This one’s been on my mind for a while, and by posting it the aim is to explore my thinking, not to target anyone or any group. I’ve been seeing a lot of posts on twitter and having a lot of conversations about identity, especially in relation to professional identity, and so wanted to take this opportunity to reflect and process.

I’m going to start with myself based around a non-clinical example of what I’m talking about. I am a scientist who communicates. I am not a science communicator. It took me an age to really get the difference, but the difference is this………it’s about where my expertise lies. I hope that I happen to be a scientist who has some decent communication skills, and it is a subject that I am pretty passionate about. My qualifications and expertise, however, are in the science, that’s where I sat my exams, that’s where I have almost 20 years of practice. My expertise is in science, not just that, but my real expertise is actually in quite a small subset of science. I took a zoology degree 20 years ago, but I am not a zoologist, that knowledge is old and only at undergraduate level. My expertise is probably in Infection Prevention and Control.

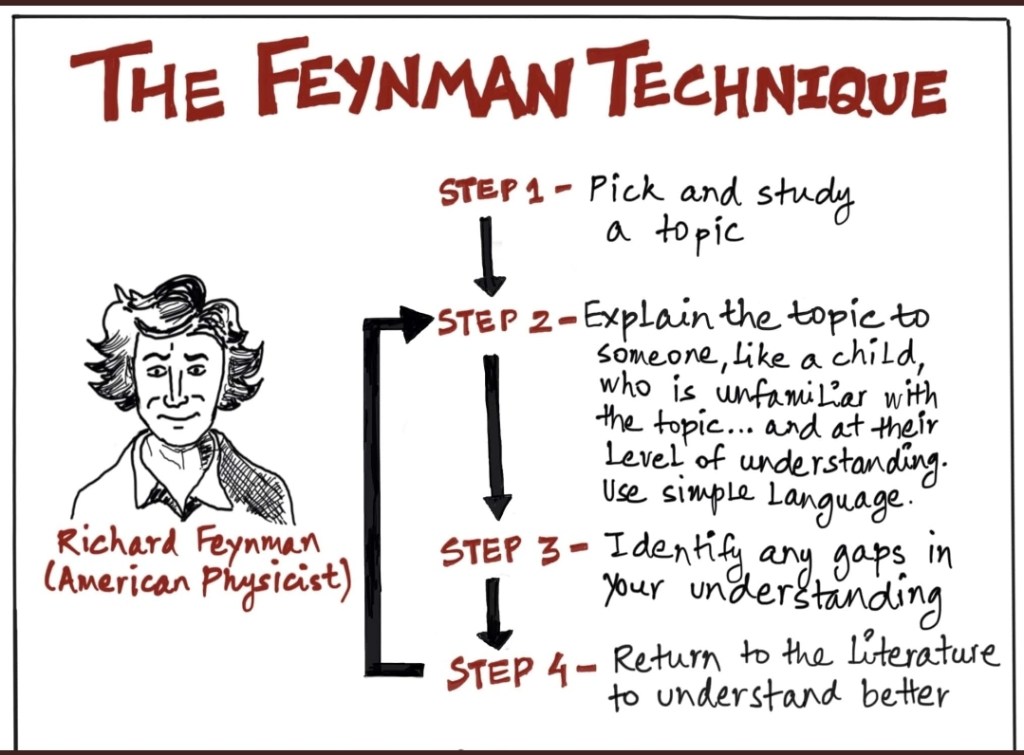

Now, if I were a science communicator, my expertise would be somewhere else. My skills would be around communicating science in general. Many science communicators haven’t worked in science for some time and some may only have undergraduate levels of science specific expertise. What they have, and I don’t, are qualifications and vast levels of experience in communication and pedagogy. These skills enable them to break down highly complex topics and also pitch in a way that I can only aspire to. They have significant levels of pedagogical skills that I can’t pick up by attending a couple of courses, just like they can’t pick up mine by attending a week long course on whole genome sequencing.

So, to me, the difference is where my expertise and knowledge lies. This doesn’t mean that I couldn’t transition from one to the other, but I have to acknowledge that I’d be moving from my area of expertise and therefore would need to rebuild both it and my qualifications to demonstrate skills within a different area. It would be a growth area rather than a straight transition.

OK but why does this matter?

I’ve been reflecting that we are definitely in a period of substantial change within the NHS and one that isn’t likely to stop any time soon. This means a lot of our pathways and traditional professional boundaries are changing with it. I think, in the end, that this can only be a really good thing. (Although I think if it is going to work it needs to be implemented across staff groups with no ivory tower protections). With this change comes fluidity and, because our pathways are embedded, change can occur before we have the processes to keep up.

