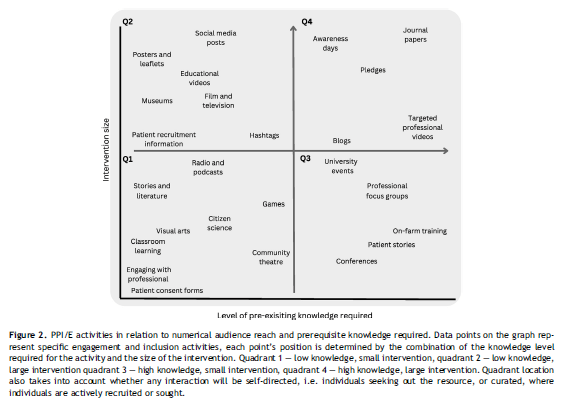

In January 2022 I posted about a secret ambition I had, to turn the Girlymicro blog into a book. Now it’s taken a while and and I finally have the first 2 chapters and a non-fiction proposal put together. I thought as I start to send it out I would also share chapter 1 here as a way of owning my journey and showing progress.

I became a scientist because science is embedded in all of our lives, in every act we undertake, from vaccinating our kids to driving a car to work. Despite this, the people who undertake scientific work, the scientists, are often seen as remote or ‘other’. If you watch TV or movies, scientists are either the villains or super smart people who live anything but normal lives. This situation has only been amplified during the pandemic, where public disagreements amongst scientists has demonstrated that science is anything but black and white, and has made it possible for increasing amounts of disinformation and medical anxiety to spread.

At a time, post pandemic, when science, especially infection science, has become more prominent than ever before and yet somehow has also become more veiled by commentary linked to politics and the media. Scientists have never been more significant, yet paradoxically they are seen less as people than ever before. I want to lift the veil shrouding what it is like to work in science and how to become a scientist. This book, linked to the Girlymicrobiologist blog, aims to share the highs, lows and frankly weird aspects of working as a Healthcare Scientist in the NHS and what it is like to be a female leader in the modern workplace. It will talk about what it is like to be a normal girl, with normal grades who ends up advising nationally during a global crisis. How she got there, stayed there and managed to maintain her sanity and sense of self whilst doing so.

Chapter 1: It Was the Best of Times, It Was the Worst of Times

On the 13th February 2020 (roughly a month before we went into lock down) I posted the below on my personal Facebook page:

“As Coronavirus progresses and makes (what most of us feel) is a slow and inevitable move towards being a pandemic, it’s weird how different it feels from the other times I’ve been here.

This will be my third pandemic. The first was swine flu in 2009. There, we had treatment options, we knew that some of our drugs worked and that a vaccine could be developed. Middle Eastern Coronavirus (MERS) has been grumbling on for years, but although we get query cases and the individual patient impacts are great, it’d always been too virulent to really establish itself in widespread transmission. Now we have SARS CoV2 (COVID-19 is the clinical condition). The characteristics of an influenza outbreak are well documented and so can, to an extent, be predicted. That isn’t what we have now.

Most pandemic plans focus on mortality but now it’s the mass disruption that is likely to be the issue. Individual mortality impact is likely to be slight but we may still be removing 30% of our working population for 14 days. That will impact travel, infrastructure and healthcare. A vaccine is going to be difficult to develop and we don’t know yet what drug combinations will work, if any. Most people will be mildly unwell (still feel rotten but not hospital sick). So, from an individual standpoint there is no need to panic. From an organisational standpoint it feels unprecedented.

As we’ve seen nothing like this before it’s unpredictable. I’ve had three requests to go on ITN to talk about it but I’ve declined as I have no evidence to present. This is a slow burn that now looks unlikely to fizzle but how things will transpire is far from certain.”

When asked by a friend what would happen if it became a pandemic, I replied that it would take 2 – 3 years for us to find a new normal. Looking back on it today, over 3 years later, it’s strange to think of the things I had right, and the all the things that I could never even have imagined, after all we were in territory that no working scientist has ever experienced. In all honesty I had no idea what surviving for that long in Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) would look like or the personal impact it would have.

So who am I? I’m Elaine, a girl from Birmingham who went to state school, wanted to win an Oscar, always asked a few too many questions for the comfort of her teachers, and ended up working as a scientist. I’ve worked in healthcare for over 18 years, almost all of them in Infection Prevention and Control, although the Prevention part was only added about 10 years ago. Thanks to IPC I’ve presented all over the world, published papers, worked on national guidance to improve patient care and been fortunate enough to be awarded a New Year’s Honour for services to healthcare. But by far the most important part of all of this is the work is that I’ve done with and for my patients.

