A decade ago, I posted this on my Facebook page:

The thing is, it will not have been the only bad science day I will have posted about. You see, science is wonderful, but some days, it can also be heartbreaking. Before the breakthroughs, there is often a period where it feels like nothing is ever going to work again. I currently have a few PhD students who are in the ‘I just need data phase’ and so I thought I would take this week to acknowledge how challenging it can be and share some things I learnt that got me through.

The results of your experiment do not define you as a scientist

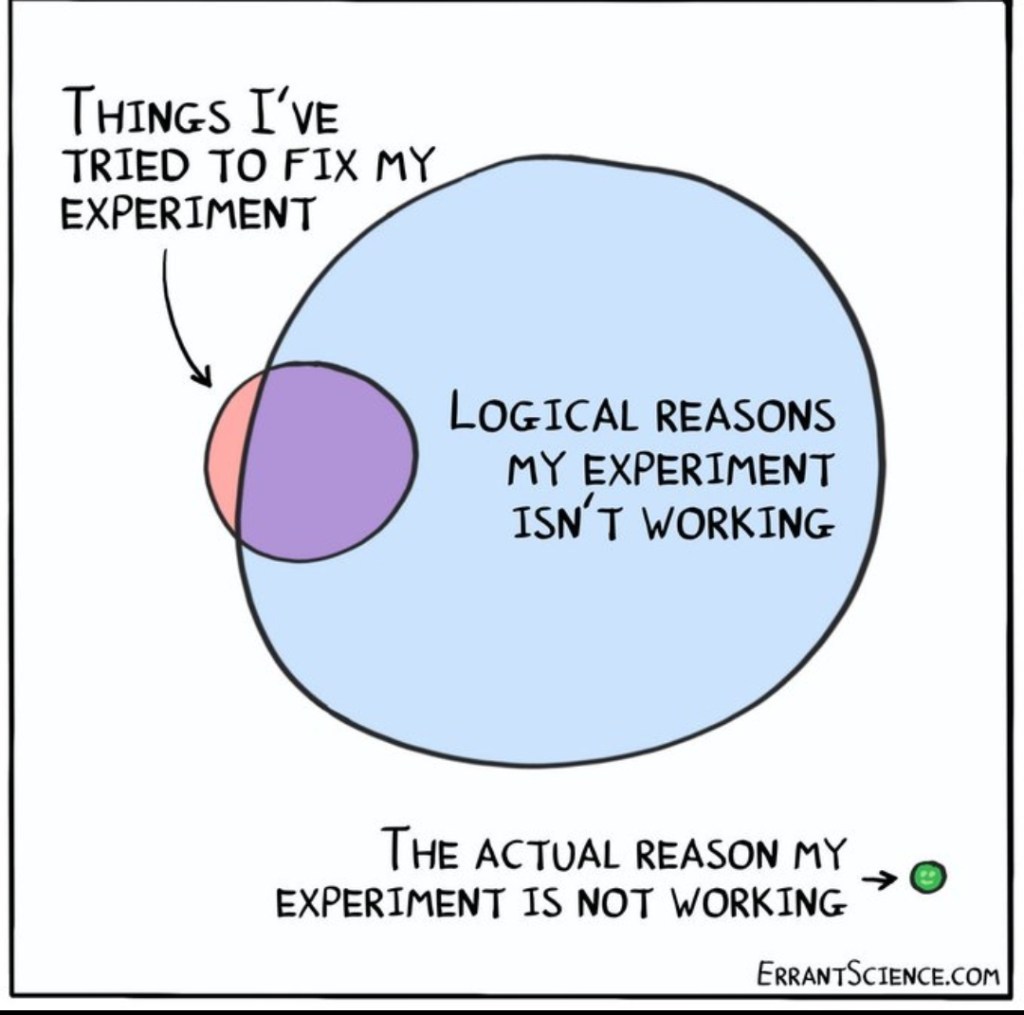

I want to say this first, and I want to say it loudly and on repeat, especially for all of those PhD and other scientists who are currently struggling with experiment failure – failed experiments DO NOT make you bad scientists! I shall say it again – failed experiments DO NOT make you bad scientists! All scientists fail, some of us have failed for months at a time, and challenging science is the name of the game. If you were doing something that had been done before, you wouldn’t be doing PhD level work. Therefore, failure, far from being a flaw, is to be expected. The sooner this is accepted, the better your mental health will be.

