Rejection and my ability to deal with it have been on my mind a lot lately. This is because I finally got over myself and started submitting a book proposal linked to this blog and feel like I’ve now become the Bridget Jones of the submission world, overly obsessed with approval and external validation. The thing is only 1 – 2% of books get picked up, which shocked me as it’s even worse than the success for grants, which is about 20%. However, having lived in an academic world filled with rejection for almost 20 years now, it is not like rejection is new to me.

I blogged a bit about the idea of writing a book when I first started playing with the idea, but it’s been a while, and it’s hopefully progressed on a bit. I ummmm’d and ahhhhh’d about keeping the details of this phase to myself, as there is a literal 99% chance of failure, but that doesn’t really align to my values. It’s also caused me to actively reflect on rejection and how I manage it. As rejection is prominent across all areas of science (and life), I hope by talking about my tips for dealing with it, that I can share my learning and support others who may be going through similar things, whatever the source of the rejection.

Acknowledge that failure/rejection hurts and that’s OK

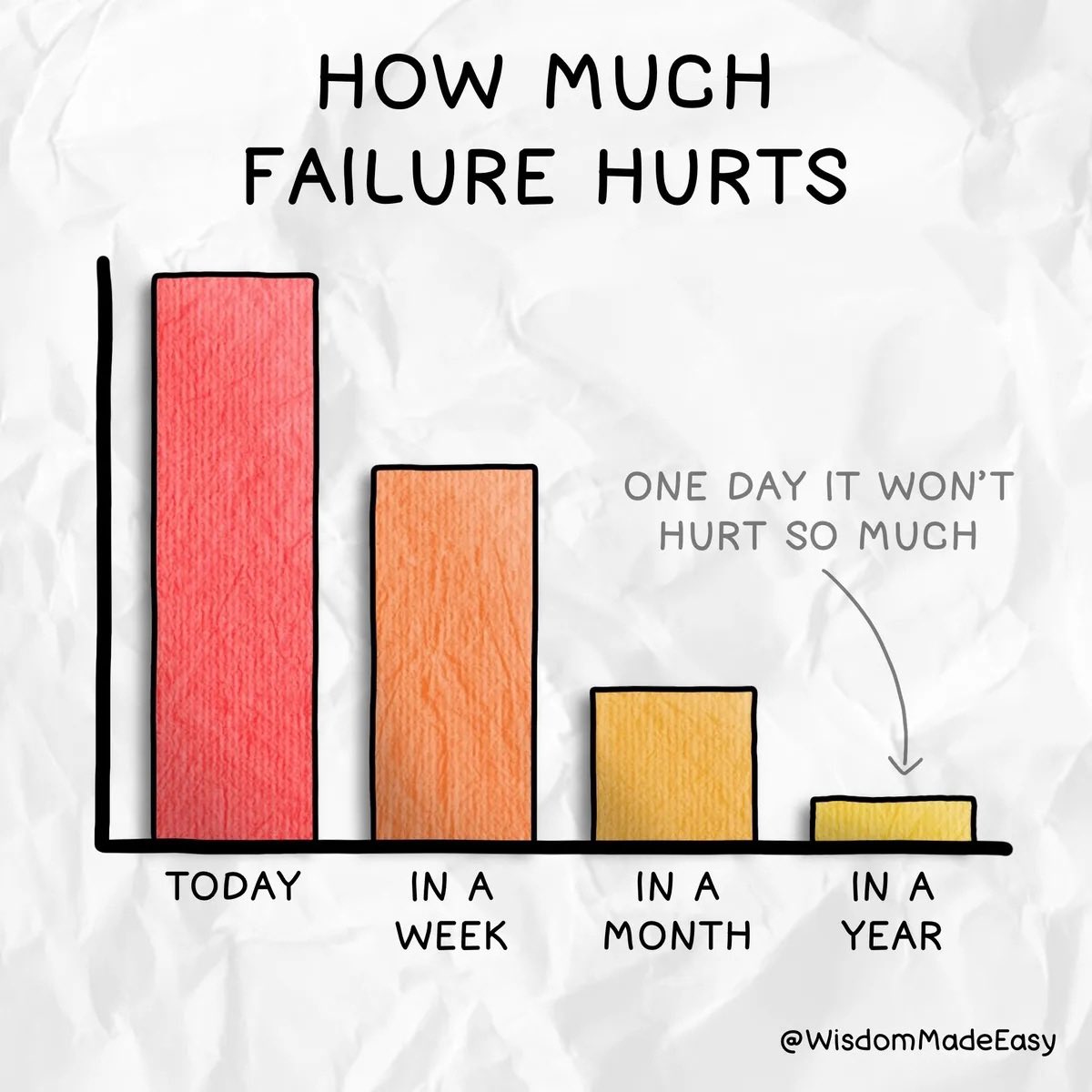

Let’s start by being honest. Failure hurts. It does. There’s no way around it. If it didn’t hurt, so many of us wouldn’t fear it so much. I have begun to think, however, that the reason it hurts as much as it does is because it forces us to have a look in the mirror and reassess, often with increased clarity. It forces introspection upon us, and that can be a challenging thing.