You may ask what is it that a scientist actually does with patients? For many years my friends and family have asked the same question. Surely scientists sit in laboratories in universities and not in hospitals? I am what is known as a Healthcare Scientist. I’ve spent all my working life in hospitals supporting not only the diagnosis of what is making people unwell but also, in recent years, managing patients and supporting treatment decisions. Scientists practice within practically all the different parts of a hospital; in imaging (X-rays, CT’s), in checking heart, lung and brain functions, in decontamination, to ensure that surgery is safety carried out, as well as in laboratories working with patient specimens. They are involved in making over 80% of the patient diagnoses that happen in the NHS and so if you are ever unwell and need someone to find out what’s wrong with you, or part of you via a specimen, you will almost certainly encounter a scientist along the way.

I probably don’t look like anyone’s idea of a scientist, I hardly ever wear a white coat, I am also female, short, and wear pink and purple as some of my favourite colours. I spend most of my time these days working directly to support patients, families and the healthcare professionals who are looking after them in order to try to reduce infection risk whilst they are staying with us. I don’t sit around listening to Opera like scientists do on TV, I also don’t know everything scientific from Wikipedia by heart. Instead, I like watching movies, reading mystery books and enjoy my fair share of trashy TV. What I do know is how to find information, hold it all up against each other for comparison and look for themes and ask questions, after all, science is more about asking questions and looking for answers than spouting truths.

In many ways this is why the pandemic has been challenging for science and scientists, if you watch any of us on TV and in the movies, we’re there to give answers, not to explore questions. Therefore, in times of stress and challenge, like the pandemic, the public want us to be the people that give them those answers, the solutions, the ‘fix’ to the problem. As a scientist who works to diagnose and help patient management, I am much more comfortable with this than many of my colleagues; it still doesn’t make me able to answer in absolutes.

As January 2020 had moved into February and more information became available I had already ordered spare pyjamas, phone chargers and everything else I think I might need for an unexpected hospital stay, not because I was concerned about being admitted but because part of me thought that I wouldn’t know if there would be nights when I just needed to sleep in my office, so I put together a grab bag for under my desk and tried to prepare for what might be about to happen. A friend sent me a blanket to keep under my desk. One of the things I always do is run scenarios in my mind, trying to work out what eventualities might unfold, trying to picture various events in order to make sure I am as prepared as possible, both mentally and in terms of what I need to deal with what’s in front of me. Despite that nothing could really prepared me for how things were about to unfold.

It’s a strange thing to think back to that time, now when in many ways I’m exhausted and broken by it. Although it was filled with a level of fear, I’m not sure that I was actually afraid, at least not at the start. There was a sense of knowing that something was coming in a way that others didn’t truly appreciate as I’d been seeing various reports coming out of China since December 2019. There was also a sense of anticipation, a sense that I had spent years training for this. You don’t get into IPC (weirdly) if you don’t like decision making during uncertainty but that often clashes me being more than a little bit obsessed with control. I am both risk averse and excited by the unknown, it’s why I like research, as you always feels like you’re a bit of an explorer. It also felt strangely nice to suddenly be on everyone’s friend list, suddenly people cared what I did for a living. Suddenly we weren’t the nerd squad or health police, we were the people who everyone wanted to involve and ask our opinion. For once it felt like we mattered. This probably sounds strange if you don’t work in healthcare, but it took me over 13 years to get a full-time funded post because no matter how much everyone acknowledges that IPC is important, it’s also not sexy in terms of attracting funding. I’m not separating conjoined twins and being filmed by the BBC, I’m not undertaking the first face transplant, I’m doing the necessary things to keep people safe and hand hygiene is not going to be on the 9 o’clock news – at least not pre pandemic.

At the start of February although things were ramping up it was still within the realms clinically of what I’d experienced during other pandemics. There was the rush to work out if we could develop and validate a test in a matter of days rather than a matter of months. There was dashing about to meeting after meeting working out what systems we had in place to identify patients, were we asking the right travel questions, was there a symptom list we needed to be ticking off. Then there were all the questions about what to do with staff, our staff tend to be one of the biggest routes of exposure to patients when things start, because they are the ones who are going out and about in the world, whereas our patients are often longer term and staying on site. The changes began to come rapidly.

