Today is a bit different, today is about celebrating all of who we are and what we bring to everything we do. Friday was also the day for Healthcare Science Education 2024 (#HCSEd24) which was conveniently titled ‘Embracing your authenticity’. As I know that not everyone could make it I thought it might be useful to share what the sessions contained. To do this, the organising team have come together to each blog about their key take aways from each session. So grab yourself a cup of tea and have a read, and hopefully you will finish reading this post as inspired and as happy as the day made me.

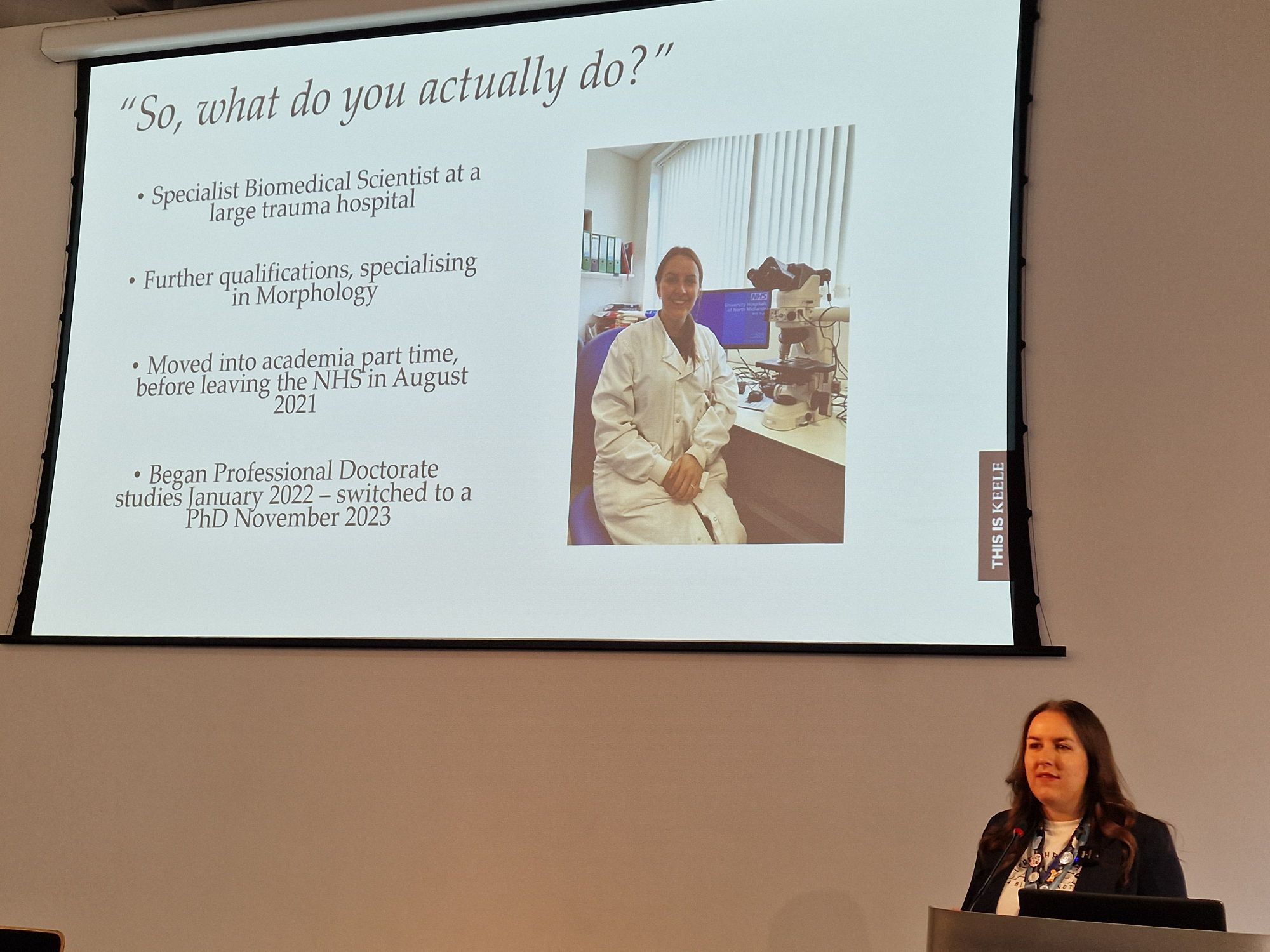

Barriers and facilitators in Healthcare Science careers – Aimee Pinnington (Keele University)

Aimee gave a superb talk covering her diverse career pathway, from her experience as a Biomedical Scientist to transferring to a professional doctorate. Despite a long list of achievements, unfortunately there was a lack of support from the department, building in barriers. After a move to a teaching fellowship, this lack of support continued, with additional barriers becoming apparent. This prompted a further move to a full time lectureship, Aimee began her PhD looking at how to improve biomedical science as a profession and empower the workforce.