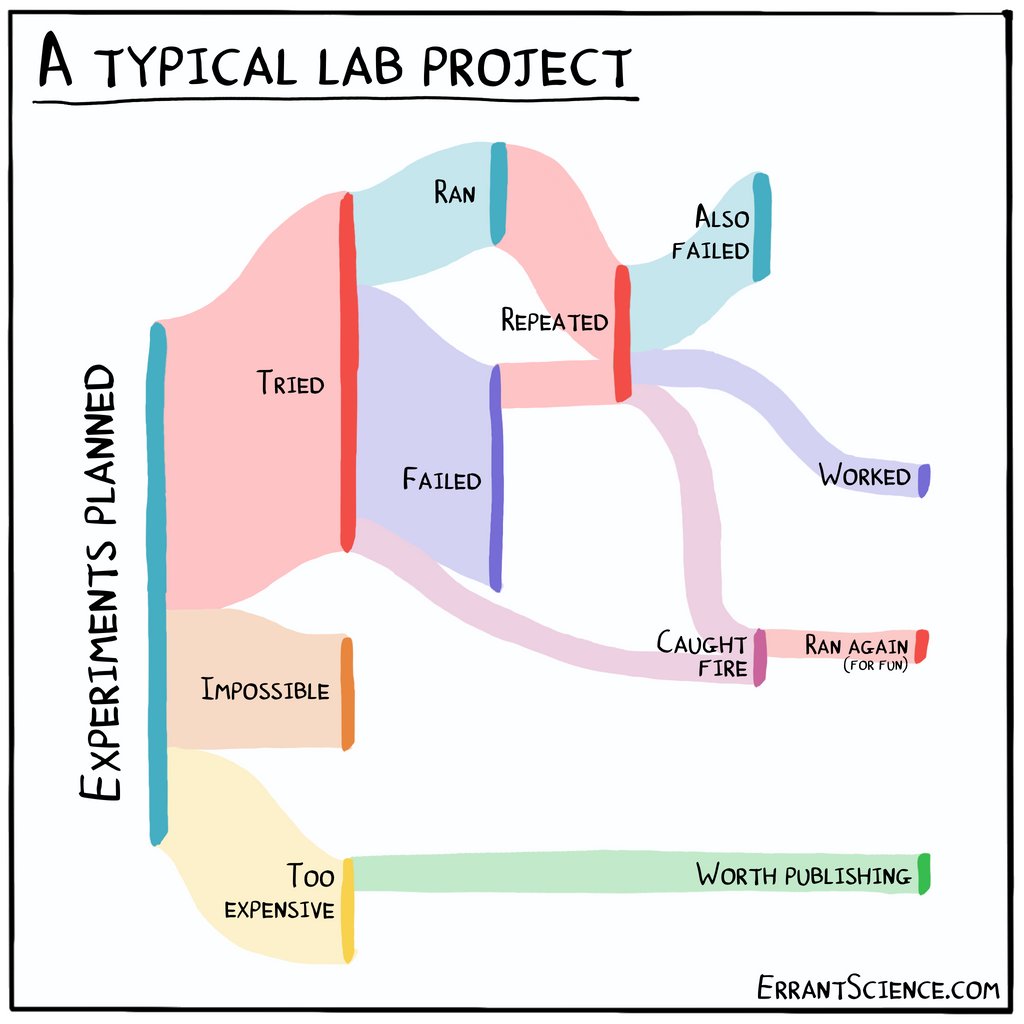

Failure is inevitable however, it’s a key part of the learning process, and the sooner we embrace that inevitability, the better placed we will be to deal with it when it arrives. Developing coping strategies and knowing yourself enough to manage your response is key. For instance, I have 2 key methods. First, I never only have a single plan. Therefore, if grant A is rejected, I will always have hope that grant B is still making its way through the system. Not having all my eggs in one basket keeps me sane. Second, I allow myself an indulgent 48 hour grieving period for failure. I allow myself to feel, to feel disappointed, to move through the self critical emotions without further self critique by forcing denial. 48 hours. That’s it. After that, I move to a more forward focused place. What’s next? What have I learnt? If I try this without the grieving period, I carry it with me, so I’ve learnt I need to move through the emotional aspects before my logical brain can kick in.

