Its 6am and I’m sitting listening to fire alarms go off in my hotel room at FIS/HIS. I’ve been up since just before 3 in a shame spiral of all the stupid things I said during day one of the conference and only just got back to sleep at gone 5am when the alarms started sounding. Frankly this feels like a metaphor for how my life has felt for the last 2 years, long and short the constant sound is exhausting and stressful. An hour later the alarms are still going and I’m now doing the only thing possible, which is to leave my room in some highly elegant nightwear and take myself, a laptop and a cup of tea to sit in reception to write. I may be looking a humiliating level of baggy eyed exhausted shell but at least it quieter and I have caffeine; which brings this metaphor all the way up to 2022. It’s better, I’m happier but oh lordy am I still broken. So as we sit in our 3rd year of dealing with the pandemic how are things different and how are they the same?

The things I love doing are so close to being back

One of the things that is currently saving my mental health and well being is that you can almost now envision the point where normality could return, or the new normal anyway. I know that if you have listened to politicians and social commentators recently you would think that normal is already here, but for me we’re not there yet. I can however do things like think about booking tickets for the future events (I cannot wait for Eurovision!) and hope they will go ahead, I’m contemplating planning trips and have started seeing friends in slightly less controlled ways. I’m even sitting here typing this at an in person conference, which has been surprising lovely and not stressed me out in the way I thought it would.

This being able to vision is important to me, it’s also important to me in the day job. For a long time all there was was SARS CoV2, you couldn’t plan, you couldn’t see a time when you would be able to do anything else. Now though things that give me so much joy in terms of education and research are coming back, papers are being drafted, grants are going in. I can see that we can begin to focus on other things with changes and improvements that need to happen. It may still feel like a shock but after all healthcare is NOT all about respiratory viruses and there are things beyond that which impact patient care that we need to take some time to focus on as well. All this said however, I have to re-state how tired I am and it is yet to be seen whether I have the inner resources to hit the ground running in the way that I would like.

Back on the carousel

Having just said how happy I am to be getting back to doing some of the ‘normal’ work of Infection Prevention and Control, there’s no getting away from the elephant in the room. We’re still dealing with a global pandemic, which a lot of the world seems to have forgotten. We’re still managing guidance changes, testing cases, investigating and managing hospital cases, but now with all of the funding support withdrawn and whilst being expected to also manage ‘business as usual’ on top of everything else. All that with having had 2 years of no sleep and no rest. In some ways, and this could be me, everything else is also more of a mess as we’ve been in crisis mode for so long. It’s not even as if the ‘business as usual’ is straight forward no even taking into account how much re-training needs to be undertaken.

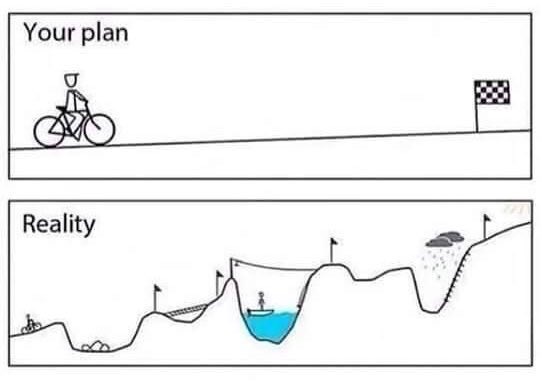

Because of all of this sometimes it’s hard to tell whether you are on a nice gentle carousel or are actually on the waltzers, trying to manage everything thrown at you in a landscape that is still constantly changing it’s priorities and demanding responsiveness to everything that is being put in front of you.