It’s incredibly challenging some days, but we all have to remember that our success at ticking actions off our list does not define who we are as people. Science is also far more than undertaking experiments. Did you sign up and deliver some kick ass outreach? Did you ask a great question in lab meeting? Did you make your struggling peer a cup of tea or help them with a figure they couldn’t get right? Sometimes, when the thing we’re obsessing about doesn’t go right, that is all we can see, and we ignore all the rest that is going well, make sure to acknowledge the good stuff.

Sometimes, you need periods of failure to get to the success

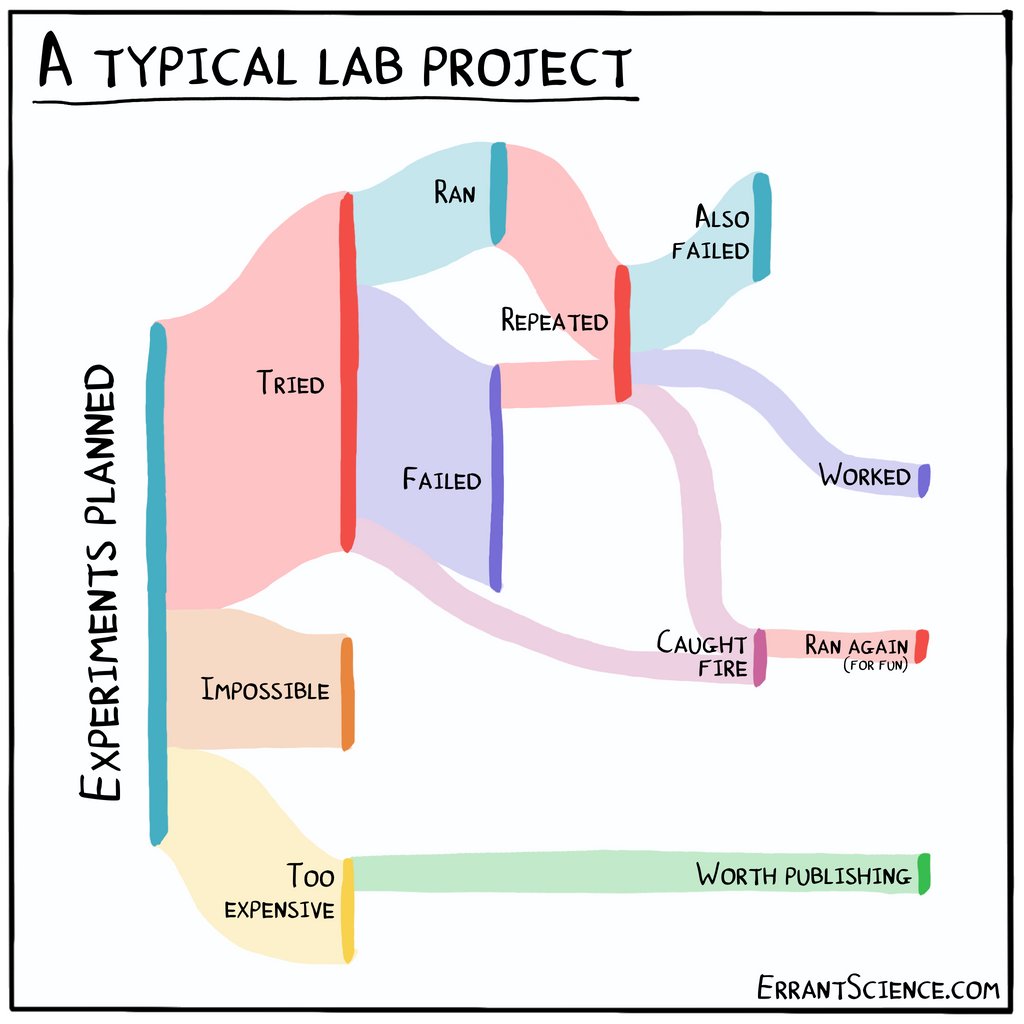

PhD’s are apprenticeships in research, and all of the failed experiments are far from a waste. They are part of the learning. You will use them to create your method development sections of your thesis, and they will give you great discussion points for your viva. In fact, if you had a completely clean sailing PhD that might be the more unexpected thing if I was your examiner, I’d be forced to dig more about where your learning happened.

Also, and I hate to do this as it’s the most trite thing ever, but some of the best science comes from mistakes and screw ups. Think Fleming and penicillin. The main thing is the mind set through which we view the failure. If we take it personally and let it get in our heads, all we can see is failure. Some of my best science has happened when failure has made me take a step back and pause, and suddenly I’ve seen the problem in a new light, or it’s forced me to make connections I wouldn’t have normally thought about. Sometimes, we need to be sure we see the failure as an opportunity rather than the end of hope.

It can be soul destroying when an experiment you’ve worked on for weeks or months crashes and burns, but the thing I’ve learnt is that often that happens when I push through too much, or don’t give it the attention it deserves. For me, experimental failures can also be warning signs about the pace and intensity of my work and can, in the end, offer a useful way to self check and force me to review my working patterns to give me a better more sustainable pathway to success. If you are crying over a failed run, it’s probably an indication that you need a break or to work differently.

Know when to continue down the rabbit hole and when to pivot

