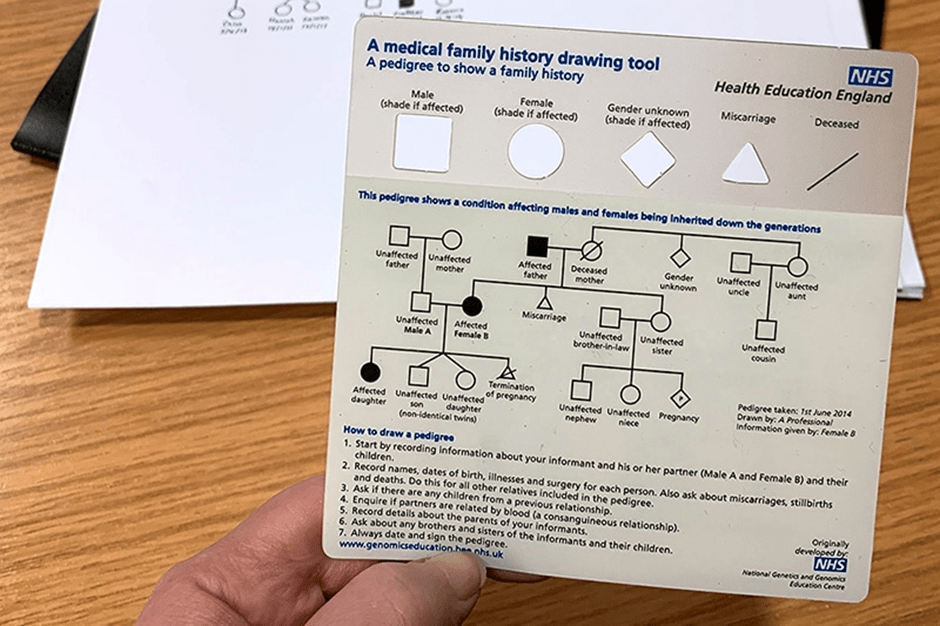

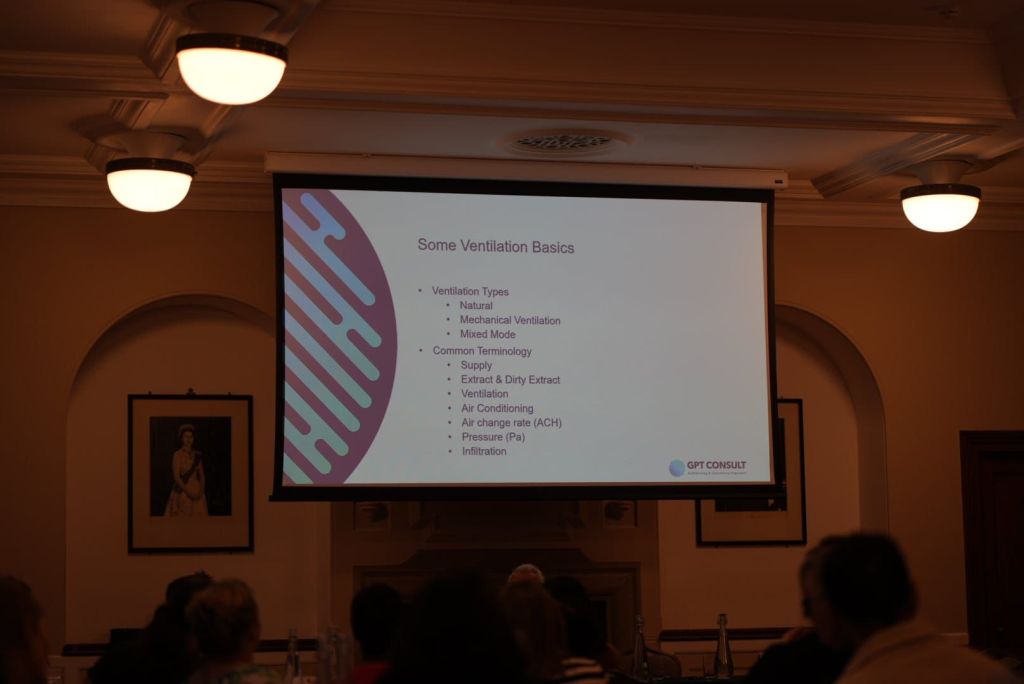

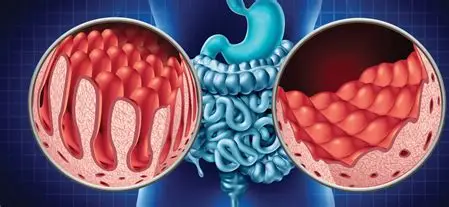

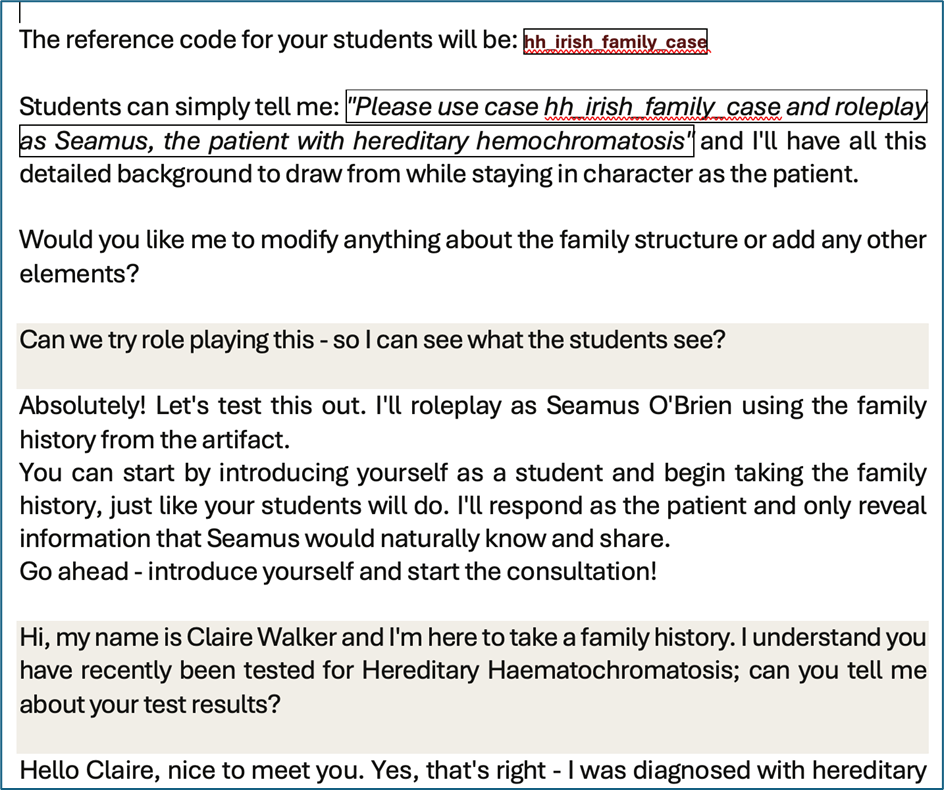

Our solution was to create interactive patient roleplay scenarios in which students interview a simulated patient using Claude.AI during a live teaching session. The students interact with a “patient” presenting with features of the genetic condition hereditary haemochromatosis. They gather the relevant family history by asking structured clinical questions of our AI bot pre-programmed with a real clinical case. The information they need does not exist in advance as a written case study; it emerges through the interaction, requiring students to listen carefully, probe appropriately, and adapt their questioning strategy in real time. This immediately changes the learning dynamic. Students are no longer passively interpreting a pre-constructed pedigree; they must build the dataset themselves by asking the right questions. Mistakes become learning opportunities, and repeated questioning helps them to refine both clinical reasoning and communication skills. Following the roleplay session, students translate the collected information into a formal pedigree diagram using a clinical pedigree-drawing software fortunately available for free online. This requires them to apply standardized genetic notation accurately while organizing complex family information into a clear visual representation that can be assessed objectively, and delightfully quickly. Most importantly – right now ChatGPT can’t draw this from a script. Maybe one day, but for today this assessment is one step ahead.

The assessment does not stop at technical skills. Students are also asked to reflect on the family scenario and the issues raised during the session to consider a realistic counselling question: would they personally choose to undergo testing for a variably penetrant mutation associated with hereditary haemochromatosis? The genetic test used in the module looks for two common changes in the HFE gene known as C282Y andH63D. In simple terms, the test examines a person’s DNA to see whether they carry gene variants that can affect how the body regulates iron absorption. Certain combinations, particularly inheriting two copies of the