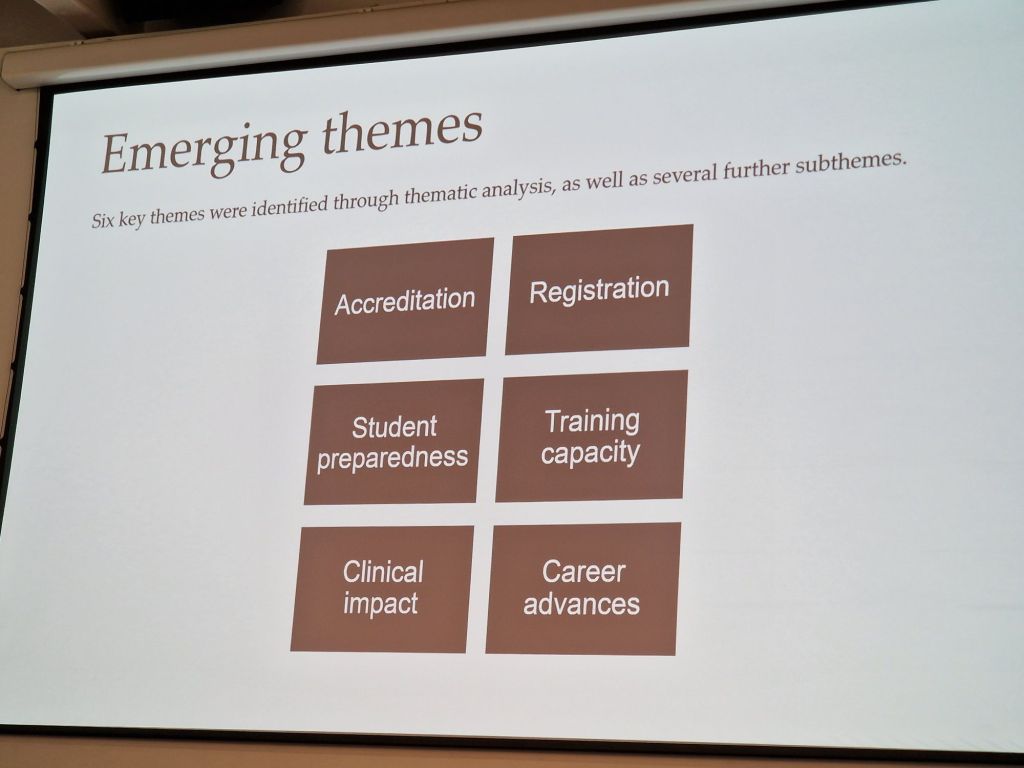

Her PhD research focuses on the impact Biomedical Scientists have on the patient, with there being a lack of direct evidence on the quantifiable impact on diagnostic pathways on patient outcomes. Furthermore, a lack of training posts and placement opportunities can hamper progression. There is further ambiguity of how to progress through the Biomedical Scientist profession to advanced roles. Her research has so far highlighted accreditation, registration, student preparedness, training capacity, clinical impact and career advances as key area of importance to the profession as part of focus groups.

Her research has focused on career advances in the biomedical science profession, which when done well and encouraged, can benefit all areas of the profession and support students entering clinical laboratories. To address this, the project is looking deeper into investigating behavioural traits that impact career progression. Are the opportunities clearly available? Do staff members feel empowered within their departments to take on opportunities for progression? It is also important to consider how barriers to progression change as someone moves through the profession, looking at how a trainee may feel compared to a more senior staff member.

Getting the room actively engaged in the session, a poll identified management support as a key barrier when done poorly, and excellent facilitator for progression when done well. One comment stated how there can be an expectation from managers for staff to progress, without actively facilitating this progression.

Blogged by Sam Watkin

The students dilemma: how to reduce bias in student peer and self-assessments – Dr Neil Holden (University of Lincoln)

Neil brings a fresh perspective to the conference with a background of academia and international pharmaceutical industry experience. He’s passionate about what placements can bring to the academic journey. A key theme developing through our talks this morning is finding our barriers and how we can overcome them. Neil has been asked to talk today about authentic assessment and how to engage our students in this work. How we might bring them into the fold of University culture. We need to acknowledge how education is changing and how we can keep up. Neil feels an essential part of this is bringing the students into the process, and learning how they might assess themselves. The view inwards is becoming more important in this modern AI generated world.