Find your support

As I’ve said, failure and rejection hurt, and like other forms of emotional trauma, your recovery is quicker with friends. From going out for cocktails during a breakup, to tea and cake when a paper is rejected, support is key. During the 48 hour grieving period, I may quite frankly need some bitching time. Some time to make the rejection about ‘the system’ rather than myself, to move towards depersonalising the failure. I may also need someone who can point out that the failure is definitely not as bad as it first appears and that the world is, in fact, not actually ending.

Put it into context

The reason the 48-hour grieving period is key for me is because all failure and rejection come with learning opportunities. The challenge is to get to the point where you can make the most of these. For me, I have to move from an emotional headspace to a growth mindset that’s more based in logic in order for this to happen. My emotions and passion drive my creativity, but when out of control, they act as barriers to seeing the big picture and where the learning lies.

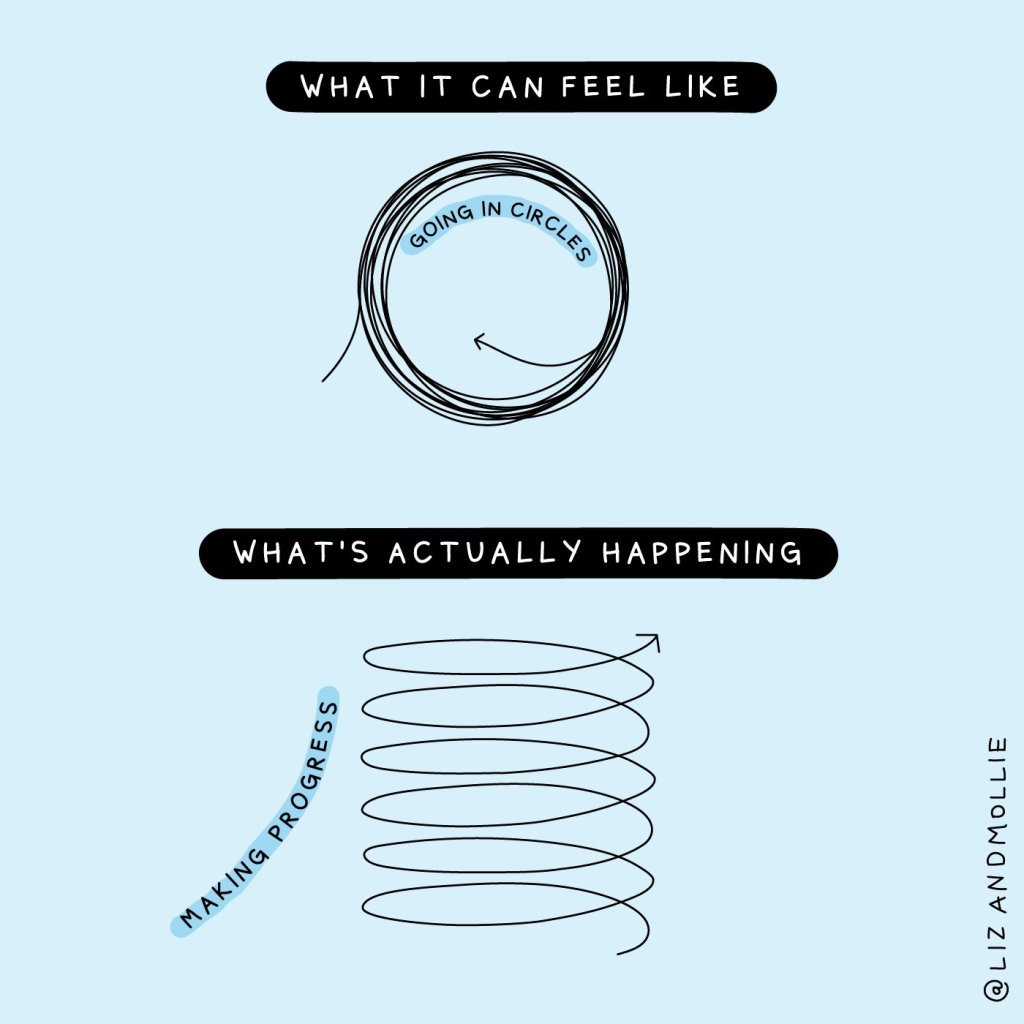

Once I’m in a place where I can undertake a true review, there’s always something I can learn. Be that based on feedback I’ve received, be that based on how I’ve handled either the initial experience or my response to it, or the onboarding of more knowledge linked to the strategic landscape which will enable me to do better next time. Being open to this learning is what moves failure iteratively towards success, and if we don’t find a way to engage with it, we’re just doomed to repeat the outcome.

