This week we are lucky enough to have a wonderful guest blog from Nicola Baldwin. Nicola is a playwright and scriptwriter, Royal Literary Fund fellow and a Visiting Fellow at UCL, and co-director of The Nosocomial Project with Dr Elaine Cloutman-Green.

https://www.nicolabaldwin.work/

https://www.nosocomial.online/

Where Is Everybody? Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) in the time of pandemic

As a regular reader and devoted fan of Girlymicro’s excellent blog, writing a guest post is exciting and daunting. The project I’m going to consider was a collaboration with Girlymicro, Sue Lee, and – as you’ll hear – many other people. But these reflections are my own.

In February 2020, I stood in front of assembled Healthcare Scientists and researchers at the Precision AMR launch as PPI Coordinator, and enthused over the workshops, discussions, and Festival of public events which would be available to the 25+ research teams participating in this initiative. Within a month, the UK entered lockdown, universities closed to all but Covid research, public buildings lay empty. PPE no longer represented ‘public and patient engagement’ but preventing human contact and keeping yourself and your patients alive. But our project’s funding was time-limited, its purpose was important, and the genuine need to communicate and raise awareness of AMR central to its aims.

Thus began a two-year adventure in the strange new world of PPPI – Pandemic Public and Patient Involvement.

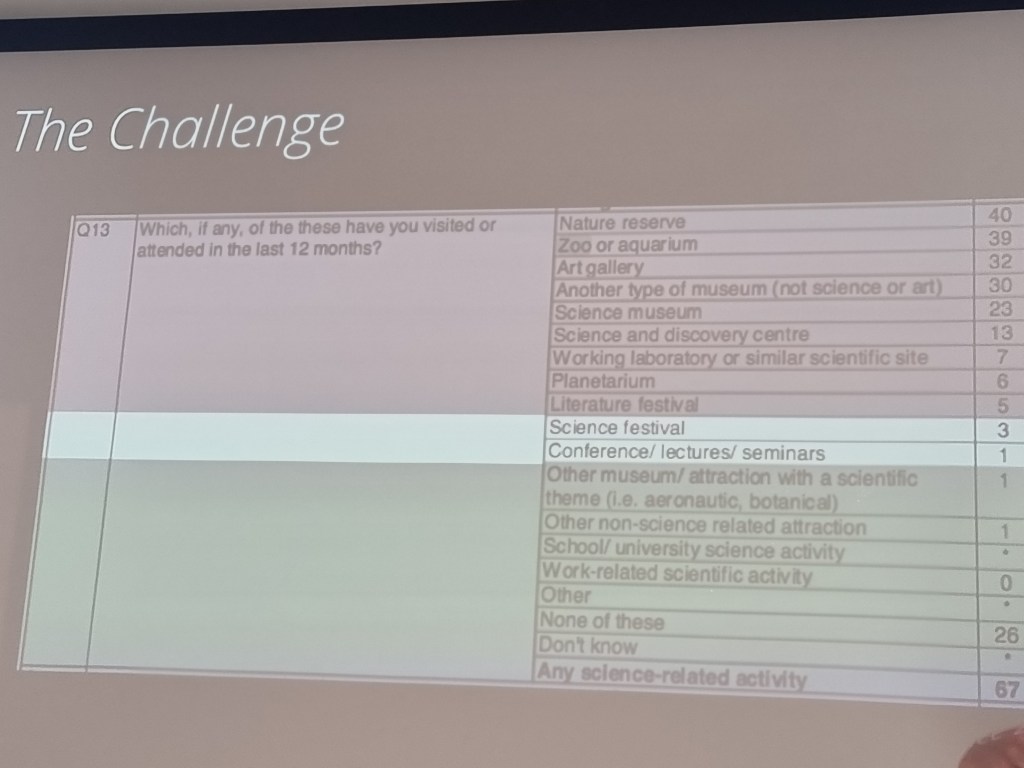

Defining the challenge

After a 4-month hiatus in which seed-funding application deadline and start date were paused, it was time to review our PPI strategy, factoring in the following changes:

- No face to face workshops

- No patient groups

- No contact at all with patients

- No science fairs, school visits, open days or usual channels for PPI

- No public spaces or performance venues

- Many research teams couldn’t start their projects owing to labs, personnel or priorities being reallocated

On top of which…

- No one wants to hear about another looming global health crisis during a pandemic

During the delayed start, I began trialling our ‘message’ on AMR informally with friends and contacts who were – like me – non-scientists. I discovered that – like me – none of them understood what AMR was. Explaining antimicrobial resistance enough to discuss it, was a 2 or 3 stage process something like this….