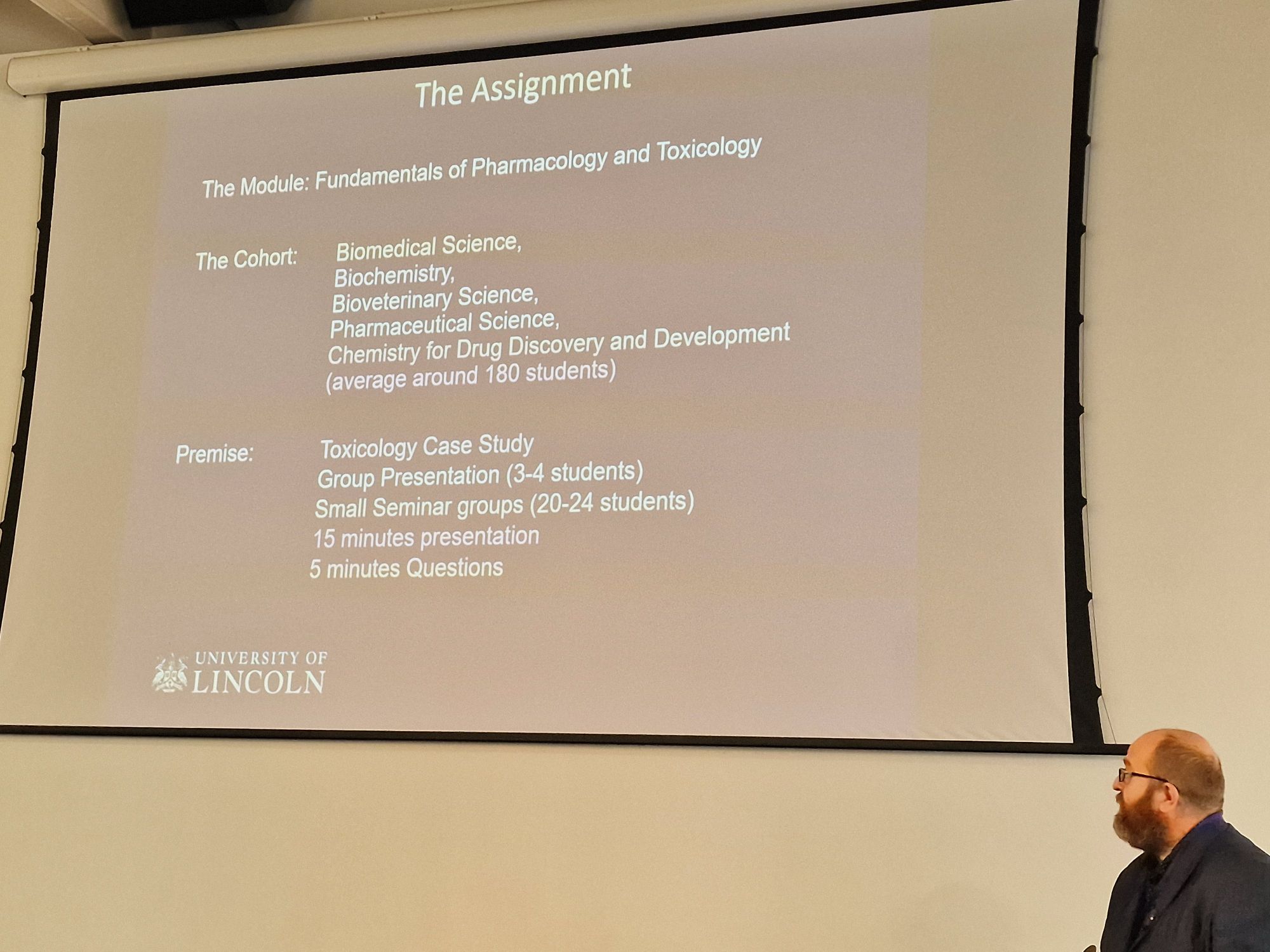

Neil has instigated a peer review assessment in his popular Pharmacology and Toxicology module. Peer review is hugely beneficial – it has enhanced performance, and it massively helps with social skills and ownership. It can have greater impacts than even the lecturers feedback, when it is done well. But how can we ensure that it is done well? How do we identify and overcome bias to create an authentic assessment?

Neil’s approach to this covers around 180 students per year from a really wide range of disciplines – Bioveterinary through to Chemistry students. He makes use of real-world toxicology case studies and asks students to work on a group presentation in small seminar groups. Neil walks us through an arsenic poisoning case as an example of the materials the students engage with – it’s surprising just how funny the odd case of poisoning can be (!)

