When I was a kid there was a cartoon called Stoppit and Tidyup. It was a kids world where the baddy was the Big Bad I Said NO! This particular post was started during the pandemic when I was thinking about perceptions of the word NO but has kind of lingered as one of those things I wasn’t quite ready to get my head around. The last few weeks have kind of shown me it was still relevant outside of the pandemic however, and so this week I thought I would post about what it feels like to be seen as the gate keeper or to be the person who feels like they are holding the line. In essence, what it feels like to be the person who likes to be liked but who has, as an adult, turned into the villainous Big Bad I Said NO!

I have previously posted about the inevitability of not being liked by everyone, and the challenges of speaking truth to power. The thing that’s unique about becoming the Big Bad I Said No is that it can be a mask/hat/role that is needed in all kinds of settings, and the stakes can vary widely – anything from 1:1 relationships to impacting Trust or wider level decision making. It can therefore feel very stressful to manage, and that stress can be protracted when discussions and scenarios go on for months or longer. Having now spent some time thinking about this though, here are some of my thoughts on the how, whys, and inevitable consequences of saying NO.

Sometimes, it’s all in how you say the words

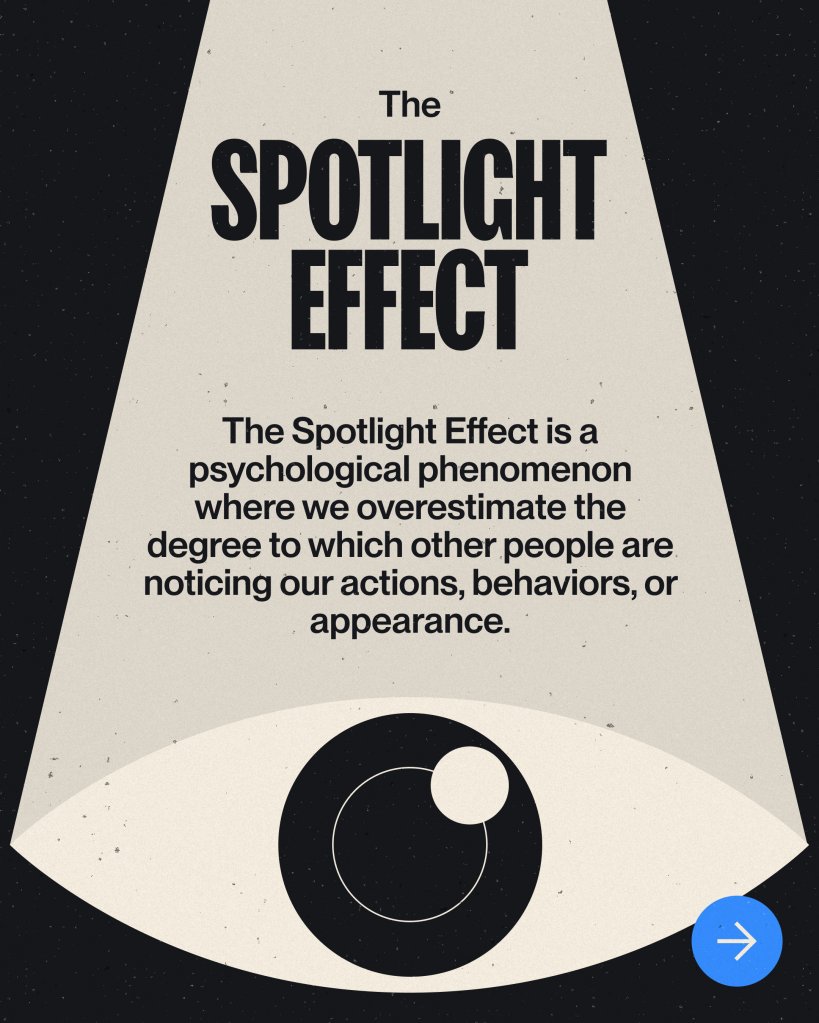

The word NO can feel pretty loaded. The very use of it often brings a feeling of judgement. Worst still, in a world where as leaders we should be trying to bring people with us, it is the ultimate reminder of hierarchy. As a leader, if I have to go there I will just saying NO can make me feel like a failure, as I feel I should have been able to find an alternate solution or compromise. Also, as a previous recipient of NO, it can make you feel powerless and lead to you questioning your understanding of your relationship or the organisational values.

It is crucial therefore, on both sides, to communicate more than just the NO. NO, without an understanding of the values and drivers that led to it can be pretty destructive. So it is important, although the temptation may be to drop the NO and get out of the room, that it comes with context to support the why.