Evaluate when a ‘no’ is a ‘not for us’ – taking yourself out of the mix

Context is key. Without it, you can’t truly get to a place where you can understand feedback. There is, for instance, a big difference between a no and a not for us. I mean, I know the outcome is the same, but the process of moving forward is different. If something is ‘not for us’ it feels different. A flat ‘no’ can feel like a value judgement. It can feel like the idea/work is bad. A ‘not for us’ doesn’t feel the same. It means that the drivers and vision of the people who are assessing don’t align with your proposal. There are always more people, though. There are always other visions, and so this type of rejection is actually an opportunity, an opportunity to find someone who better aligns with where you want to be. I find one crushes my dream, the other opens a different set of doors.

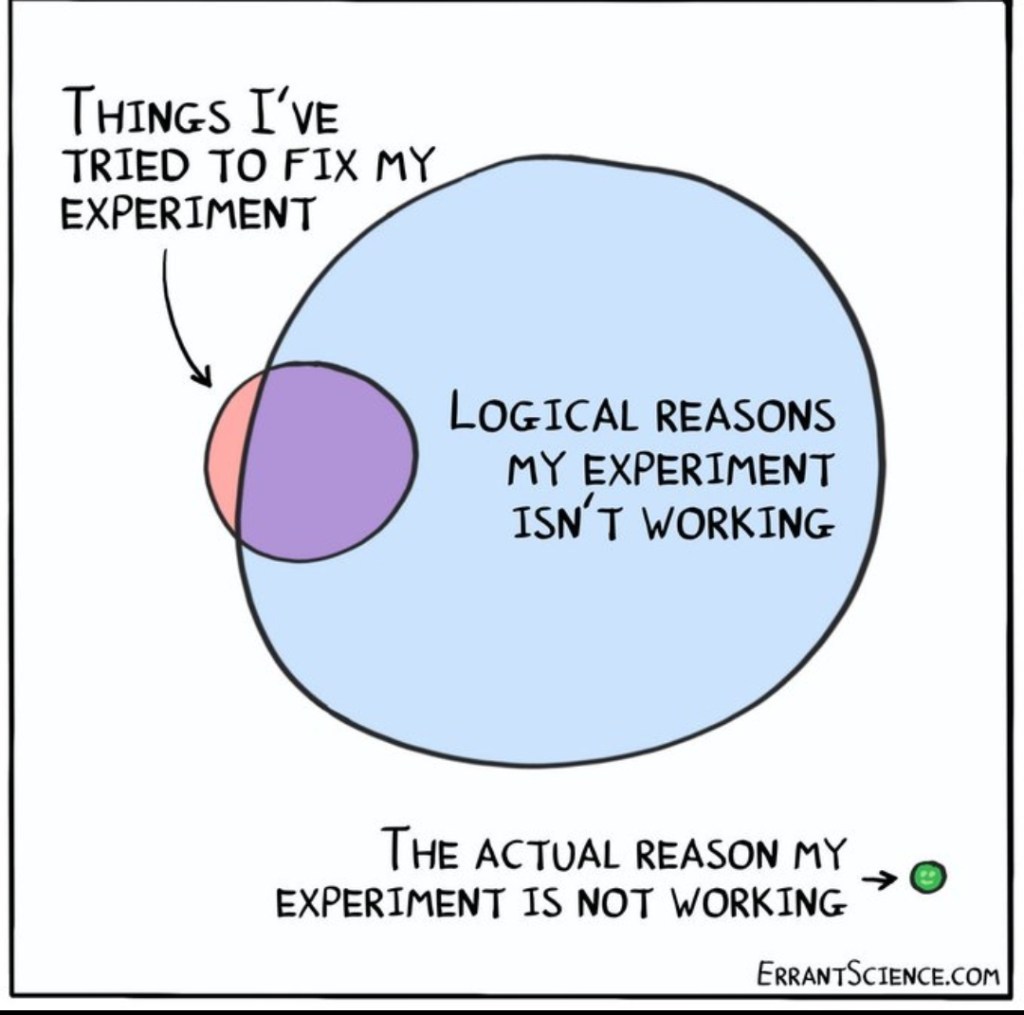

Focus on what you can control

So much of the scientific and writing process ends in a place where we are not fully in control of the outcomes. That said, in the process, there is so much that you can control. You can control your approach, who you are submitting to, what your aspirations for the work are, and how you balance that with other pieces of work that you have in process. I find I need to trick my brain so that when I have something that has reached the part of the process that I have little or no control over, I am still working on another piece of work where I am still in control of the process, be that a paper, grant, blog post etc. This helps to stop me spiralling and obsessing about something I can no longer influence.