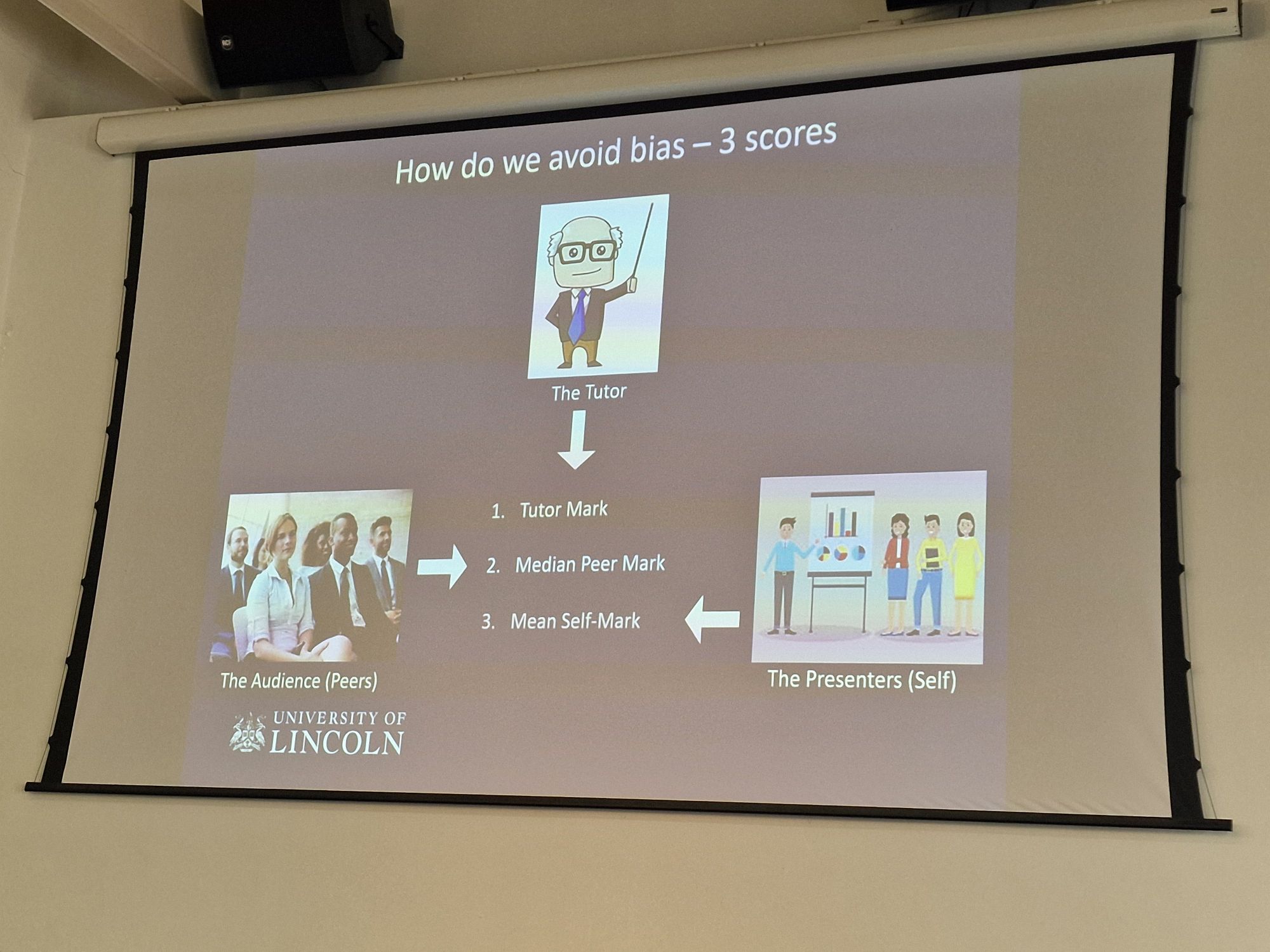

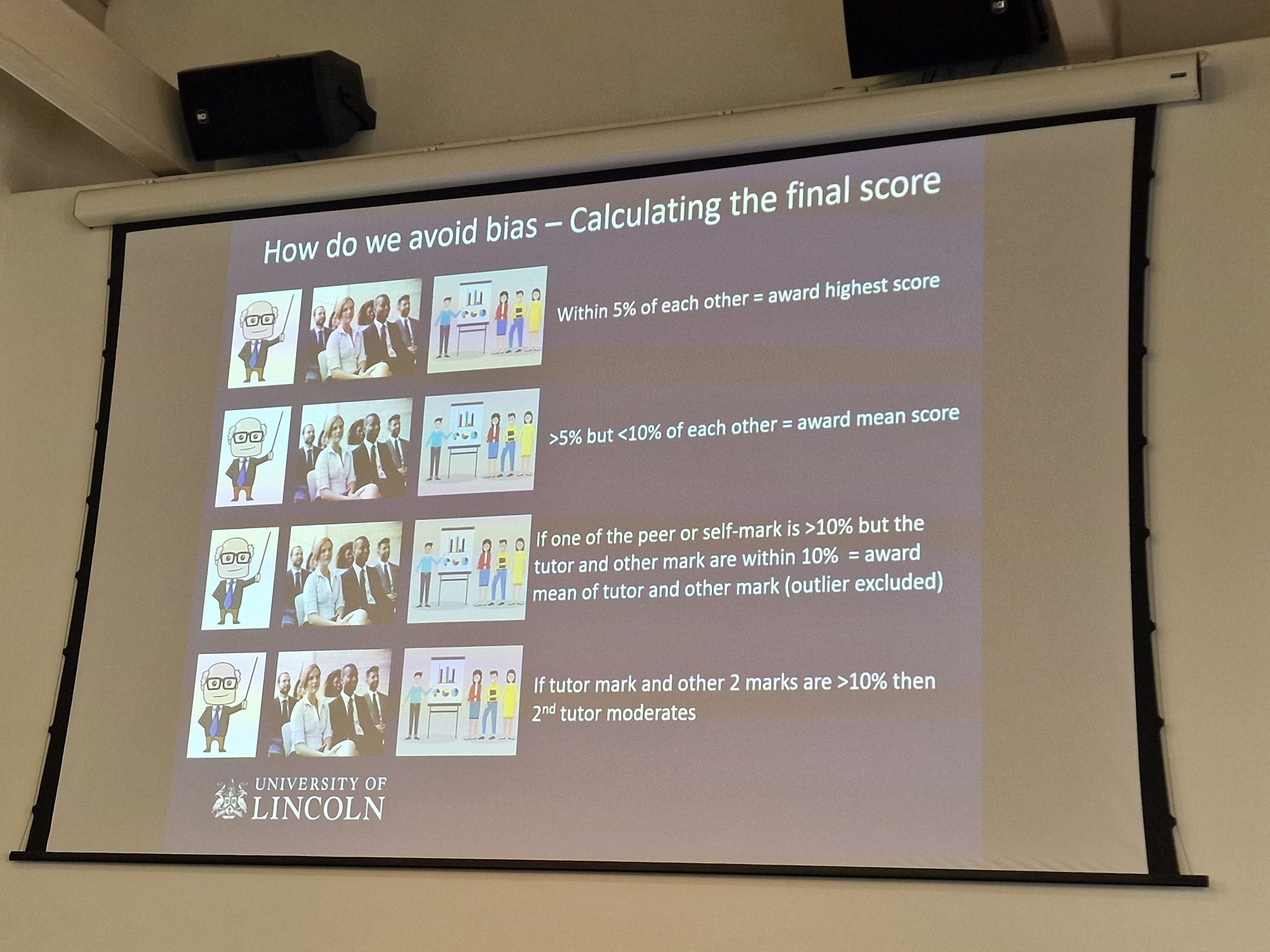

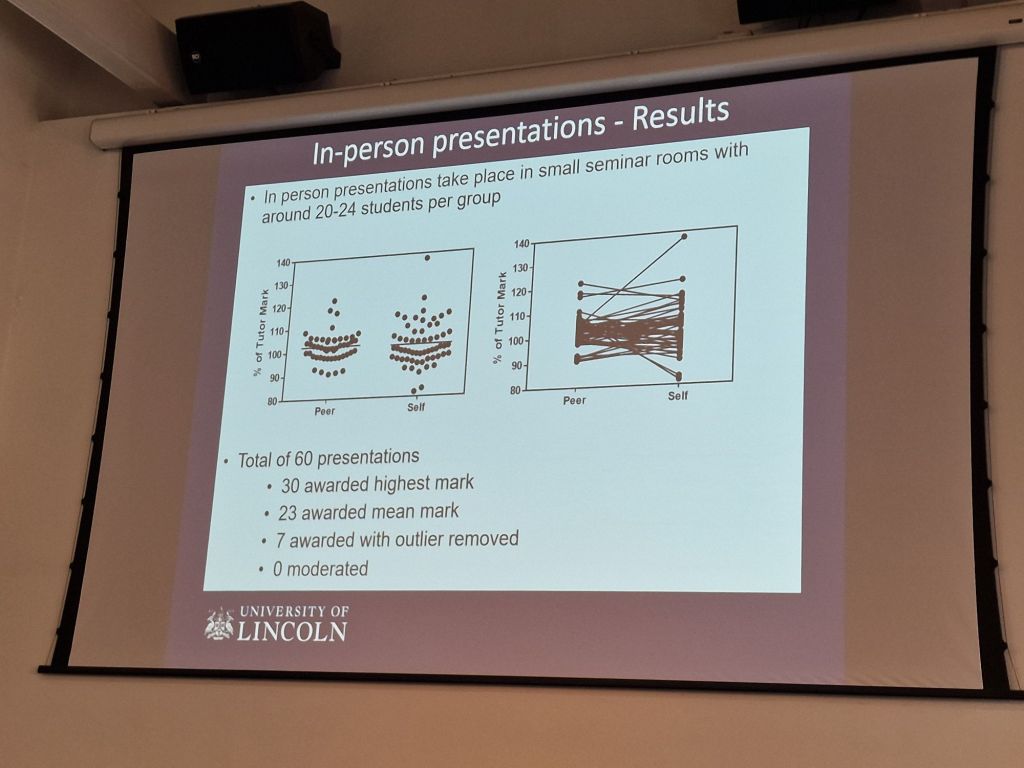

In this approach three different assessors are used; the tutor, their peers and self assessment. They all mark on a number of criteria, with the opportunity to add in constructive peer comments to justify their responses. To avoid bias in the marks the tutor mark, the median peer mark and the student’s self mark are all recorded. Calculation of the final mark is a fairly complex process! If all three marks are within 5% of each other, they get the highest of the three marks. But if they are >5% but lower than 10% they get the average of the three marks. Furthermore, if the self mark is >10% but the tutor and peer marker are within 10%, the mean of the tutor and the peer is awarded. This inventive process really encourages self reflection, and an understanding of the students skills in the difficult area of group presentation. and it works! Last year half the students were within 5% of Neil’s mark, whilst only 7 were awarded with the outlier removed. It’s amazing to see how rarely students are inclined to massively over or under estimate themselves.

Student feedback – they feel engaged, and just about all of them come out of it with a net positive experience. This is a second year module which really helps develop the students skill prior to their third year work. What a nice note to end the final session of the morning on! Authentic assessment leading to such positive benefits to our next generation of pathologists.

Blogged by Dr Claire Walker