Working as I do, you have friends and contacts working all over the world and the reports started coming back from other countries who were ahead of us in terms of case numbers, and none of the information we were getting was good. The number of clinical cases was in line with our fears, making us reflect on how this might outstrip our capacity, even if in the majority the severity was not that high. The thing you have to remember is that healthcare runs close to capacity all the time, we don’t have lots of spare beds and even if we do you have to have minimum numbers of healthcare workers to man those beds. It is usually not the physical number of beds that is the limiting factor, it is the number of nurses needed to open those beds.

The number of patients that a nurse can cover for a shift is based on something called acuity, if a patient is an Intensive Therapy Unit (ITU) patient they would normally have 1:1 nursing, if the patients are less unwell a single nurse may care for 4 patients. Nursing numbers are based on standard acuity, if suddenly your ward is full with higher acuity patients you can’t magic the extra nurses you need out of thin air. In my world, the world of children and young peoples’ healthcare, then staff numbers are even more important. We have young babies that not only need healthcare, but they also need to be held and played with, they are developing not just physically but socially and that is also a caring responsibility. We knew therefore that staffing was going to be our biggest challenge. Not only that but for children there was just so much more about the virus that was unknown, as so many of the cases had been in adults. Viruses rarely behave the same across age groups, it was hard therefore to predict whether this particular virus was going to be more or less severe in children, we just didn’t have the information. This is important as there are actually very few paediatric beds in the country, especially paediatric intensive care beds. We’ll talk about why children aren’t just small adults more later but even from a basic perspective, kids are different, you need different beds, you need different sizes of needles, tubed and other equipment, and so you can’t just switch an adult bed. So, for our hospital and my team, this was going to be a big challenge.

Trying to find a way to test staff and patients became crucial, we were still in winter after all, and so many other respiratory viruses were still circulating. It’s probably worth talking a little bit about how test development normally works. First, to detect a virus by polymerase chain reaction, more commonly known as PCR, you need to know what the genetic code of that virus is. This was tricky as although the labs in China were sequencing the virus, they also had quite a lot of their own sickness and their own demands to manage. In the early days we were all desperately reaching out to our colleagues, contacts and networks trying to get hold of the viral sequence, the chain of A, T, C and G’s that would allow us to start testing and finding out what was happening in our staff and patients. Once you have the sequence you then design what are known as ‘primers’ – complementary pieces of DNA that will bind onto your unique target and permit you to then replicate or amplify your viral target so you can detect if it’s there, even in low levels. Even this was different compared to normal, as there are only a few companies and manufacturing facilities that could make them, and suddenly everyone across the country wanted them at the same time. There were many late night phone calls and chasing emails just to make sure that your order would be delivered. You would have thought therefore that this was the most complicated bit, this in itself would normally take several months to design and then make sure that it worked efficiently. For SARS CoV2 however we managed this part in under a week, which required so many people to pull together.

The challenge was made harder as you need positive material in order to be able to both validate (check it works) and to act as a control (ensure it is still working) every time you run the test. We had a test (sometimes called an assay) but in February we just didn’t have any control material, we knew it worked in principle but sadly you don’t know the assay really works until you start getting positives and you can’t get positives until you have an assay that works. We are so lucky in the UK to have amazing scientists who stepped up and worked with international colleagues to be able to get us the material we needed to be able to start testing locally. Over 3 years on, the idea of not having any virus available seems bitterly laughable, as I now have freezers full, but back then it was a real barrier to getting everything up and running. Ironically, in the early days of the pandemic, we needed more people to be getting sick and having positive tests before we could get access to enough virus to be sure our testing worked, never mind getting enough information to help with the still distant possibility of vaccine development.

There’s probably something I should mention here, I have a history of not dealing with viruses well, especially respiratory viruses. I’ve been hospitalised on a number of occasions, and I spend every winter basically moving from one illness to the next. The irony of working in IPC and yet physically not being able to manage my own infections is not lost on me. I also have family with autoimmune conditions which mean they also don’t respond well to infection. As the situation progressed in Spring 2020, therefore there was another layer to how I was feeling about the information I was seeing and what I was dealing with. I began to lose the differentiation between the Dr and the person. Usually when I am dealing with incidents at work you are able to walk away. No matter how bad the day is, no matter what you have dealt with, you can walk away and go home put on a movie, snuggle down with a cup of tea or a martini and switch off. This wasn’t like that. I was working in an environment that potentially put me at higher risk of exposure and then carrying that risk home with me to someone who could be potentially significantly harmed by it.