One of the biggest lessons I’ve learnt during my time working in science and doing research is that sometimes you have to be prepared to stop what you’re doing. During my PhD I spent 18 months trying to separate Adenovirus from viro cells using centrifugation to reduce whole genome sequencing read loading towards monkey rather than viral DNA. You know what, I got a bit of a reduction, but not enough to make a real difference, and to get that I worked till midnight for months as that was the only time the ultra centrifuge was available. What I didn’t do was a) set some success criteria b) stick to them and c) have a cut off that was based on effort vs reward. I just carried on…..and on……and on for very little payoff when I should have just stopped.

There will be times when you just need to persevere, as the work you are doing in central to the project and definitely achievable (anything core should be designed at the project level as attainable). There will, however, always be other aspects that need to be evaluated for the resource they are requiring (time, money, etc) vs what they are adding to your body of work. There is no point in spending 18 months on something that will be 2 pages in your thesis, there is point in spending 12 months fixing something that will be a chapter or more.

So one of the main skills I’ve had to develop is the ability to step back and see where the piece I am currently working on fits into the whole, and I can then evaluate what level of effort it is worth. If you haven’t set your success criteria etc beforehand it can be super painful to reach this decision and to walk away. This can be why having a good project timeline for your work/project/PhD can be really helpful. It helps you make pragmatic decisions and gets you out of the weeds in order to help you move forward with a view of the work as a whole.

Some days, you need to walk away to gain clarity

One of the things that has helped me with the ‘rabbit hole or pivot’ conundrum is getting to know myself enough to understand when I am in a spiral. My willpower and persistence are probably the only reasons I’ve managed to get as far as I have. The downside to these aspects of my personality is that I become hyper focused on a goal and the fact that it has to happen, I get in my own way and can’t always do the needed reflection piece. The end result of this is that it takes me longer than it should to realise I should have stopped (this is true of everything for me, not just experiments).