Navigating educational comfort zones for impactful teaching – Dr Claire Walker (University of Lincoln)

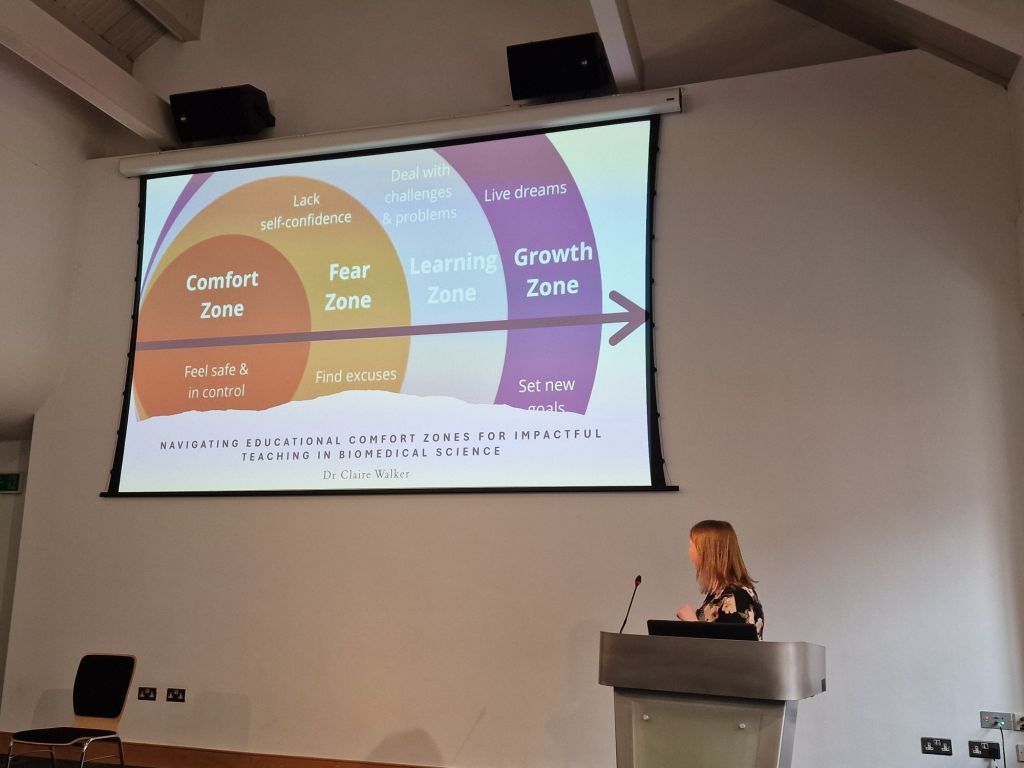

We are all being asked to do more with less, but that means we may need to acknowledge that this will require us to step out of our comfort zone. Comfort zones are about delivery teaching in areas where we feel relaxed and at ease – either linked to topic or style. Many of us who are of a Healthcare Science background feel comfortable delivering 1:1 training or teaching within the lab, this is less possible however if you end up teaching tens or hundreds of students. Claire is a paediatric immunologist, but acknowledges that in her current lecturing role she will only get to give teaching on that topic once a year, all of the rest requires her to become comfortable with stepping out of her preferred teaching area.

Although stepping out of your comfort zone has many benefits, as it expands and supports your learning, that doesn’t stop it being challenging. So how do you create an authentic learning experience? How does this relate to the education and learning that most of us experienced during our training, where most of us learnt from a didactic teaching i.e. standard lecture style, but that often doesn’t work for the topics or students of the day. Claire’s comfort zone is narrative style teaching where she uses stories to communicate, weird wonderful and gross stories, although memorable however it could still be considered didactic. Students love it, but sometimes they find it difficult to tie the stories they remember to the facts that they will need to be able to answer assessments and therefore apply it in practice.