Have a plan A, B, and C

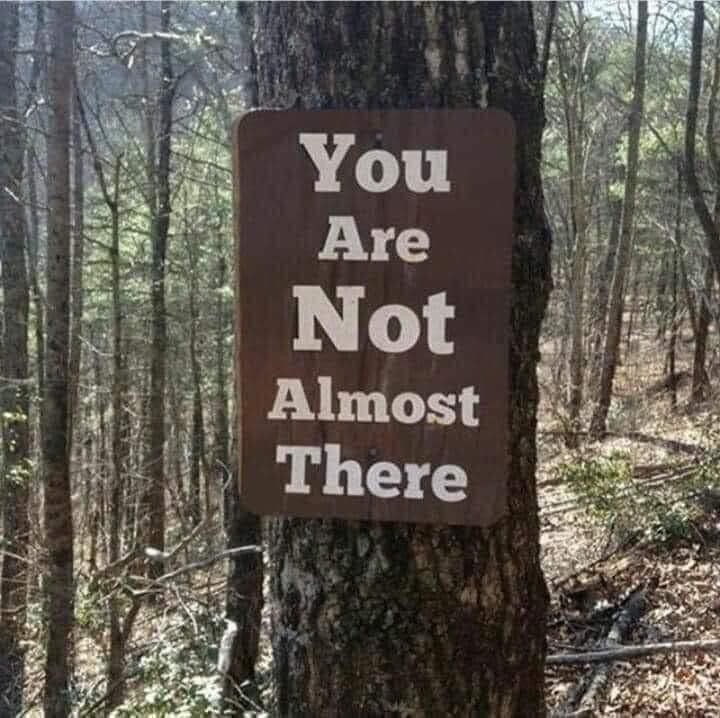

One of the key ways I’ve developed to maintain a sense of control is to understand there is never a single route to getting things done. There are always multiple ways to approach any aspiration and once you acknowledge this, you can make sure you include some of these alternatives in your planning.

The other component of this is to make sure that ‘the plan’ is rooted in realism, in both approach and time scale. There is nothing more disheartening than having a plan/approach that fails due to a lack of research/understanding. This is where your baseline skills as a researcher will come into their own. No matter the task, take the time to familiarise yourself with the barriers and options to ensure your plan is up to scratch.

Take inspiration from those who have succeeded

Big steps take time, and how you feel during this period is rarely static. There are times when I will love a paper, feel completely prepared for an exam, or feel like my dream could be a reality. Then, there are moments when I hate everything I’ve done and question why I thought I could ‘do it’.

