I am currently in the middle of secret project, which I hope to announce more about in late August/early September. I’m really excited about it but it’s taking a bunch of my time. I’m hoping that you will be just as excited when I can share more details. The wonderful Dr Claire Walker is helping me deliver my passion project by curating the Girlymicrobiologist blog for a few weeks. This means that I hope you all enjoy getting some great guest blogs from a range of topics. Girlymicrobiologist is a community, and all of the wonderful authors stepping up, sharing their thoughts and projects, to support me in mine means the world. I hope you enjoy this guest blog series. Drop me a line if you too would be interested in joining this community by writing a guest blog.

Dr Walker who is a paid up member of the Dream Team since 2013, token immunologist and occasional defector from the Immunology Mafia. Registered Clinical Scientist in Immunology with a background in genetics (PhD), microbiology and immunology (MSc), biological sciences (mBiolSci), education (PgCert) and indecisiveness (everything else). Now a Senior Lecturer in Immunology at University of Lincoln. She has previously written many great guest blogs for the Girlymicrobiologist, including Microbial Culture: An Immunologist’s Side Project Gone Wild.

This weeks blog post continues this months fungal theme (all things yeast) and is from the absolutely amazing Kate Rennie. Kate is a born microbiologist, even if she was diverted by the world of nursing and has gone on to become a cracking Infection Prevention and Control nurse. Her curiosity and willingness to learn and expand her skill sets, makes it no surprise to me that when she decided to expand her hobbies, she decided to go down a route that touches on all things micro.

Before we get into the sour dough however, let’s start by talking what coeliac disease (the condition that leads to the requirement for gluten free bread) as written for us by Dr Claire Walker, our in-house immunologist:

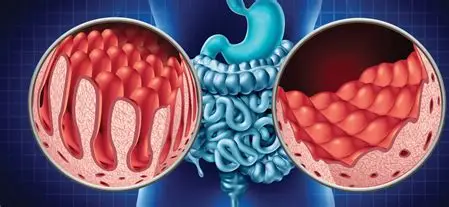

Coeliac disease is a serious autoimmune condition where eating gluten, a protein in wheat, barley, and rye, triggers the immune system to attack an enzyme in the gut called tissue transglutaminase. This damages the villi, tiny structures in the small intestine that absorb nutrients. The result? Symptoms like bloating, diarrhoea, fatigue, and iron deficiency. But it doesn’t stop at the gut. Some people develop dermatitis herpetiformis, an intensely itchy, blistering skin rash. Others experience neurological symptoms such as brain fog, headaches, and numbness or tingling in the limbs. It’s often misdiagnosed or missed entirely.

Around 1 in 100 people in the UK have coeliac disease, but most remain undiagnosed. Diagnosis usually starts with blood tests (like the tTG-IgA), followed by a small bowel biopsy to confirm intestinal damage. These tests only work if you’re currently eating gluten. So if someone’s already gone gluten-free and are feeling better, they need to reintroduce it for several weeks which can cause symptoms to reappear and puts many people off testing.

There’s no cure and the only treatment is a strict, lifelong gluten-free diet. That means no “cheat days” as even tiny amounts can cause damage. It takes serious commitment: careful label reading, avoiding cross-contamination, and asking awkward questions when eating out. But for most, removing gluten thankfully leads to major improvements in symptoms and overall wellbeing.

Blog by Kate Rennie

What am I growing in my kitchen… a gluten free sourdough journey through the eyes of an IPC nurse

I’m Kate, I’m an infection control nurse at GOSH. I’ve worked in infection control since 2020 (1.5 years in primary care, 9 months in community/mental health and I’ve been at GOSH since April 2022). I was diagnosed with Coeliac disease in 2013 and decided 2025 would be the year of new hobbies and I am bored of gluten free bread that resembles cardboard.

I decided to embark on my sourdough journey (albeit slightly late to the party as I know this was a lockdown thing). I didn’t actually know what I was getting into with making sourdough, I read the first few steps and thought it sounded pretty simple, flour and water in a jar.

My flour and water sat on my kitchen side in a jar for 2 weeks (gross), and I named it Marilyn (Mondough)… I nurtured her and fed her daily, for those who may remember Tamagotchi’s, this is how I can describe it and as a previous Tamagotchi owner, I loved it.

Part of me was obsessed with what have created and look forward to waking up each morning to see how it’s looking (highlight of your late 20s) but the infection control nurse in me is slightly grossed out by it. I’ve read a bit more and learnt a lot, she just needed a little bit of extra love and care (troubleshooting) at a few days old.

HOOCH – I’ve only ever known hooch as this from my late teens/early 20s.

Fast forward to my late 20s, this is a sign that your sourdough starter is hungry, it’s eaten all its nutrients, and you must feed it more frequently. I was reluctant to throw her away and start fresh so I added teff flour in the hope she would perk up and SHE DID.

But she smelt disgusting… A familiar reminder of my 16 year old, pre-nurse self, having my long acrylic nails removed in the salon. ACETONE?? Apparently, it’s a byproduct of fermentation…

So, I wondered if this was actually safe to have something fermenting in my kitchen with absolutely 0 knowledge and thinking I’m probably going to poison myself. After a bit of research, I learnt this is normal and how to fix it, yet again, she’s hungry and I’m a rubbish mother.

Whatever is happening inside that jar is creating its own yeast to make it grow which is quite cool! I’m not sure how many people have actually gone this deep into the thought of a sourdough starter, but my IPC brain is fascinated yet disgusted and I want to know more. Do I want to culture it in the lab? Probably not. Am I going to eat it? Most definitely.

Fast forward 2 weeks… My sourdough journey ended abruptly after my first loaf. I felt disheartened that it didn’t turn out like the GF loaves I’d spent too much time obsessing over on Tik Tok.

The perfectionist I am wanted the perfect loaf to happen first time, so I abandoned sourdough and ventured into making non-sourdough gluten free bread. I popped Marilyn in the fridge for when I decided to revisit sourdough making and there she stayed for a good 3 months. Apparently, this puts it to sleep, and you can later revive it… but after pulling it out the fridge and seeing a layer of black liquid on top of the starter, my IPC brain got the better of me and I decided with my limited knowledge of sourdough and fermentation at home, it probably was best that I didn’t consume this and decided to throw it in the bin and I spared a brief thought for what Marilyn was and could have been if I had more patience.

I’d hoped this would be a success story about my gluten free sourdough rather than a failure but basically, sourdough isn’t easy and gluten free sourdough, really isn’t easy. It truly is a science.

Gluten free bread making in general is a delicate science because it lacks the key protein—gluten—that gives traditional bread its structure, elasticity, and chew. In wheat-based breads, gluten forms a stretchy network that traps gas bubbles from yeast, allowing the dough to rise and hold its shape. Without gluten, you have to rely on a blend of alternative flours—like rice, sorghum, or buckwheat—each contributing unique properties such as starch, protein, or flavour. Binding agents like psyllium husk are also essential to mimic gluten’s elasticity. No single gluten-free flour can replicate all the functions of wheat flour, which is why crafting a successful gluten-free loaf requires a carefully balanced mix rather than just throwing in a single substitute flour and hoping for the best.

I have been successful on a few occasions in making non-sourdough gluten free bread which has still been a real insight into science in everyday life.

To all life’s problems there are solutions if only we are curious and passionate enough to see them and change direction in order to maximise our successes. It appears Kates’ experience with sour dough as part of her coeliac journey is no different.

All opinions in this blog are my own