Not only that but having been ventilated due to a respiratory virus previously I knew that every day I was rolling the dice with my own personal health and well being. There was no separation of identities, I eventually just became Dr Cloutman-Green all the time. It was the only way to control the fear and to be honest it was all anyone wanted to speak to anyway. Friend, family, they all wanted to have the latest updates and the latest advice and so the only conversations became about SARS CoV2. There was no switching off, there was no stepping away, there was only the pandemic, decision making and risk control.

By the time we reached the 20th March 2020 the situation had become real enough that I wrote and sent a Letter of Intent, in lieu of a will to a couple of my friends to hold in case anything were to happen to me. I wish I could say that in hindsight I felt that had been an unnecessary step but between then and October 2020 too many people I knew and some I cared for deeply died and so it was probably one of the most sensible moves I made. From March onwards there was definitely a sense of change, a growing understanding of what was now on our doorstep and how life would be forever changed.

People fall into 2 main camps when reacting to scenarios like this, where it’s becoming apparent that significant change is afoot, one camp fall into complete denial and the other immediately believe the world is going to end and everyone will die. The reality of this scenario, like so many others, is that the truth is somewhere in-between. Working in IPC is about being comfortable living in the grey and working with ever changing information. That’s not a place that many people feel comfortable. I became increasingly aware that we were very bad at communicating and educating about what being in this place of shifting sands means.

Messages from the government and media are all about communicating with certainty and reassurance. Is it any wonder therefore that people lose faith if they are told that something is definitely A on day one and then on day 7 they are told that it definitely B instead, with little or no explanation about how that shift occurs? I am often not the media’s favourite guest as they want to talk about a topic they have chosen and the answer must be yes or no. This was very much the case during this stage of the pandemic. People were scared and the media and other sources wanted to respond to that fear by giving certainty, but frankly there wasn’t any. Instead of having the more complex conversation, instead of trying to educate and support the public so that they had the skills to assess the information that was coming out, everything was simplified into single issues that could be communicated with a 30 second sound bite.

I felt it was increasingly important to step up to the plate (see, I can even sports metaphor) and do my bit to ensure that the science and information being communicated was as accurate and balanced as possible. I’ve spent years going into schools, universities and different public forums to talk about healthcare science and IPC but this was something really different. There was so much need from the public but there was also a lot of political implication and the media and others had interest in telling particular aspects or taking particular approaches. It was therefore quite a scary thing in terms of putting your head above the parapet in case there was a backlash, either personal or professional. As a scientist it was also very challenging, as you can see from my Facebook post I was in a scenario where every day we were learning, every day the information was changing and the guidance was evolving. Normally when I offer expertise it’s because of precisely that, I have knowledge and expertise. In 2020 none of us had the clinical expertise to provide the full picture, what was often asked was that you be a source of comfort and definite answers in a world where everything was changing rapidly. Something that in good conscience I couldn’t provide, all I could do was tell it how it was at the moment I was on the radio/in front of a camera.

I had gradually moved from the person who posted in January, saying I wouldn’t speak to the media as I had no evidence, to the person in March onwards who felt obliged to talk to the media precisely because we had no evidence. At this point in time there were so many academics who had never worked in clinical labs or in hospitals sitting in studios and talking to the public about how they saw the world. Sadly, this was often in a way that wasn’t really reflective of what was going on or even helpful. I remember very clearly sitting in a studio for Saturday morning radio with LBC trying to smile at my fellow expert whilst wearing enormous headphones that weighed down my head, feeling exhausted after weeks of extreme stress and very little sleep whilst he, an academic virologist, talked and talked about his book on viral pandemics and thinking ‘he has no idea what it’s like’. He hadn’t made the choice to continue going in and working despite personal risk and not knowing what would happen, he had never worked till the last tube was due to go because you can’t close down your computer and leave patients if everything hasn’t been done, and they certainly had no experience of trying to make diagnostic testing work in a lab that was already stretched to capacity when you can no longer order swabs or reagents as there is now a global shortage as suddenly everyone needs the same equipment to be able to test their patients. What they were interested in was selling a few more copies of their book and sounding smart for the clip that they could play to their colleague.