Friend: I’m pretty sure I’m not antibiotic resistant. I hardly ever take antibiotics

Me: It’s not that you become resistant, it’s the bacteria themselves

Friend: The bacteria? Are you sure?

Me (nodding): The bugs that cause infection after you have a tooth out, or an operation, become resistant to the antimicrobials prescribed to treat them

Friend: Ok, so from now on, I won’t take antimicrobials, just regular antibiotics

Me: They’re the same. And bugs learn to resist them over time.

Friend: So if I have a tooth out, or an operation in future…?

Me: It might take a longer to find a treatment that works, or in a worst case –

Friend: (interrupting) THAT’S TERRIBLE! HOW COME NOBODY TOLD US!

Our PPI strategy needed to enable this conversation, over and over, for each new person to absorb what AMR is, and what it might mean for them before any other targeted messaging about antibiotic stewardship or behaviour change could happen.

This forced me to rethink what PPI means. Involving patients and public in research should be more than a tick-box exercise or add-on. It’s about encouraging public and patients to invest time understanding your processes and objectives. When scientists take part in public open days and fairs, they don’t just demonstrate experiments, they demonstrate enthusiasm; talking about their work, inviting participation, sharing ideas – all of which engages patients and public to invest time in understanding.

I’m a playwright. When I began this PPI project, I was an inaugural Creative Fellow at UCL exploring how drama could build new audiences for academic research. There’s a misconception that as a playwright, your medium is words; really, your medium is the audience. Someone once described it as ‘cooking the room’. Every action, every line of dialogue, every kiss, secret or betrayal, every silent pause or heartfelt song is there to raise or lower the emotional temperature in the room and effect a response in the audience; to involve them, make them care.

Designing a strategy

Given the obstacles outlined about, we needed a PPI strategy which could:

- Be received remotely

- Be engaging enough to spark conversations around AMR without us being present

- Provide a PPI legacy that would have value after the project

- Encourage and equip researchers to create their own digital PPI

We decided to focus on short films. We commissioned actors, writers and filmmakers with an interest in Healthcare Science and encouraged collaborations between scientists working on AMR with artists who could involve the public emotionally. Some of these artists were, or had been, patients potentially impacted by AMR.

And we discovered that, having been forced to micro-manage our overall PPI strategy, we could be more …strategic, by commissioning artists and film makers with knowledge and experience of areas such as migration and migrant health, homelessness, negotiating the health system as a mother without a UK support network, practical experience of working with puppets, or Under 5s. We started the artist films first to encourage researchers to make films, and to relieve the PPI pressure on Healthcare Scientists and researchers who were facing increased clinical or academic workloads during the pandemic.

Over time, another aim was added to the PPI strategy:

- To actively support researchers, by offering regular contact time

The drop-ins were small, tending to attract only 1- 5 people, but the researchers who went on to not only make short thesis films but present work in person and/ or perform in the festival, all came through these sessions. In hindsight we should have started these sooner.

Sue Lee and I ran a weekly lunchtime drop-in session on zoom for any Precision AMR researchers to discuss their PPI, their micro-thesis films, or talk about their projects. This reminded us that the benefits of conversation and involvement which PPI enables, work both ways. Taking part in a science fair or going on a school visit, reminds Healthcare Scientists why they loved this stuff in the first place. Enthusiasm is rekindled. PPI involves you more closely with your research.