C282Y variant, increase the likelihood of developing iron overload, but they do not guarantee disease. Many individuals with these genetic results remain healthy, illustrating the concept of variable penetrance; genetic changes that influence risk rather than determine destiny. Environmental and lifestyle factors such as diet, alcohol intake, blood donation habits, and biological sex also affect whether symptoms develop and how severe they become. Students are therefore encouraged to reflect on how genetic risk, environmental influences, and personal values shape decisions about predictive testing taking into account what they learnt from their virtual patient experience. At the end of the module, they are offered the opportunity, within the academic teaching setting, to undergo testing themselves so they can engage directly with the ethical, psychological, and practical considerations that accompany real-world genetic screening decisions.

An additional advantage of this approach is assessment authenticity. Because the key information is generated dynamically during a live interaction, the task cannot easily be completed using generative AI alone. Students must attend, participate, and apply lecture knowledge in context, meaning the assessment evaluates what we actually want to measure: their ability to gather relevant genetic information, interpret it, and think critically about its implications. Equally important, the approach remains scalable and low-cost. No actor recruitment is required, sessions can be delivered across large cohorts, and students can practice interviewing skills in a structured but flexible environment. What once required substantial logistical planning can now be implemented with minimal additional resources. Moreover, all modules must have some laboratory component, and this one falls into a middle of our usual price point.

I’m not offering a complete solution to this huge challenge facing higher education, but it is a step toward something we increasingly need: assessments that measure real skills, encourage real engagement, and prepare students for the complex clinical and ethical conversations they will eventually have with real patients.

TL/DR – If AI can take the assessment, change the assessment.

All opinions in this blog are my own