Sometimes, you need to be direct

Sometimes, being a gatekeeper can be pretty uncomfortable. Interestingly, I find it easy with an infection control hat on versus with a Lead Healthcare Scientist hat, probably because patient safety trumps personal feelings. It can be tempting when you are in a position where the NO is going to be hard or challenging to try to say NO without saying NO. The problem with this approach is that although you may leave the encounter feeling less scarred or exposed, it is likely you are also leaving it with less clarity. Worst than this, not only have you said NO, but you also have taken away the recipients’ opportunity to question and gain a clear understanding for their own processing. It may feel easier in the moment, but you are probably just kicking the problem down the line rather than working towards a resolution.

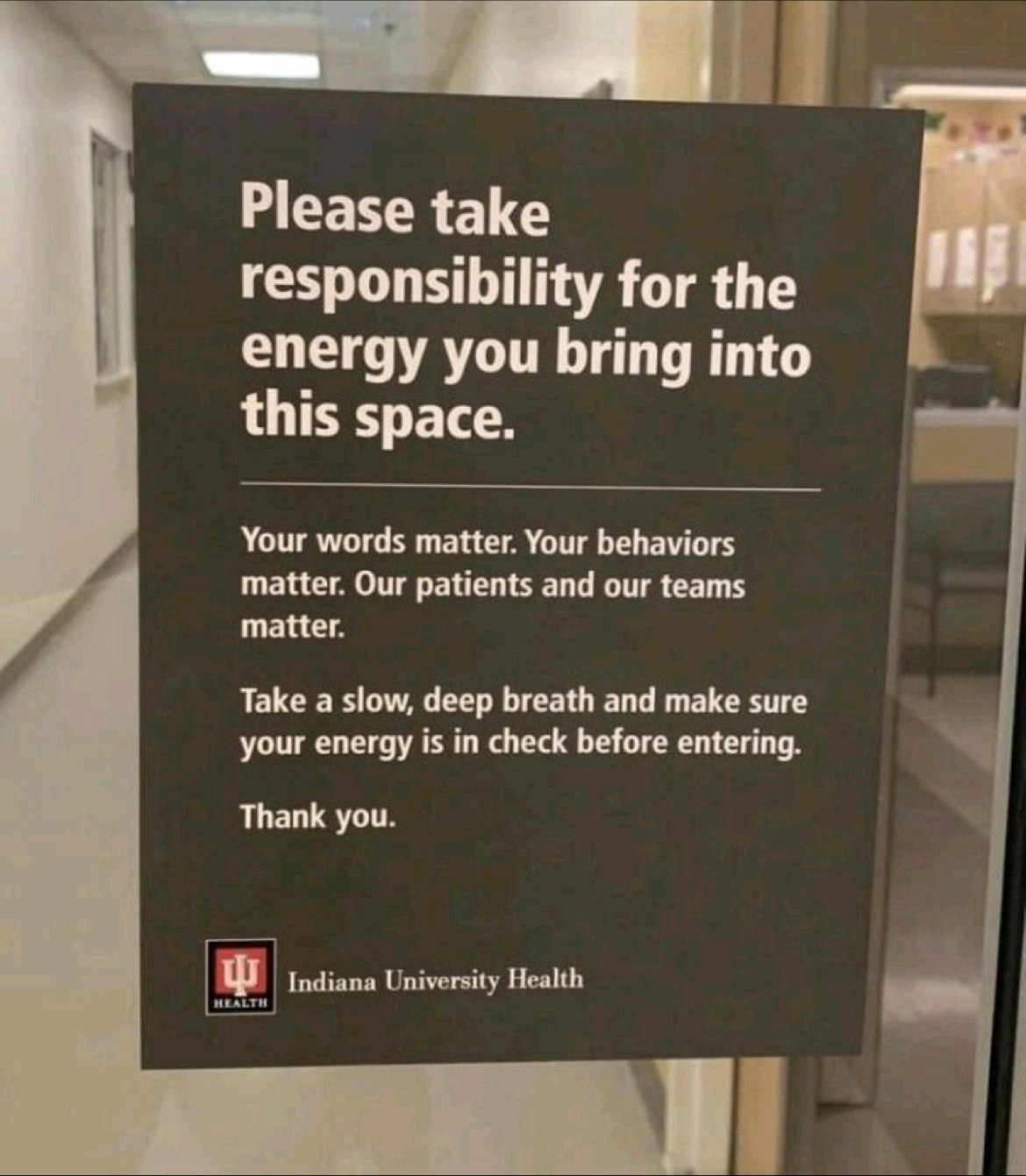

Sometimes, it’s about being clear that you are living your values

I think one of the reasons that a NO and holding the line is easier (although still hard due to the stakes) in infection control is because it so clearly aligns with my core values, and ones that I hope are represented more widely within the NHS. We should all put patient safety first. Therefore, you can respond in a way that you feel enables you to speak to someone else’s shared values. I hope that the same is also true when I speak to people about equity of access, but in truth this one can be more challenging, as sometimes you are asking people to give up something for someone else, this can occasionally overrule this personal value for the recipient.