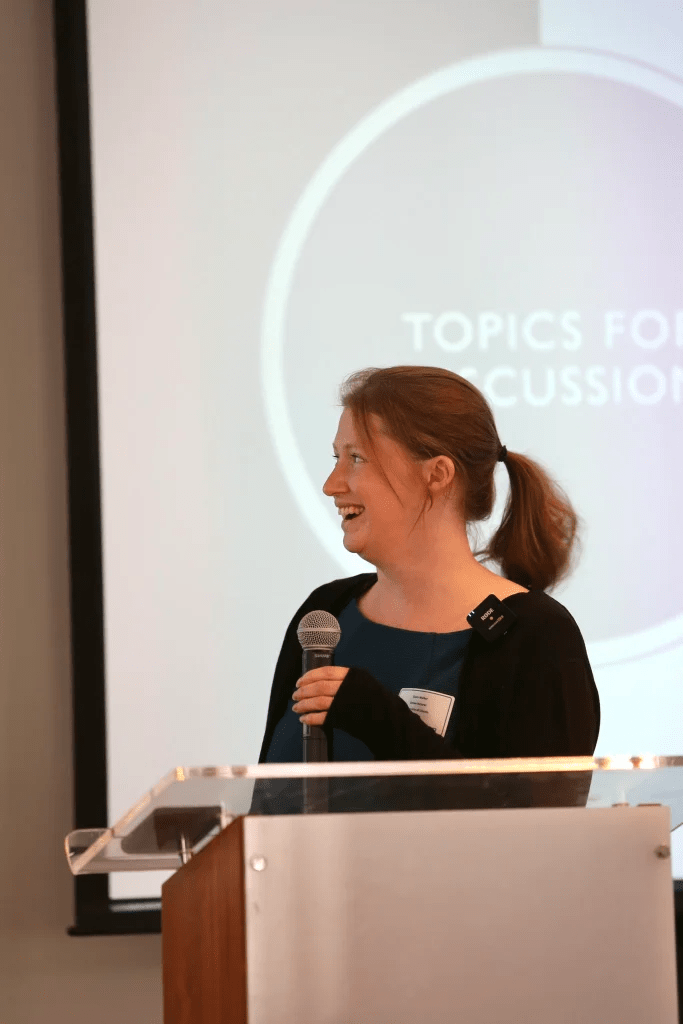

At times like these, it’s worth looking to others for inspiration. For instance, Professor Julia Lockheart and Professor Mark Blagrove from DreamsID (https://dreamsid.com/index.html) invited me to their book launch earlier this year. Seeing their dreams made real was really inspiring and provided an extra push to just get on with following my own. When everything feels too far from reality, look to those who can demonstrate the outcome you are aspiring for.

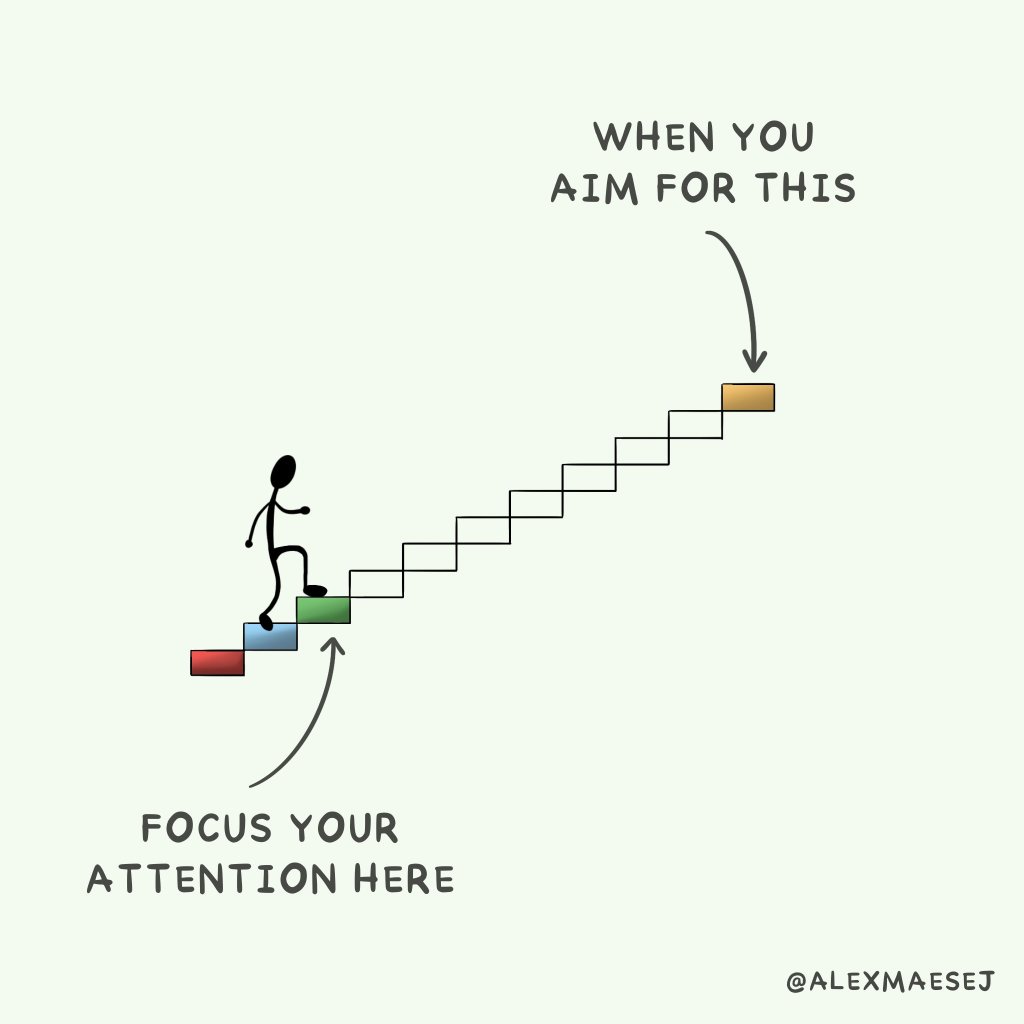

When it’s all too much focus on associated goals

Sometimes, the dream itself is not enough. Running head-on at goal can, at times, be both painful and exhausting. When this becomes overwhelming, it’s sometimes better to choose to come at things sideways or progress associated goals for a while. For instance, if that paper has been rejected for the 4th time, it might be time to write a blog post on it and use that as a different opportunity to think about the core message.