The reality for me was that every piece of information that got out there that wasn’t truly reflective of the situation, that drove people to their extremes made it more and more difficult for me to manage my day job. There were those people who reacted to fear by putting their head in the sand and dismissing all of the information coming out as inconsistent because it was ever changing and we weren’t putting it in context. The ones that listened to the commentary that said it was ‘just like flu’ and not a big deal. This meant that we had people who wouldn’t do what we were asking, who wouldn’t declare symptoms, who just didn’t want to know because they didn’t acknowledge the risks. The other side of that coin were the people who had been driven to the extreme by fear and believed that we weren’t doing enough or were hiding things from them because the situation was worse than was being communicated. These people were cancelling clinical appointments that were really needed because they weren’t convinced enough was being done, I even had staff doing things like buying and wearing disposable rain ponchos as they didn’t believe the personal protective equipment we were issuing was sufficient. Much of this was driven by the way information is communicated, but not just that, it was driven by the way we communicate about science. Instead of science and scientists being there to help people understand risk and supporting personal judgement by enabling conversations about different situations, having different solutions, both the way we educate and talk about science, leads us to being invited onto public platforms to give an answer, a one size fits all solution.

I did what I could to be the person who sat on shows, who posted on social media, who was present enough to say ‘these are the things you need to consider’ ‘these are your options based on your personal circumstances’ and most importantly to say ‘this is the situation as we know it today, but obviously we are finding out new information all the time and so it will change and be updated as we know more’. I became increasingly aware however that if I only communicated at the bequest of other people I would only have the opportunity to speak about the topic they gave to me to in a window they chose. It began to feel more and more important to have a route to speak to the public as openly and as directly as I could, in my voice, in something that was unedited and allowed them access to me as a person as well as a scientist, somewhere I could talk about the good, the bad and the ugly so that people saw the whole picture.

This wasn’t the first time I’d thought about having some way to talk science directly with anyone that was interested. On the 5th of December 2015, I’d started a blog, but after one post, abandoned for lack of time.

“Hello World

So, this is my first ever blog post. Bear with me as I don’t really know what I’m doing. I’m what is known as a Clinical Scientist and I work in Infection Control.”

I posted this just after I finished my PhD but it took a pandemic to enable me to see both the need and the requirement to find a place where I could use my own voice in my own way in order to talk directly to the public without being filtered by what someone else thought should be communicated.

Reviving it now was an act of self-preservation, although I didn’t really know how true this was at the time. I just knew that to get myself and my team through what lay ahead, I had to find a way to hang on to ‘me’. Thus, the Girlymicrobiologist blog was born… Little did I know that as Girlymicro – a blog I wrote that began as professional reflection on some of the technical aspects of working in science, like antimicrobial resistance – would soon grow to encompass…..Formula One, zombies, MeToo, women in science, the women who went before, and terrible personal grief. It would spawn an online community of followers, lead to performances in a zoology museum, the Wellcome Collection, online Stand-Up comedy nights, and the Bloomsbury Festival. It would enable conversations among Healthcare Scientists and the general public over vaccine development, risk assessment and my love of microbes, and incredibly I would receive a New Year’s Honour, a trip to Buckingham Palace in Queen Elizabeth’s final year and an invitation to the Coronation of King Charles III in the first year of his reign.

But all that was in the future. For now, there was the job.

It’s not just about hand washing!

What I do working in IPC is about balance of risk, not definites. It’s about risk assessment. If you stand in a room with a patient with X infection your chance of getting that infection from them is Y. If we do things like wear protective clothing, wash hands or give the patient treatment, the chance of you getting an infection drops. Those measures are always done in groups however and you rarely do any individual action i.e. introduce masks without introducing measures to control the other aspects of transmission. There aren’t studies therefore on what difference an individual measure does or does not make, it would be unethical to do them, I would never normally deliver a lower standard of protection in order to scientifically understand each of them better – my job is to protect everyone after all. So, when called to be on the news or radio and asked a yes or no question I am probably not going to be their favourite guest, as I will pull my favourite impersonation of any politician and try to answer the question with an answer that I want to give, often a story, rarely containing the words yes or no. Working in IPC means living in a world of grey rather than black and white.