Sometimes, it’s harder to make that shared value assumption, and so it becomes especially important to share clearly why you are doing something, both from a factual, but also value perspective. This can include things like wanting someone to be in a better prepared position before they undertake training course X so they can get more out of it by starting with a better grounding. It can also be that a change would be better placed after we’ve set it up using pre steps. It’s important, though, that if it is a true NO, not to fall into negotiation, as that can result in confusion.

Sometimes, it’s about showing someone the big picture

Frequently, when I have to say NO, it’s because I have access to information that the other person doesn’t. This may be information that enables me to have a more holistic view of risk or success. When saying NO in these cases it’s crucial to talk someone through that wider picture, not only because it helps them contextualise the NO, but it may enable them to come up with an alternate approach that might result in a YES. I hope that by taking the time to do this it may result in the recipient being empowered when they leave the conversation rather than deflated. Obviously, that’s not always the case, and sometimes, individuals will need time to process the information. At least by investing the time it offers an alternative perspective and hopefully demonstrates that I value both the person and the dialogue.

Sometimes, it’s about showing your thought process

This one is a little bit of an extension of sharing your values and the big picture. In my case, as a scientist however, it also includes sharing data and evidence and using that to explain how I came to my conclusions. I sometimes go too far down this particular rabbit hole, as it’s my comfort zone, and it does not always work.

Some people will respond better to different things. Some people like me respond to evidence, some will respond to patient led and other values, some are pushing a vision, and others will respond if you share the big picture stuff. Knowing who your audience is helps you pitch, but including a bit of everything in your prep and being able to pivot to what is landing best for greater focus is a skill worth developing.

Sometimes, it’s about being prepared to defend whilst maintaining being open

Despite your best efforts to explain and justify, you like me, may end up being pulled into rooms of people who don’t particularly like your conclusion or what you have to say. This is leadership, and particularly in infection control, it’s kind of what we get paid for. Drawing a safety line and holding it is key. Now, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be able to re-evaluate in the face of further information. It also means you should be prepared to defend it. You will need to defend your thought process, your evidence and your conclusions.

I have to be honest, sometimes this is the one I find most challenging. Not because I don’t feel able to justify my process, but when the evidence is clear, I can struggle to understand why others don’t see it. It can also be easy to feel like you’re being personally attacked when it is actually just the scenario. As I wear my heart on my sleeve, I can find it hard though. Trying to take yourself out of the process and focus on the role and the reason you are in the room is something that I’ve found can help.

Sometimes, it’s about finding support

One of the other things I’ve found really helpful is to know where your support lies. In my case, that may be Mr Girlymicro offering me a martini as I walk through the door and telling me it will all be OK. It can be having some trusted colleagues that you talk and walk through your rationale with before meetings. Colleagues that you know may be comfortable challenging you in order to help you see gaps or assumptions in your thought process. Sometimes, it’s about knowing who’s going to be in a particularly difficult room and being aware of where their support may lie, so you know who you may count to support your rationale.

A lot of this is about the work that you need to do ahead of time to build your networks, to get to know other people and their values so you can understand their drivers when you are thrust into a gatekeeping scenario. It can be as simple as moving the dial so you know your unknowns and can therefore better prepare for the unexpected.