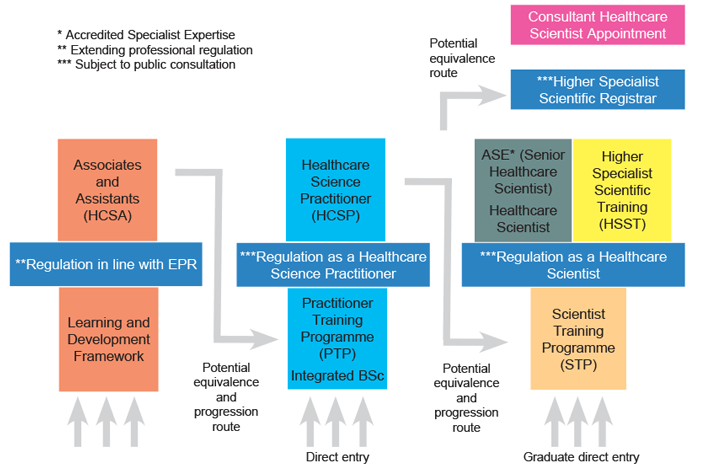

During this period of change and recognition of different skills and pathways, for instance, the HSST, more Healthcare Scientists working in education, IPC becoming more interdisciplinary and the development of Clinical Academic pathways outside of medicine, clarity is key. I’ve been number one in a field of one when I didn’t know anyone else working as I did in IPC and it was a balancing act. I’ve been through people asking ‘are you one of the nurses’ and hanging up if you said no, but also I can’t claim to be a nurse. If we don’t understand our boundaries, it can be hard to be clear about them with others. If we can’t be clear about them with others, assumptions can occur about knowledge and skills that can lead to potentially dangerous practice or misleading those we’re interacting with. To me, it’s about owning your difference and being open to talking about the benefits it brings, whilst being very aware of when you should defer to someone else.

Labels not hierarchy

I guess what I’m talking about is actually the importance of labels. Now, this may seem a little ironic as I’m not a labels and silos kind of girl, but bear with me. The reason we use labels as human beings is that they enable a cognitive shortcut. One of the reasons that they can be bad is that they come with a bunch of assumed information that is not nuanced, and may in fact not be true. In the case of knowledge and professional roles, they come with an expectation that if you say you’re a virologist, you have a significant amount of knowledge about virology and virological processes. If you say you’re a consultant, you will be assumed to be practising at a certain level with certain qualifications behind you. These labels mean that when we interact, assumptions are made about our scope of practice based on an assumed level of knowledge or experience.

The problem with some of the developing pathways is that the information behind those labels is not yet established and embedded widely across the NHS or for the public we’re interacting with. The assumptions made linked to those labels may, therefore, be incorrect. Due to this it is really important to be clear about who we are, our experience, knowledge and boundaries, not because one label is better than the other, but to ensure that all involved have clarity in order to not increase risk. If you are in a new or developing area/role, the onus is therefore on you, to clearly communicate about you practice boundaries in the absence of a default label.

Asking, where is my expertise now?

Everyone wants to feel like they know what they are doing. Everyone likes it when someone comes to them and asks them to engage in events or answer questions due to perceived expertise. The problem comes when we respond to the request based on the pleasant feeling it creates without self-checking if we are the right people to undertake the task.

Obviously, the risks are not always the same and occur on a continuum. I’ve been asked to give talks on antimicrobial stewardship and have referred on to someone else as it was for a conference, and that’s not my area of study. If that request was to teach an undergraduate class, however, I have the knowledge base and experience to do so if there was no one better available. I would however be very open with the organiser that I might be better placed to speak on a different topic. Being clear about your boundaries in a clinical environment obviously holds much greater importance. I have FRCPath and used to regularly do ward rounds. Since the pandemic and moving entirely into IPC, I haven’t given clinical microbiology advice in the same way. This doesn’t mean I couldn’t run a round, but I would want to re-up my skills before I did so, there is a difference between what I could do on paper and what I would feel comfortable to do in practice.

When I interact with others or get requests, I always run a quick internal check with myself about whether I’m the best placed person to respond. There are tasks that are always best served by having input from multiple viewpoints and backgrounds, and these I will bring back so we can discuss them as a team. There are other things where I will refer to someone else specifically, as I know they have a greater understanding of that clinical practice. I’m aware that this all tied into our professional registration, but I am often slightly struck by how, when people are trying to define a new identity, they try to own the label they want before they have fully developed enough to go it solo. I think this is often the moment of greatest risk in any development pathway.

None of this is about restricting access

I want to be clear that I am truly excited by the change towards more dynamic progression in healthcare and recognition of the skills different professions bring to the mix. I do think that when you are already established within a profession, it can be challenging to go back to actively undertaking that gap analysis and flagging your difference all the time, especially when others don’t necessarily know what your role is or react negatively, as we are used to being the ones in the know. The thing is, the only way that you can establish the new pathway or role is to start the work but be mindful to continue to flag your scope/difference as needed. No one hangs up on me anymore when I say I’m not a nurse or a doctor. People have gotten used to it. They wouldn’t, however, if I’d not been open about it in order to engage with the conversation and just defaulted to their expectations.

It is easy to get drawn into the conversations with some conservative colleagues about whether this is the right direction for the NHS to go in and to feel defensive about it. I think that being willing to engage calmly in those conversations is part and parcel of being a pioneer. To see each conversation as a learning opportunity, both for yourself to communicate your role better and for the other person in terms of knowledge exchange. Change is unsettling, especially when it goes against traditional structures and hierarchies, and it will take time for people to adjust.

You can be passionate about something without being an expert in it

Finally, and just one side thought that is not related to clinical work as such. It is OK to have an interest in something and not be an expert in it. It is OK to say for me to say that I’m interested in science communication but not to claim expertise in it. It is OK to be an interested participant and to want to engage in an area because of the growth that engagement offers. You don’t have to enter every space wearing your expertise as a shield. It’s just worth being honest and open with yourself and others when you do it. Not claiming expertise will open doors to shared learning that you might not otherwise be able to access. We don’t always have to be the smartest person in the room. We should just should aim to be the most able to communicate our purpose and vision for being there.

All opinions in this blog are my own