So what is working in IPC actually like? Well, when I started working in IPC in 2007 I, like many people, believed that it was all about hand hygiene i.e. cleaning your hands with either alcohol gel or soap and water. Little did I know that it would include: monitoring ventilation and water sources, taking samples for things like chicken pox/measles and now SARS CoV2, laundry contracts, surgical instruments, food hygiene inspections, vaccination programmes, working with occupational health, pest control, Reindeer audits (more on that later) and so much more. Fundamentally, working in IPC is about stopping the spread (transmission) of infection. Sounds simple doesn’t it? Sadly it’s far from simple in practice, 10 plus years in and I’m still learning every single day even now. So why is it so complicated?

Firstly, it’s complicated as there are so many possible ways to become what we call colonised or infected. Colonisation is something seen mainly in bacteria as we need many of the bacteria that exist with us to live, either as they help us produce nutrients, or they occupy a niche that means they stop us being colonised with more pathogenic versions. If you are colonised this means you have an organism present, for example MRSA, but it isn’t currently causing you any harm. As humans we have bacteria present all over our bodies, many parts of our body aren’t sterile i.e. organism free. If you have an organism as part of what we call ‘normal flora’ present that would make an infection more difficult to manage. I will manage you differently as I want to make sure of two things, one that the organism you carry with you doesn’t spread to someone else and two that it doesn’t move from the site where it’s causing you no harm, such as in your nose, to somewhere else like a surgical wound where it could go on to develop as an infection that I would then need to treat and might make your hospital stay longer and mean you take longer to recover. As patients who are colonised have no symptoms we have to specifically search for these organisms, this is called surveillance and means that we might do things such as screening patients on admission in order to better understand their risks. This is different to SARS CoV2 where you don’t become colonised but there is an asymptomatic phase where you are infectious to others but have not yet developed symptoms. Infection on the other hand is where you have organisms present that result in symptoms, leading you to actually feel unwell. Infections therefore more frequently require some for of management, even if this is just taking on fluids and getting plenty of rest, compared to colonisation which doesn’t usually require any intervention.

Having said all of the above every person, every patient is different and therefore it’s crucial to remember that when judging risk and making management decisions. I for instance have been admitted as a patient myself numerous times as my immune system does not deal well with viruses, my risk from a respiratory virus is probably different therefore to that of my husband. Organisms are all around us but the risk they pose to patients is different depending on what is going on with them. A bacteria known as Pseudomonas aeruginosa is frequently found in water and we come into contact with it all the time without it doing us harm, but if you are a patient on a ventilator in a hospital I work really hard to make sure you aren’t exposed as it could get into your lungs and cause pneumonia. Infection risk therefore cannot be separated from people. People also behave in different ways that mean they are exposed to different types of risk, some people backpack through the Andes, some people keep exotic pets and others work in jobs like mine which mean that they may be more at risk of coming into contact with viruses and high risk organisms. Therefore, rather than my science and IPC being all about organisms it is in reality all about people and how they experience the world.

One thing to really bear in mind is that nothing is static, things change all the time. Pre the 1980s no one had heard of MRSA, in the 60s and 70s HIV didn’t exist, prior to the noughties we didn’t have the original SARS CoV and before the 2020’s SARS CoV2 didn’t have a name. Even since starting to write this book we’ve had another pandemic declared in the form of Monkey Pox, by the time this book is published Monkey Pox will likely no longer be the name of the virus. Organisms change, especially RNA viruses which are much more likely to mutate and alter. It’s not just that though, people change as well. When I started working in healthcare conditions that killed patients are now recoverable, genetic conditions are now picked up earlier by neonatal screening and we have new treatments coming online all the time. This means that we have a greater number of patients with chronic conditions that make them susceptible to things like infection not only surviving but being managed in the community rather than in hospitals. Therefore, the group impacted by things like SARS CoV2 is also larger.

Compared to previous global pandemics that everyone has quoted, such as the 1918 flu pandemic, the world is also a different place. We all travel much more than we once did, SARS CoV showed how quickly a virus could therefore move around the world if an outbreak occurs somewhere that has good transport links. Everyday all of us come into contact with large numbers of others. If like me you commute on the tube you will spend time with hundreds of strangers. That means that containment of transmission is very different from these early outbreaks, where individuals were much more likely to know who they had spent time with, concerts with 90,000 plus people are very much a feature of modern life rather than in the past. When the pandemic hit there wasn’t a handbook about how to manage it. I’d been part of plenty of table top exercises looking at how we’d manage a flu pandemic, but SARS CoV2 was different, we didn’t even have a name for the virus when it hit, let alone an idea of how it was transmitted or the best ways to stop it and treat it. We were learning every day, going back to first principles and making our best informed guess, all while the world looked on and judged how we did.