Reviewing our results

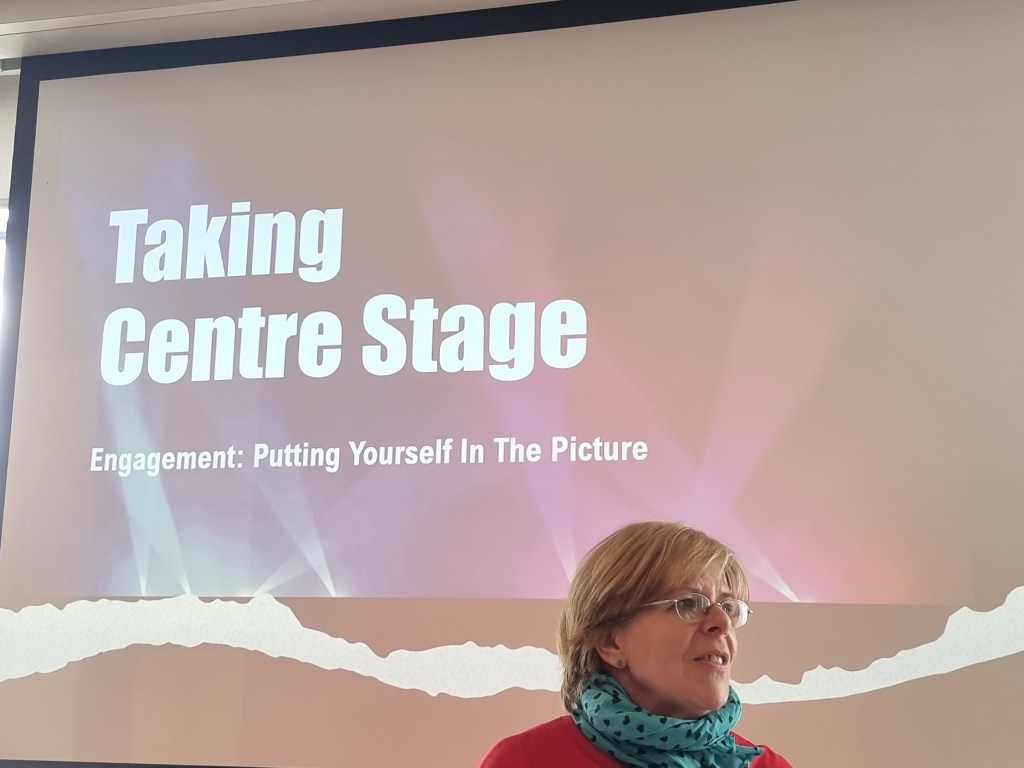

Looking back almost 2 years, we did everything we promised, albeit in radically different ways. In fact, we did rather more than we originally intended. We hosted a series of live public engagement events, screenings and discussions in not one, but two, festivals:

- Rise of the Resistance 1, June 2021, online

- Rise of the Resistance 2, September 2021, livestreamed from Bloomsbury Theatre

- 4 Workshops for Seed Project Awardees on PPI training

- 12 films by artists, 13 films by scientists, 4 zoom debates, three Q&As, a filmed tour and numerous zoom conversations and related video clips

- 500 people engaged directly with festival events online or in person

- PPI participants reported significant changes in their understanding of AMR

- Requests for Rise of the Resistance links and AMR content received from Hospital Trusts, charities, schools and nurseries for staff, patients, and pupils, including timetabled activities for 2022

My personal highlights? Our interactive AMR puppet show for Under 5s, Sock The Puppet performed by Stephanie Houtman (‘Peppa’ from Peppa Pig Live) receiving videos and photos from children of their Sock puppets, or them explaining AMR; Peter Clements’ incredible drag creation / film Klebsiella – both hilarious and 100% scientifically accurate; Rahila Gupta’s La Biotique, an aria from Puccini’s opera La Boheme which updated Mimi from a seamstress in 1830s Paris dying of incurable TB, to a migrant textile worker in the streets of London’s East End in 2022. Each appealed to different audiences and drew them into the AMR conversation. What Is AMR and What Can We Do About It? a show interweaving dramatic scenes, monologues, and Precision AMR research presentations, performed by a combined company of scientists and actors, succeeded in both raising awareness of AMR, and involving audiences in understanding new research – using gold nano-particles, targeted testing, combatting bacteria in hospital showers – which Precision AMR was supporting.

In Conclusion…?

Having got to the end of the last two years, we are only at the beginning – of a longer conversation with public and patients on AMR, and a global research and stewardship response. Undertaking PPI during a pandemic has made me understand what PPI really is. And how it takes time, planning, effort and commitment on all sides to make involvement happen. It is hard work.

Healthcare Scientists wanting to add a PPI component to their project for the first time really benefit from individual support throughout the process. Public engagement and PPI employ a distinct set of skills for planning and delivery, but ‘cooking the room’ has many similarities with doing an experiment. PPI – especially in a pandemic – asks much of us, but in return offers new insights, new contacts, increased confidence, a sense of personal achievement, and occasionally, amazement at what everyone has achieved.

All opinions on this blog are my own