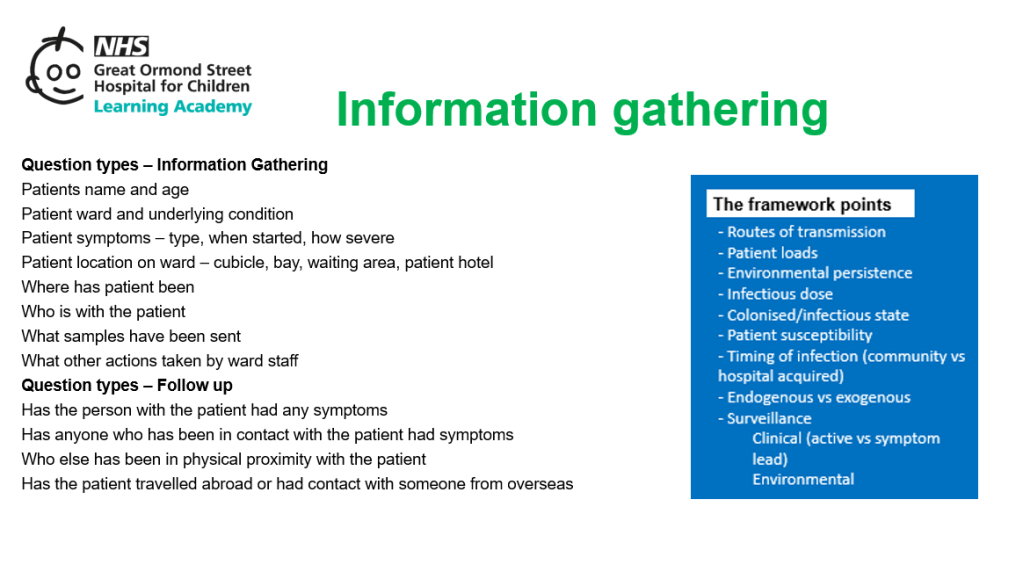

Single interventions don’t work

Everyone in the world still appears to be an expert in IPC and there still seems to be so much reductionism linked to the idea that a single change will revolutionise everything. I’m a little ‘over’ trying to have the discussion with people that covers the fact that almost all IPC is about introducing packages of measures/interventions. It’s what is often frustrating as a researcher, in that single interventions are therefore quite difficult to evaluate for their impact, but the world we live in clinically requires us to be able to control multiple risks and therefore manage multiple risk mitigation strategies simultaneously. The truth of the matter is that a single change will rarely control risk in the complex environments that our patients are in, even without adding the complexities of human behaviours and human interactions. I’ve written about this before, but I strongly believe we need to become comfortable with complexity and that part of our role in IPC is to assimilate complex multicomponent information, process it to make a balanced risk based set of decisions to establish a strategy, and then to implement that strategy in a way that appears simple and practical to those that are implementing. Taking the complex and processing it so that it can be disseminated in an accessible way is, I believe, one of the key talents of many IPC teams. We need to communicate this better as being one of our strengths and move away from single intervention focuses.

Could do with a little less ‘interesting’

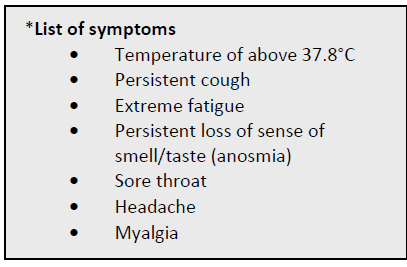

I don’t know about anyone else but i could do with less (take your pick) of monkeypox/lassa fever/polio/Burkholderia/invasive Group A Strep or any of the other ‘interesting’ alerts that we have had lately. I would normally love something novel to get my teeth into, but right now the ‘interesting’ seem to be coming thick and fast and I for one am only just managing getting back to MRSA and resistant Gram negatives. The constant ‘organism of the week’ just means that any return to balance feels like it’s going to be slow coming. I hate routine, it’s one of the reason I got into IPC, but even I could do with a little routine and boring for a while to find my centre and recover a little and recharge those batteries before embarking on the next new thing.

Summer down time isn’t so quiet

I think this has all been compounded by everything that has happened over spring/summer. Summer is usually the time in IPC where you can catch your breath a little, where you can plan for the inevitable challenges of winter and do the visioning piece to work out how you want to develop the service and move it forward so that everything works just a little better. This summer though there’s been little to no respite really, between new variants and waves earlier in the year and the new and ‘interesting’ since. Summer has been anything but quiet. This means that you know you are going to go into, what is predicted to be, a difficult winter without catching your breath and still trying to spin plates, with even more work having been pushed back to 2023. I think we will all still pull it off and I truly believe we will manage most of the things we were all hoping to achieve during the summer lull, I just fear that to make that happen we will carry ourselves into another winter running on empty. I think therefore we need to have the conversation with ourselves now about being kind, not just to other people but also to ourselves, and where you can plan accordingly.

Do more with less

All of this comes at a time when we are all very aware of the pressures on services and the resource limitation issues we are all facing. We can’t just do the same with less but we have to do more with less. The COVID-19 money has gone, the extra staffing support linked to it has gone, but a lot of that work hasn’t disappeared as we are all playing catch up on waiting lists and clinical work. It is easy therefore to feel pretty disheartened about the hill we need to climb, having already given up so much, both as individuals and as a collective.