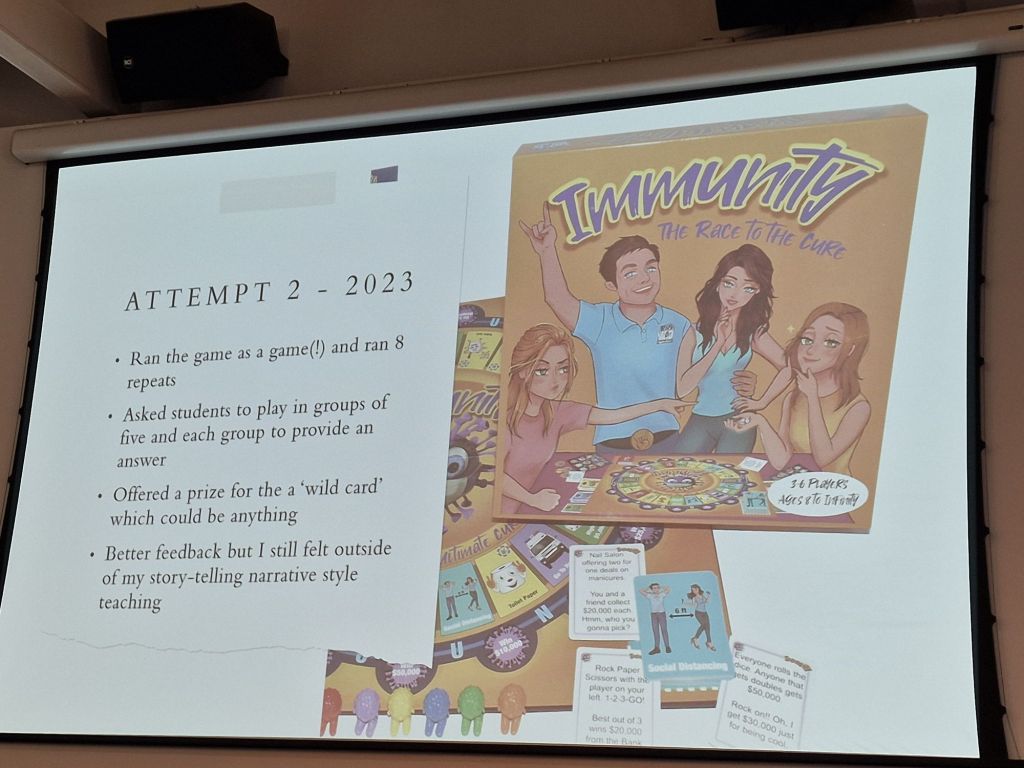

It was suggested by Neil (previous speaker) that it might be worth using an interactive learning approach based on a top trumps style gaming method. It was so out of her comfort zone that when it was first run she ran the game as effectively a lecture, that sat within her comfort zone, delivering for eight hours with limited engagement. It made her reflect that her comfort was actually impacting on what students’ experience of the session actually was. Some of the student feedback was positive, but some of it included that watching someone passively playing a game was not engaging, or that they felt uncomfortable interacting in big groups, which limited their participation. So, for the same session the next year she acknowledged that it did need to truly change. Therefore Immunity: the race to the cure was born. She made it really clear to students that this was an experiment and tried again. Students fed back that they really like the engagement but also gave extra feedback about how it could improve.

Version 3, Claire changed the way the session was constructed again, and put students much more in control of the session and the game. It vastly improved the student feedback, it improved their comfort and feeling of safety. The students now play the game in order to revise in small groups where they full interact with each other. Although, it still feels out of her comfort zone, the feedback makes it worth it. There is also a shared understanding that this is an iterative process where both Claire and her students need to reflect on the session and improving it, with Claire also focusing on why it felt so uncomfortable in the first place. It’s about expanding your comfort zone, but also about understanding yourself. As part of this process it’s really important to take on the feedback. Growing with that feedback, even if it’s bad, and even if it isn’t pleasant to hear. It is an essential part of any process. Learning to take on what serves you and using it to develop is the best possible approach for both yourself and for those you teach/train.

Blogged by Girlymicro

The London Healthcare Science (HCS) collaborative project – Ant De Souza (Great Ormond Street Hospital)

Anthony De Sousa (Lead Educator for HCS at GOSH) gave a wonderful presentation updating us around the work of London Healthcare Science Education Collaborative Project. This is a consortium of HCS at various London NHS Trusts who have secured funding to provide opportunities for HCS workforce education across NHS sites, with a focus on bringing people together to develop networks and to actively form collaborations. Ant illustrated the impact and reach this approach has had for London HCS.

Ant told us that the collaborative formed in 2018 as a result of a Healthcare Science Education event. Post pandemic it is has provided opportunity to re-engage with each other. He showed how, when viewed through the lends of authenticity, there were four key pillars of authenticity: Self Awareness, Unbiased processing, behaviour, rational orientation.