Another thing to remember is that no IPC intervention comes without cost, some financial but a lot of it in terms of individual cost for the sake of the wider good. If I place a patient in isolation in order to minimise their chance of transmitting to others there are consequences for them. Studies have shown that patients who are in isolation (put in single bedrooms) are more likely to experience drug or other errors in care, as there often is only a single member of staff looking after them and so there isn’t someone else present to double check decisions. I know, I know, I think that I would be thrilled to have my own room, the reality is though that if you are in hospital for a long time then having a room on your own can be quite literally an isolating experience. You may see very few other people at a time when you are in need of support and potentially distraction, this can lead to depression as other studies have shown. Even basic things like the requirement for enhanced cleaning can present a problem, this cleaning is easier if patients are on the end of surgical list, for example, this means that they are much more likely to get repeatedly cancelled as theatre list run over time. Impacting waiting times for surgery and over time on patient outcomes. Decision making in IPC is often a fine balance between protecting everyone whilst minimising the harm you could be doing to the individual patients, something that is hard enough when you have evidence and experience, but that’s even harder when you are going into something truly new and undefined.

The day to day of IPC feels like it is something that happened in another life a very long time ago, a new normal has taken over erasing much or what came before. By the time October 2020 rolled around I saw something that finally made me make the leap and start regularly posting on my blog, it made me realise that I needed to change the way that I was talking about the pandemic, COVID-19 and science in general and so I posted:

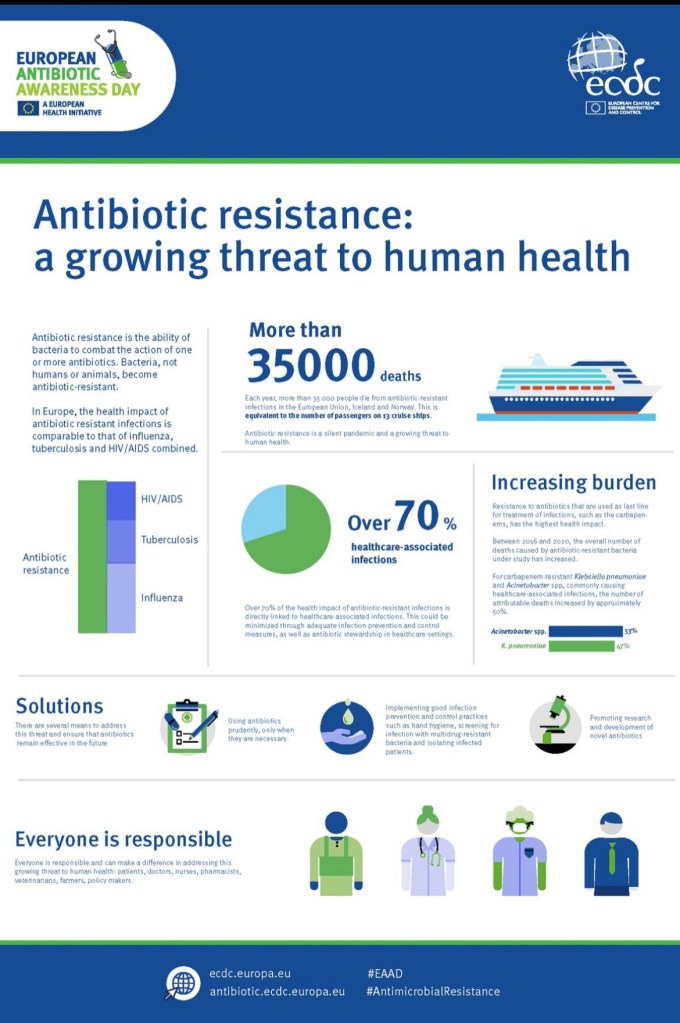

“This week I was going to post about Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) as, in many ways, it has been quite a momentous week in my professional life and it all ties into AMR. I may still… but I wanted to raise something that has been playing on my mind this week in light of the social media reactions I’ve seen to the new COVID-19 (don’t call it a lockdown) tiers.

