I am currently in the middle of secret project, which I hope to announce more about in late August/early September. I’m really excited about it but it’s taking a bunch of my time. I’m hoping that you will be just as excited when I can share more details. The wonderful Dr Claire Walker is helping me deliver my passion project by curating the Girlymicrobiologist blog for a few weeks. This means that I hope you all enjoy getting some great guest blogs from a range of topics. Girlymicrobiologist is a community, and all of the wonderful authors stepping up, sharing their thoughts and projects, to support me in mine means the world. I hope you enjoy this guest blog series. Drop me a line if you too would be interested in joining this community by writing a guest blog.

Dr Walker is a paid up member of the Dream Team since 2013, token immunologist and occasional defector from the Immunology Mafia. Registered Clinical Scientist in Immunology with a background in genetics (PhD), microbiology and immunology (MSc), biological sciences (mBiolSci), education (PgCert) and indecisiveness (everything else). Now a Senior Lecturer in Immunology at University of Lincoln. She has previously written many great guest blogs for the Girlymicrobiologist, including Simulating Success – Enhancing Biomedical Science Education through Clinical Simulation. This blog was written by a group of her final year students on their experiences of trying to teach differently.

Blog by Yvana, Nicole and Ellie

We were a small group of three final-year Biomedical students—Yvana, Nicole, and Ellie who were brought together by a shared goal to create something useful for other students by us students. In our final year at the University of Lincoln, we were offered the opportunity to work on a collaborative project focused on improving on how ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) is taught to students- a commonly used technique in the immunology department to quantify and detect biological molecules.

Meet the Team

Yvana

Hello, I’m Yvana – Three years ago, I began my journey as a Biomedical Science student at the University of Lincoln. Like many, I was unsure of the exact career path I wanted to follow, but I knew one thing for certain, I was deeply fascinated by diagnostics and disease. Over time, that interest developed into a love for laboratory work, especially when I had the opportunity to experience clinical simulation sessions led by Dr Claire Walker which stood out to me as they offered a taste of what a real-life clinical lab feels like beyond university.

One of the highlights of my third year was engaging in a unique series of laboratory-based activities known as Laboratory Skills, coordinated by Dr Andy Gilbert. These sessions were designed to strengthen our core technical abilities and confidence in the lab through a series of activities covering microbiology to biochemistry!. After completing 6 weeks of lab skills, Dr Andy Gilbert approached me with an exciting opportunity to collaborate with two other students, Nicole and Elle, also led by Dr Claire Walker on a co-creation lab skills project. Our task? To design a step-by-step resource that would deconstruct one of the most widely used techniques in immunology, ELISA – making it easier for students to understand and perform.

Ellie

Hi everyone, my name’s Ellie! I’m 1/3 of the amazing group that have carried out the ELISA workshop, led by students, for students. During my years at the University of Lincoln, I’ve grown to love the fascinating world of microbiology and I’m even going back this September to do a Microbiology Masters! I have really enjoyed my time at Lincoln and part of that is thanks to Andy Gilbert for putting on his extra lab skills sessions, which allowed me and other students to gain that vital extra laboratory knowledge and practice important techniques.

I’ve just finished the final year of my undergraduate Biomedical Science degree and throughout this year I was able to create something incredible. I, Yvana and Nicole, were given the opportunity to collaborate and develop a practical booklet as a building point of the skills needed to carry out an ELISA. The main reason I agreed to take part in this task is that we, as students, do not get many chances to have such a hands-on experience with many complex techniques, like an ELISA, during this degree. Because of this amazing opportunity, we were able to give students across all years at Lincoln the chance to gain more knowledge and extra practice in learning this crucial technique!

Nicole

Hi, I’m Nicole – one of the final-year Biomedical Science students behind this project. Starting at the University of Lincoln, I wasn’t entirely sure which direction I wanted to take within biomedical science. As the course progressed, I enjoyed the hands-on lab work, particularly how it transformed theoretical knowledge into practical application. This became evident in my second year during Laboratory Skills sessions led by Dr. Andy Gilbert. These weekly sessions focused on core techniques like centrifugation, microscopy, and microbiology.

Co-creating the ELISA workshop booklet felt like more than just a project; it was an opportunity to make lab-based learning more accessible and less intimidating. Since ELISA is a technique, we limited experience with as students, developing this protocol felt was crucial. Working with Ellie and Yvana to bring our ideas together was fulfilling. My favourite part was seeing the complete protocol, knowing it would support students to tackle the ELISA confidentially.

Building the booklet

This project was a collaborative effort and not something we did alone- we brought our own strengths together to create the now called ELISA Team (given by Claire Walker herself!). We spent countless hours in the lab, testing and refining each activity to make sure it worked as intended and delivered the essential skills students would need to confidently complete an ELISA in real time. We held regular meetings, worked on it during lectures (sorry Claire and Andy!), and genuinely had a lot of fun creating something meaningful that we hope will support future students just like us.

Under the guidance of Dr Claire Walker and Dr Andy Gilbert, we set out to create a resource that would feel practical, and genuinely useful for students. We didn’t want a booklet created from a lecturer’s perspective of what students might find helpful. We wanted to build something we would have found helpful when we first encountered ELISA, a step-by-step walkthrough from a student’s perspective.

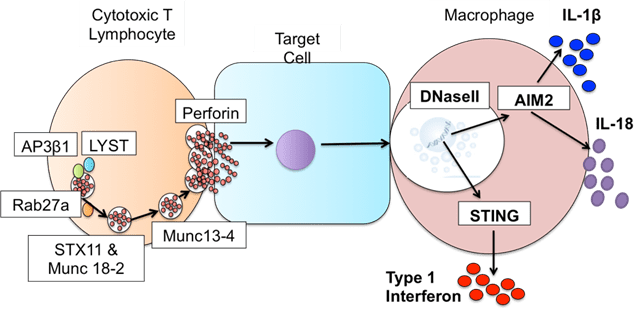

The booklet breaks down ELISA into its fundamental components, from how to properly use a multichannel pipette (which was a nightmare to handle!) to interpreting results and avoiding common mistakes students might fall for. For instance, one key focus was on the washing stages, an often-overlooked step that if done incorrectly, can lead to high background noise and inaccurate results, which in a diagnostic lab can be the difference between a patient receiving an accurate diagnosis or potentially missing one altogether.

What made this project especially rewarding was the opportunity to run our session with real students from first year undergraduates in Biomedical Science to postgraduates in Biotechnology. The feedback we received was overwhelmingly positive. Many said the booklet helped them better understand ELISA both in theory and in practice. We focused heavily on visual learning using diagrams, photos, and annotated guides because we knew from our own experience that clarity and visual support were essential when learning complex lab techniques.

Our final thoughts

Our co-creation project not only gave us a chance to give back to the large community of students, but we were able to bridge a gap that many lectures hadn’t quite managed before, true co-creation between students and lecturers. Together, we created something that students appreciated and benefited from which was entirely made by their peers through mutual experience.

Looking back, we are incredibly proud of what we achieved as a team. It showed us how impactful student-led projects can be when they’re supported by passionate educators and built around supporting the educational needs of the community.

All opinions in this blog are my own