The truth of this however is that some of the very pressures that sometimes feel like they are crushing us are also bringing some benefits. I am closer to my team than I’ve ever been. I’m more certain of the things that matter to both me and my service. I have significantly more clarity than I’ve ever had before both about my professional and personal life. Limitations on resource access have meant that we’ve had to worked harder to develop networks and build connections in order to use what we have better, and that connectivity has other benefits. So as much as I hate the words ‘better value’ I can see both sides of the coin, and not just about the money. I can see that it will make how we move forward better as we will move forward more together than we have ever been before.

The inevitable post mortem

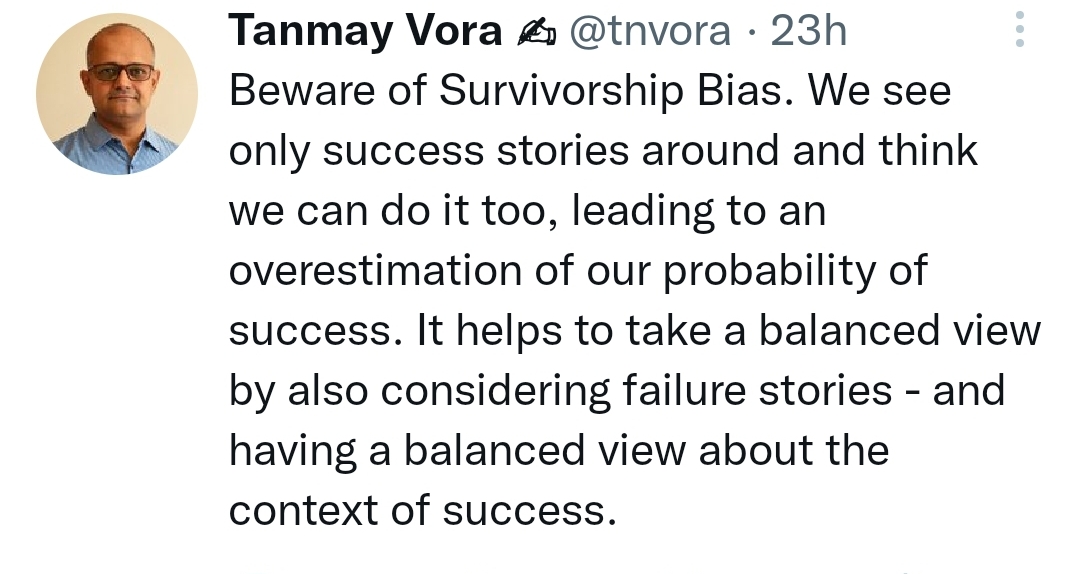

One of the things that struck me when I went through my first pandemic, swine flu in 2009, was the way that you could do nothing right for doing wrong. One minute you are heroes and the next you are villains because it’s politically expedient and someone has to be the focus of dissent. I know people that were upset by headlines during the Tory leadership contest that basically went after many of us who had stepped up on top of our standard roles to offer help and support. We stepped up because we felt it was the right thing to do and despite (in many cases) significant personal cost. Sadly, having been here before i was not surprised. Worse than that, I think we need to prepare for the fact that this will be the theme over the next 12 to 24 months, and that we will be used as a political football by many people. Hindsight is 20:20 and retrospective data analysis is a very different beast to prospective decision making. So my advice on this one is that we all need to develop a thick skin, understand what the drivers are for the headlines, and let it wash over you rather than taking it as the personal attack it can sometimes appear to be.

So having said all of this what do I think the next few months will hold? I think we will continue to be challenged, both in terms of the patients that present in front of us and in managing the service demands this places upon us. I do think that IPC teams and healthcare professionals will continue to step up and do what needs to be done to make care happen. As leaders however, we need to be aware of what that ask looks like and have strategies for managing it in an already tired work force. For me being able to focus on the future is how I get through the present, therefore planning for normal times is key to my survival. People ask how I’m putting in grants, drafting papers and planning change. I do it not because I have time and capacity, I do it because I have no other choice. I’m aware that it’s key to my survival, to keeping me grounded and enabling me to cope with the stress that exists in the now. Some people ostrich, I plan. As people are different however, I also know that my planning can stress others and so I try to be aware of how much I talk about the future to those people who are opposite and survive by living in the present. Dealing in the best way possible right now is mostly about knowing who you are. The clarity provided by the last two years of the pandemic has helped me in this by forcing me to know more about who I am and how best to manage myself. I have learnt and I hope to continue to use this learning to grow. So I will continue to hit the day dream button and drink tea……….I hope you find a way that works for you.

All opinions in this blog are my own