Believe when I say that it is worth developing the self-awareness to be better at this, as combined with the self reflection skill described above, it will be a powerful tool throughout your career. For me, this involved knowing when I need to walk away and distract my brain with some trashy TV or process it by writing a blog. My husband wishes it was the decision to go and load a dishwasher or clean, but no one can have everything. Pre-pandemic it was also things like going for a run, although I have to be honest and say I haven’t got back there. Whatever your technique, it took me a long time to realise this was a key part of my process. I needed to distract my brain, and the very process of doing this enabled me to gain clarity. Far from berating myself for my prevarication, it was actually key to achieving my aims and objectives.

Know when to get support

Frankly, sometimes you can’t manage alone. In fact, in my case, I hardly ever can. It’s why I really believe that science is a team sport. Sometimes, you will need someone else to help you recognise that it’s time to evaluate. Sometimes, you will need the support of others as part of the reflection process, and when it comes to troubleshooting why things are not working, two heads are definitely better than one. Far from being a sign of weakness, seeking support and building networks so you have identified that support are key parts of your career development. There will always be people out there who have more experience than us and learning from them so we don’t just replicate each others mistakes is just good resource management.

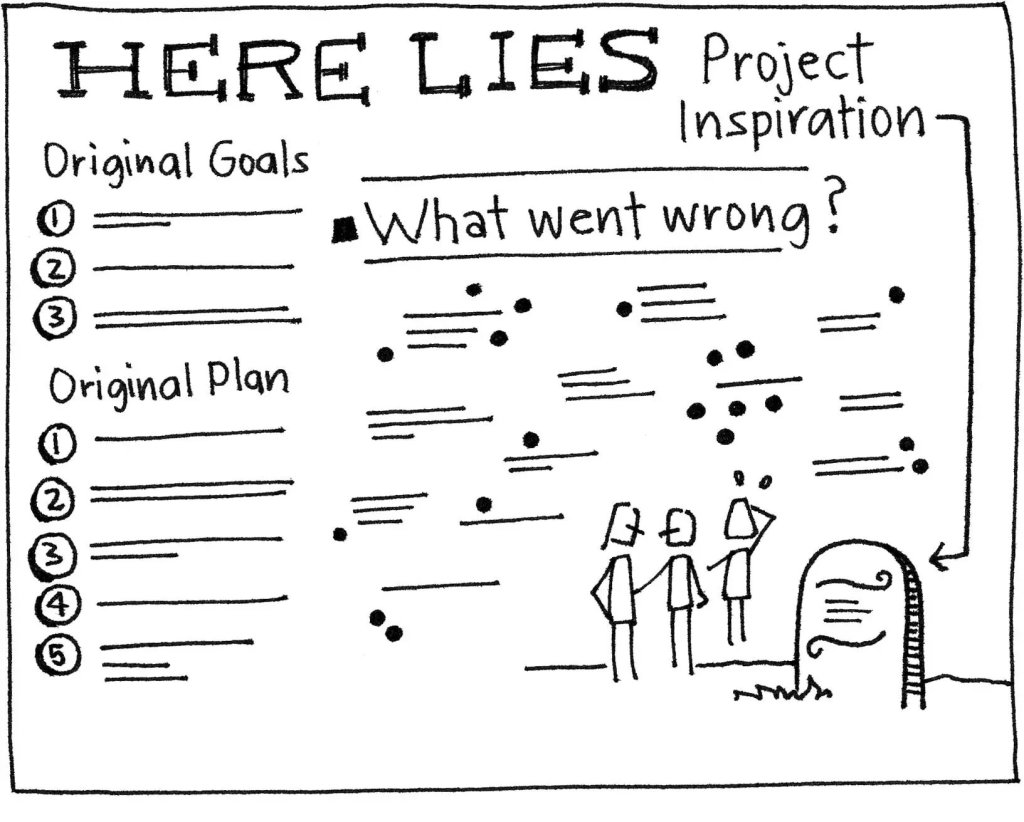

Always have a plan b, and ideally c and d

As I’ve already said, failure is just part and parcel of science. There’s no escaping this fact. What I have learnt though is there are routes to being more savvy about anticipating that failure. I had a fairly horrid experience during one of my masters degrees, where the project was designed as just one thing that either worked or it didn’t. Inevitably it didn’t, and I was forced to write 10,000 words on 3 results. This taught me 2 valuable lessons, 1) never blindly follow a project designed by someone else, if you feel it isn’t right for you own the fact that it is your project and you need to input to get it where it needs to be, and 2) never design a project that is entirely dependent on plan A working, as the chances are it won’t.

Taking a modular approach to any project design will enable you to combine parts that work and still have an over arching narrative that makes sense and enable you to succeed, even if individual components fail. If you are designing a project around a core component that you are then attaching spokes to, that component needs to be guaranteed in terms of process success, even if not result outcomes, as you can discuss the results in the context of your work, but you can’t risk not being able to get them. Take time to map this out and to undertake a SWOT analysis, so you can pre-plan for how you will manage any failures. That way you won’t lose time panicking when things go wrong, as you will have a defined pathway already.

Don’t benchmark against the success of others