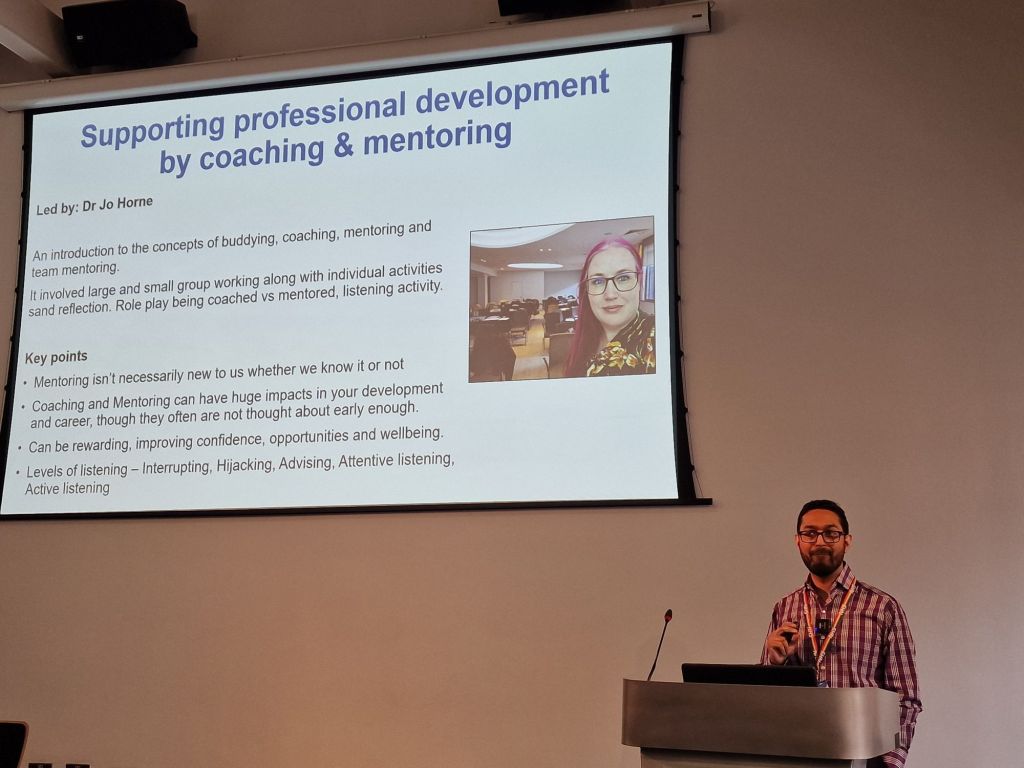

The first event was led by Dr Jo Horne where the concepts of buddying, coaching and mentoring (team mentoring) were introduced. There was small and large group working, alongside individual activities and reflection and listening activities. Ant showed that the learners feedback was overwhelmingly positive. He also discussed how many HCS have never been exposed to mentoring or coaching.

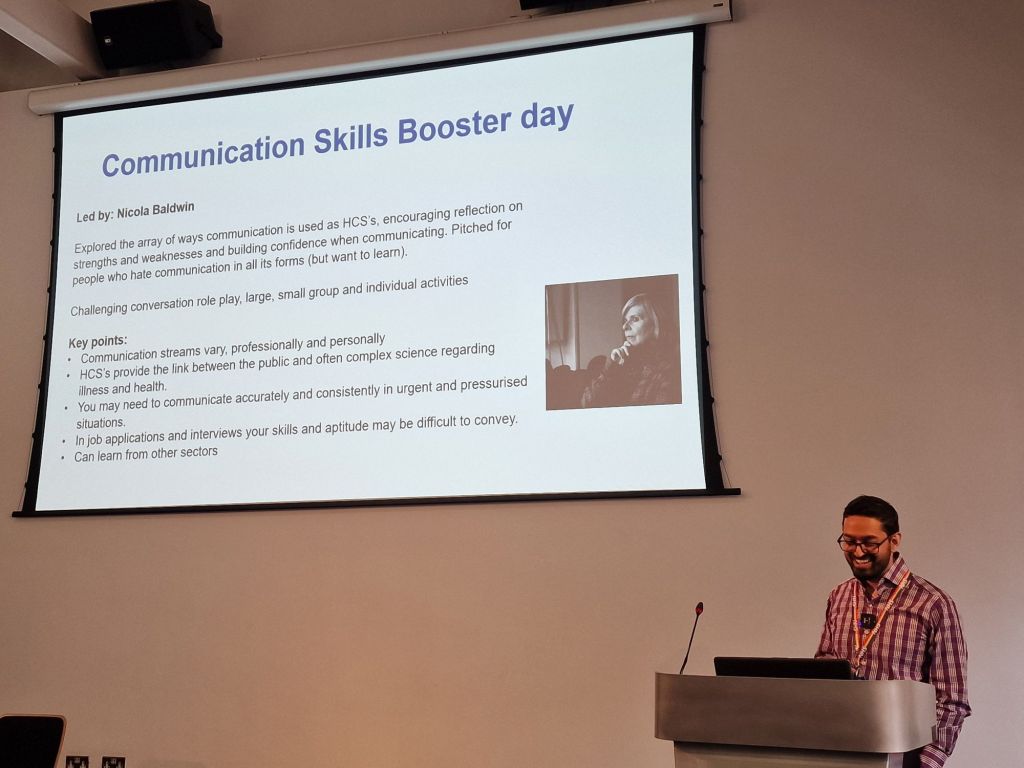

Event two was led by a playwrite called Nicola Baldwin. Nicola explored ways of communicating, encouraging reflection on strengths and weaknesses, and building confidence when communicating in all its forms. Challenging role play was utilised alongside small/large group and individual activities. The key points from learner feedback was that HCS already communicate in different ways in different situations but had never reflected on this and understanding how those decisions were made. Overwhelmingly, learners felt reassured that others were in similar situations with in difficult communicative arenas.