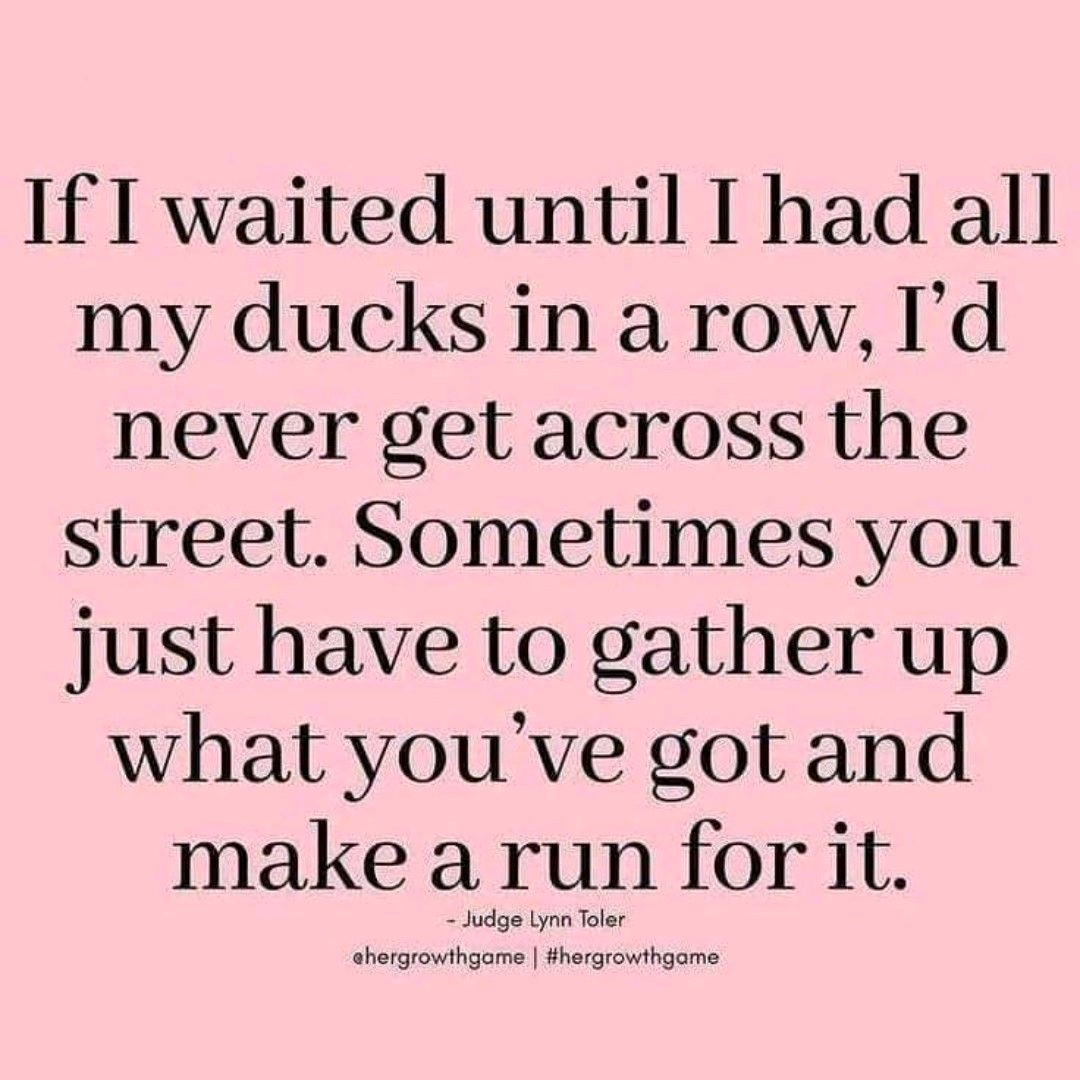

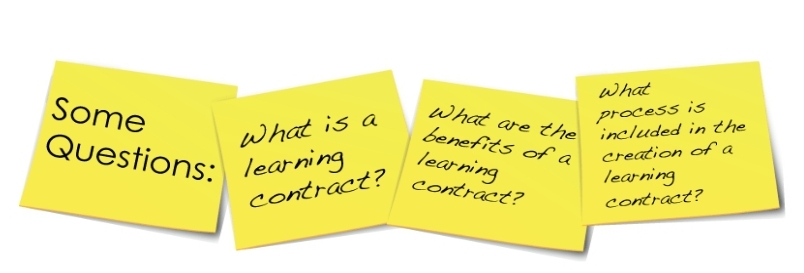

Sometimes, a no is actually a not yet

The other thing that’s worth addressing is knowing when a NO is a not now, or not this way. If you can work your way through a scenario so that you can see different routes or avenues to the same destination, it may open a different type of conversation. I’ve mentioned some of these things above, but again, it’s about having put in the time to think things through prior to your response. Often, in infection control, it is tempting to take the path of least resistance, when with extra resource or input, a YES may be possible. Checking ourselves to ensure our motivations are correct is always worth doing and making sure that we are open to the presentation of new ideas or new information that might impact our risk assessment or evaluation is key.

Sometimes, it’s just about sucking it up

Recent years have convinced me that you don’t join infection control to win popularity awards, hardly anyone gives us chocolates at Christmas. The job is hard. Leadership is hard. Saying NO and gatekeeping is hard. The thing is, we do it because it needs to be done. Sometimes, it needs to be done in order to not set someone up to fail. Sometimes, it needs to be done for safety. Sometimes, it needs to be done for equity across your workforce or because of resource limitations. Every now again, it has to be done because the request is just not that reasonable, and the person making it either hasn’t considered or doesn’t have access to the big picture. Denying it’s hard doesn’t get you anywhere. Denying it’s hard can lead you to avoid the hard moments and therefore dilute your impact. Someone has to be the gatekeeper, especially when it comes to patient safety. Someone has to be the Big Bad I Said NO! Some days, that person is me, and despite it being hard I think that the world is just a little safer for it. So know you are not alone, but when your moment comes, be prepared to put on your big girl pants and own the importance of being the person who both says and owns the fact that they said NO!

All opinions in this blog are my own