A lot of the way in which we experience failure is defined by how we emotionally respond to the context of that failure. Sometimes benchmarking against others can be helpful, but more often than not if you are already feeling challenged it can just add to the pressure you are already feeling. I think this especially true when taking a PhD, as both you and your project are highly individual. It can be to look at others and their outputs and not compare, but the truth of the matter is you are likely comparing apples and oranges. PhD’s by their very nature need to be unique pieces of work, and so someone can appear to be killing it but their track record will look different to yours as they might face their challenges in the future, or may have to justify their work in a different way. So look to peers for support rather than affirmation of your progress, as every pathway in different. Otherwise you can make a challenging time even worse for yourself.

Know that we have all been there

I started out by saying that failed experiments do not make you a bad scientist and I want to finish by saying that the way I know this to be the case is that I have yet to meet any scientist who hasn’t spent dark days dealing with failed experiments, or just failure in general. No matter how lonely it feels in the moment, know that we have all been there. That may not make it feel any better, but I hope it empowers you to reach out and let your supervisors/peers know how you are feeling in order for them to support you through it. No one should judge you in this, because in judging you we would be judging ourselves. Science can be a really lonely profession, but it doesn’t have to be, and so reach out to your networks, and if you can’t reach out to them reach out to me. The better job we do of supporting each other the better placed we will be to create work that matters and improves the world just a little bit.

All opinions in this blog are my own

If you would like more tips and advice linked to your PhD journey then the first every Girlymicrobiologist book is here to help!

This book goes beyond the typical academic handbook, acknowledging the unique challenges and triumphs faced by PhD students and offering relatable, real-world advice to help you:

- Master the art of effective research and time management to stay organized and on track.

- Build a supportive network of peers, mentors, and supervisors to overcome challenges and foster collaboration.

- Maintain a healthy work-life balance by prioritizing self-care and avoiding burnout.

- Embrace the unexpected and view setbacks as opportunities for growth and innovation.

- Navigate the complexities of academia with confidence and build a strong professional network

This book starts at the very beginning, with why you might want to do a PhD, how you might decide what route to PhD is right for you, and what a successful application might look like.

It then takes you through your PhD journey, year by year, with tips about how to approach and succeed during significant moments, such as attending your first conference, or writing your first academic paper.

Finally, you will discover what other skills you need to develop during your PhD to give you the best route to success after your viva. All of this supported by links to activities on The Girlymicrobiologist blog, to help you with practical exercises in order to apply what you have learned.

Take a look on Amazon to find out more

[…] Top Tips: Finding the inspiration to develop your research question PhD Top Tips: How to carry on when the experiment you’re doing just feels cursed My Best Science Comes from a Cup of Tea: My top tip for Healthcare Science Week The Second […]

LikeLike