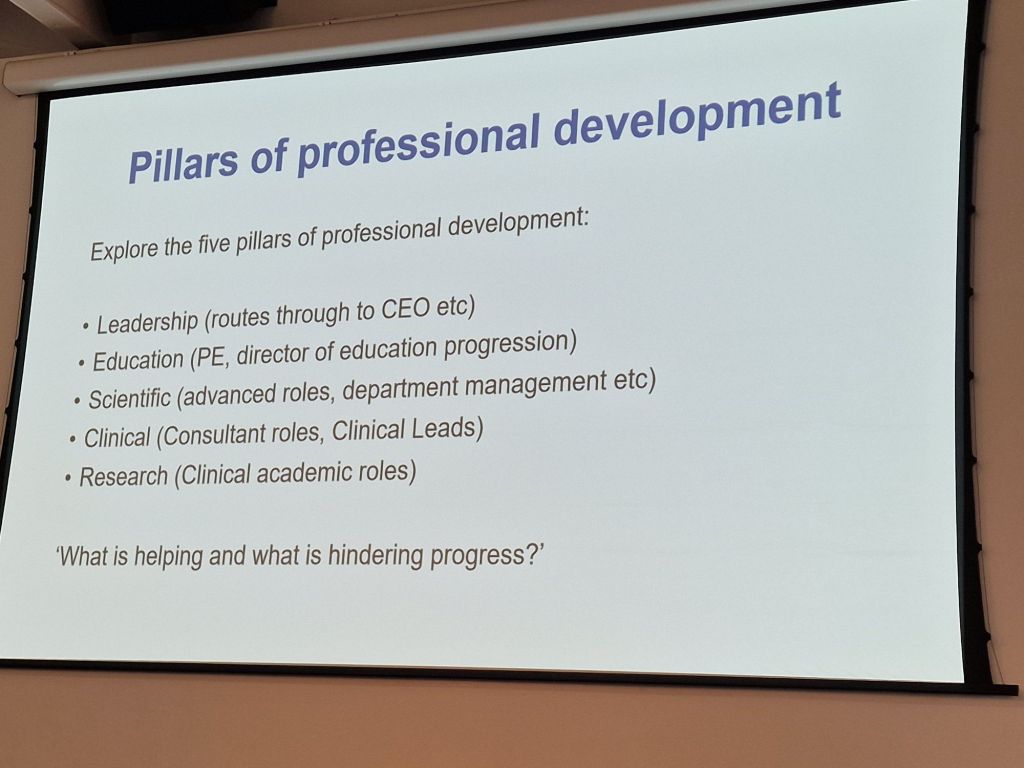

Event three focused on the pillars of professional development:

- Leadership

- Education

- Scientific

- Clinical

- Research

Key points included:

- Senior staff wanted more strategic leadership, educational development and inter-professional education

- Juniors wanted sessions on career pathway progression, technical and digital skills, resulting and analytical skills

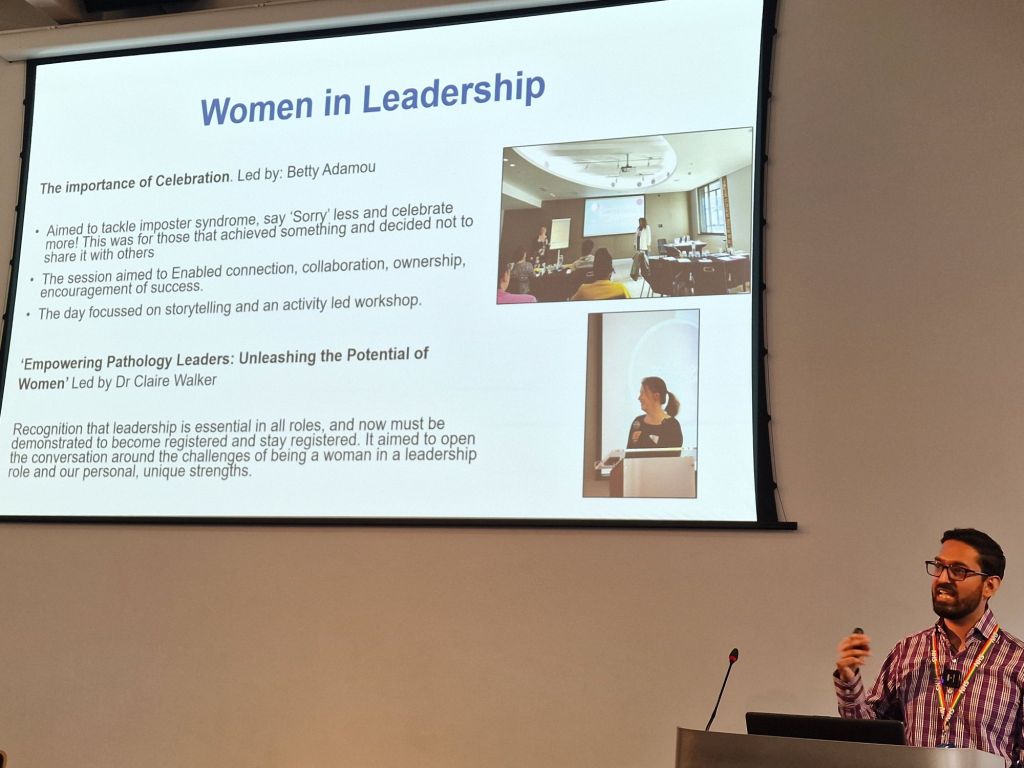

Event 4 on women in leadership was led by Betty Adamou and Dr Claire Walker. This session aimed to tackle impostor syndrome, encouraging women to say sorry less and to celebrate more. Sessions aimed to enable connection, collaboration, ownership, and encouragement of success. Ant shared that learners at this event felt empowered and had never encountered a celebratory event like this before.

Ant summarised the benefits felt by HCS learners who attended all the events:

- Self-awareness – learners worked out how they react, what their values are, and how not to work against themselves (Johari Window)

- Unbiased processing – learners were able to objectively self-assess without blame or denial. He showed how attendees learned to hold themselves to accountability and to not to get in their own way and filter out noise

- Behaviour – Learners explored their values and if they were crossed how they would react. They learned how to be aware of the way they are reacting

- Rational Orientation – attendees learned how to develop close relationships & have difficult conversations.

Ant summarised that learner feedback during these sessions indicated that they:

- Wanted to feel seen and heard

- Valued a sense of belonging

- Were seeking connections

- Valued time for self reflection

- Thrived in a supportive space.

Blogged by Dr Stuart Adams

Being authentically us – Dr Jane Freeman and Dr Kerrie Davies (Leeds University)

To close the day we had the incredibly inspiring duo of Jane and Kerrie talking about how we are more than the sum of the professional hats we wear, and why it’s important to acknowledge who we are as people, not just professionals. They also emphasised the importance of giving yourself time and the use of tools to reflect on who you are, both as individuals and leaders. Not just because this is important in allowing you to find your place, but also in order to understand how it might impact how we interact with others. It’s also important to appreciate how much strength there is in diversity and bringing all sorts of different approaches together for the best possible outcomes.

This was such a brilliant way to end the day and to encourage us to think more, strive more and be more. Thank you to everyone who contributed to the day, but also to those who guest blogged today. You guys are the best! We hope you can join us next year for #HCSEd25!

All opinions in this blog are my own