This can be a really useful approach for the lulls that will inevitably occur, either because you’re waiting on responses or because you have to build yourself up to try again. These periods can feel like ‘dead time’, and trying to make more direct progress can just leave you feeling despondent. Understanding this and knowing how you can keep going in a different way helps.

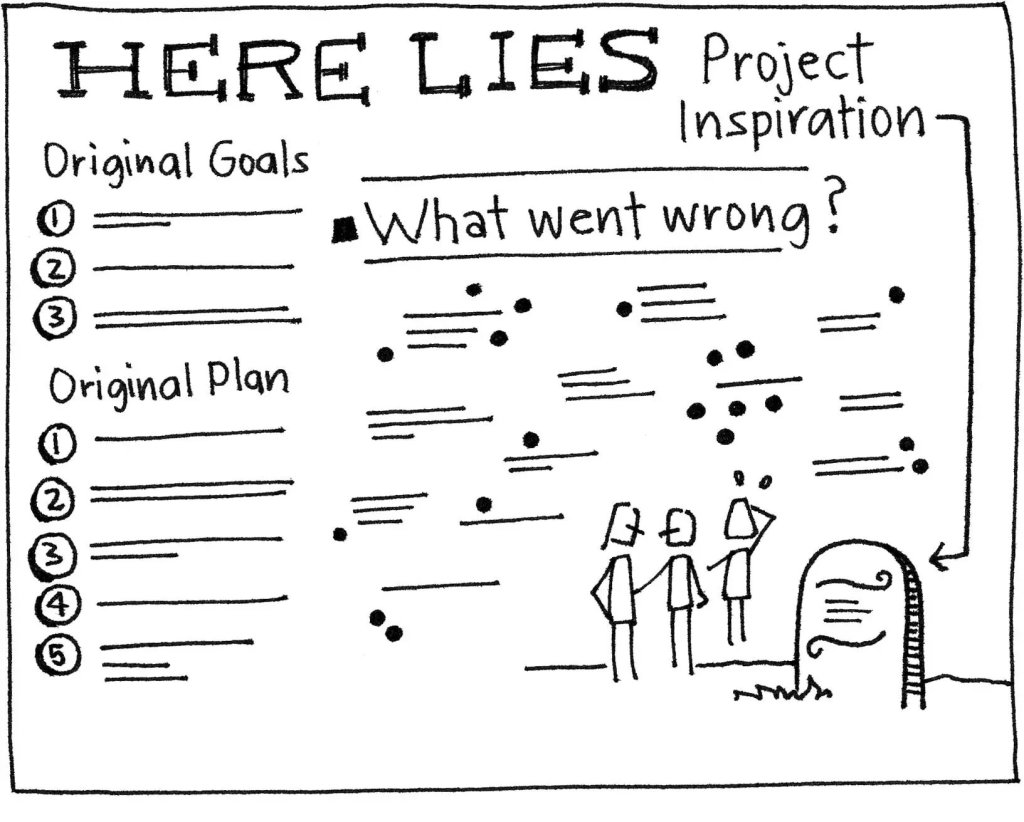

Press the reset button – Decide whether it’s worth the pain – Return to your why

Despite all of these thoughts about how to manage rejection and carry on, I want to make clear that it is also OK to think about quitting. This sounds a bit strange doesn’t it, after all, in science we don’t quit. Except we do. Part of our growth is being able to reexamine our work, be that an experiment, paper, or project in light of new information. When you get rejections, then it is important to decide whether someone has spotted a fundamental flaw that you just can’t fix or takes the work in a direction you just don’t want to follow. This isn’t encouragement to throw the baby out with the bath water, but an acknowledgement that there are times when the right decision is to pause or discard a piece of work and that it’s important to acknowledge that as part of our processing.

Evaluate progress made

Once you’ve decided that you are still invested or that the piece of work you are doing still has value, to you or others, then it’s important to remind yourself of how far you’ve come. It will always be further than you think. This is easier if you had a plan when starting out, but even if not, you can spend 10 minutes just listing all the steps you have proactively taken in moving towards your goal. Listing your rejections and the learning from them is a key part of this evaluation process. Putting everything down in one place may enable you to see opportunities you might have missed or help develop your plan B and C options further. I would advocate doing this regularly, even in the absence of rejections, but it can be a particularly useful re-centering process when things feel hard.