Let me say now that this isn’t a political post, purely one linked to reflections that have been triggered for me that are linked to some of the pitfalls of traditional communication, medicine and dissemination.

On Wednesday, I saw this tweet from YouGov (16:02 14/10/2020):

‘68% of Britons say they would support a two-week nation-wide ‘circuit breaker’ lockdown at the start of the school half term later this month’

The scientist in me responded with, ‘well of course’ and ‘surely people understand the ramifications for everyone if we don’t find working containment measures.

When I see posts like this, I usually scroll through the comments. I think it’s important to read what people are posting and see what the challenge is like, as it’s all too easy to see the world through the eyes of those in your bubble. Those people in similar situations to us, with similar views to us, who then use stats like this to reinforce the positions we already hold.

Then, as part of the comments, I saw this:

‘68% of people in secure jobs, WFH or on final salary pensions. Pathetic’ and ‘Nail on head. All these commentators, MP’s, scientists, professors, journos tec, not one of them worrying about how to pay their rent/mortgage, feed themselves/their kids, pay their council tax/leccy bill, pay for fuel/phone bill. Easy to call from your ivory tower innit’

My first reaction to this post was to blow out my cheeks and sigh. “The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few” and all that. That’s an economic problem that should be addressed, not an infection issue: think of the number of people who will die etc.

Then I stopped and realised there is truth to this

I do live in an Ivory Tower

Now that’s not to say that I am rich, and it’s not to say that my response to the poll is wrong. It is to say that we must reflect and admit the truth to ourselves. I can pay my mortgage. My job is not at risk (although my husband’s may well be). I can buy food and cover my bills. That gives me a privileged position where I can engage with and make decisions about how I feel about the science, the justification, and the way they are implemented. I don’t have to react from a place of worry and fear. That privilege means that I can digest information from a place of logic and not emotion. That privilege also means that I can lose perspective about how others may receive the same information and I certainly have to be aware of that privilege when it comes to judgement.”

From October 2020 onwards the Girlymicrobiologist blog became something that I not just used to communicate, but something that frankly I used to help me survive. It meant that I had a way of reflecting that made me better at my job. It helped me manage during the pandemic whilst I lost family members, whilst I lost colleagues and whilst I made the tough calls that at some points felt they would come every day and might never stop. It helped me have a voice when even friends decided to lash out against scientific advice and other family members were on social media breaking the very rules set out to protect them, whilst I lived in fear of what would happen if I got sick. More than all of that it also enabled me to find my joy when times were dark, to find the humorous side of some of the madness and to feel less alone by seeing the responses and the reads rack up. It really was the best of times when I saw how people came together to achieve what we had believed to be unmanageable.

IPC had found it’s place on the international stage and I had found my voice. I had no idea how important those things would be to surviving the next 2 years and how fragile they both were.

And that’s it. Chapter 1 is done. Chapter 2 and a full book submission are also done, and I’m slowly going to send it out to those who might be interested.

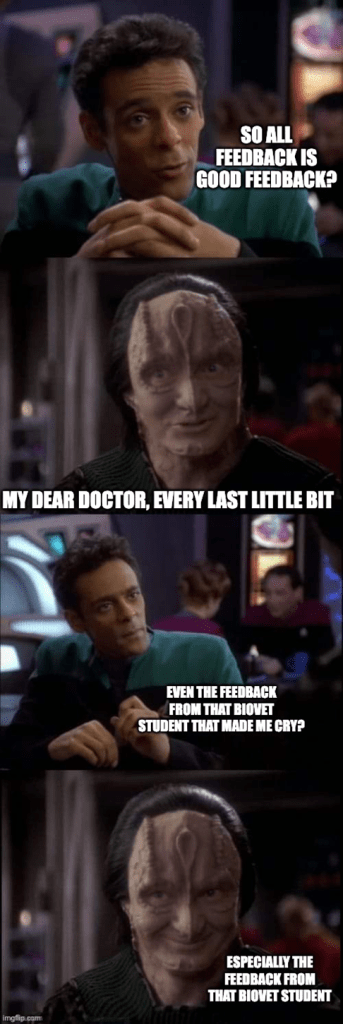

I am super happy to receive all constructive feedback and any thoughts about where I should think about sending it to……..or thoughts on self-publishing. If you think it’s dead in the water, you can also tell me this, but you must simultaneously send gin!

All opinions in this blog are my own