Understand that the only way is through

Finally, if you’ve decided that what you are undertaking still matches your why, and that it is not flawed enough to walk away from, the only thing to do is JFDI (just f**king do it). Keep the faith, both in the work and yourself, and go all in despite how hard it can feel. Have a plan and take a single step at a time, until, before you know it, you’ve reached your destination. Anything worthwhile is worth the effort, and future you will thank past you for your persistence and determination. Have a hard conversation with yourself, and just keep going.

All opinions in this blog are my own

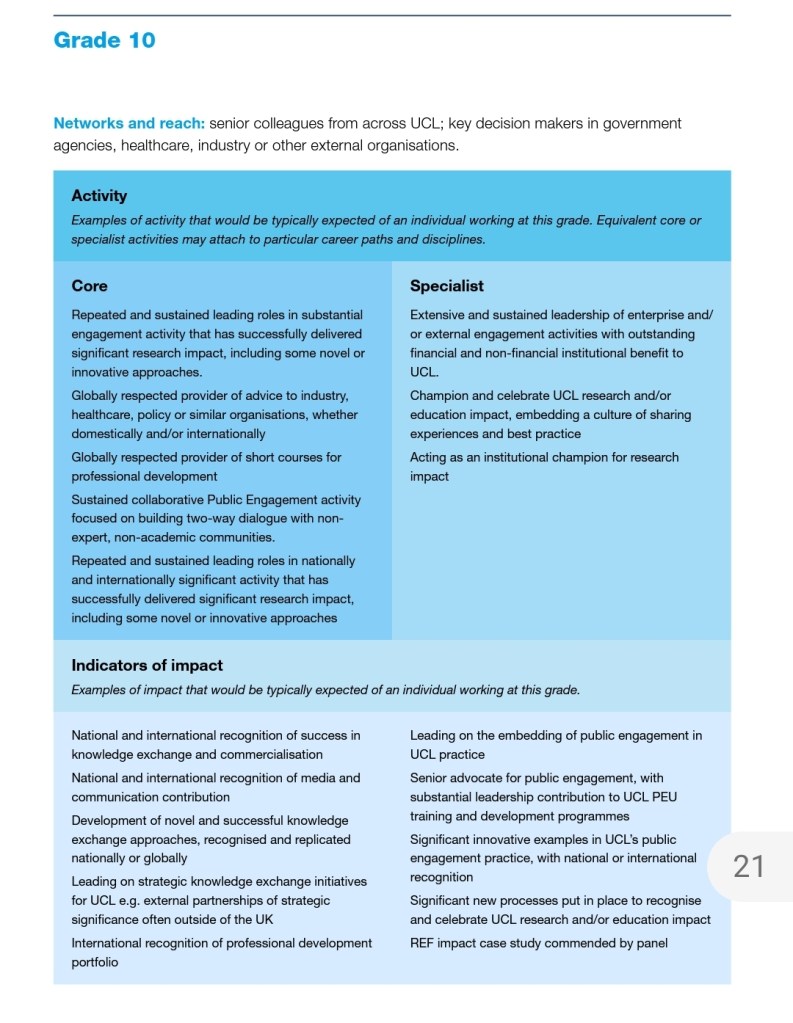

If you would like more tips and advice linked to your PhD journey then the first every Girlymicrobiologist book is here to help!

This book goes beyond the typical academic handbook, acknowledging the unique challenges and triumphs faced by PhD students and offering relatable, real-world advice to help you:

- Master the art of effective research and time management to stay organized and on track.

- Build a supportive network of peers, mentors, and supervisors to overcome challenges and foster collaboration.

- Maintain a healthy work-life balance by prioritizing self-care and avoiding burnout.

- Embrace the unexpected and view setbacks as opportunities for growth and innovation.

- Navigate the complexities of academia with confidence and build a strong professional network

This book starts at the very beginning, with why you might want to do a PhD, how you might decide what route to PhD is right for you, and what a successful application might look like.

It then takes you through your PhD journey, year by year, with tips about how to approach and succeed during significant moments, such as attending your first conference, or writing your first academic paper.

Finally, you will discover what other skills you need to develop during your PhD to give you the best route to success after your viva. All of this supported by links to activities on The Girlymicrobiologist blog, to help you with practical exercises in order to apply what you have learned.

Take a look on Amazon to find out more