I am so excited by todays’ guest blog post. I’ve been so eagerly awaiting sharing it with you all. I don’t have any tattoos myself but it is something that is common amongst my friendship group, and I get asked about tattoo related infections A LOT. Partly as I was involved in some of the investigations when there was an issue some time back. So, a post that could help address some of the risk assessment and best practices linked to this art form felt very necessary, even though I didn’t feel I was best placed to write one. Then I saw this great article from Julie Russell on LinkedIn and I just had to reach out and see if she fancies writing a guest blog for me, and thankfully she said yes!

I first met Julie as Head of Culture Collection at Public Health England, that has since changed it’s name to the UK Health Security Agency. She was an inspiring microbiologist, who just had so much knowledge, and she became a great phone a friend. Since then she has moved on to work in a really different area where she still gets to put her microbiology and infection prevention and control knowledge to good use, as the director of a tattoo/art studio in Muswell Hill. No one is better placed therefore to answer the questions that I always get asked and have not felt best placed to answer.

Blog post from Julie Russell

After years in NHS microbiology laboratories, I joined the Public Health Laboratory Service, where I provided external quality assessment schemes and reference materials to laboratories worldwide. After that, I decided to do something completely different. I now co-own and manage Old Marine Arts Group, a tattoo studio in Muswell Hill, London.

It hadn’t occurred to me that tattooing, one of the oldest art forms in the world, essentially creates controlled wounds on people to decorate their bodies. I’ve had tattoos since my 20s – my first done in a legalised squat by a friend who’d never tattooed anyone in his life before. There was no personal protective equipment (PPE) involved; it healed beautifully, and I didn’t think about it anymore.

Many thousands of people across the UK have similar stories with no ill effects. Yet infections linked to tattooing have been recognised since the 19th century, and the government quite reasonably seeks to minimise such risks.

Tattooing, Skin, and Infection Risk

Bear in mind that the skin has a rich, diverse microbiome consisting of millions of microorganisms, some of which can cause infections if the skin is broken. Tattooing involves puncturing the skin with needles thousands of times, to a depth of approximately 1.5-2 mm, to place pigment into the dermis, creating a permanent design. Invariably, the tattoo process causes some bleeding, and after it’s finished, short-term redness, swelling and scabbing are normal. Resisting the urge to scratch is essential to minimise the risk of infection.

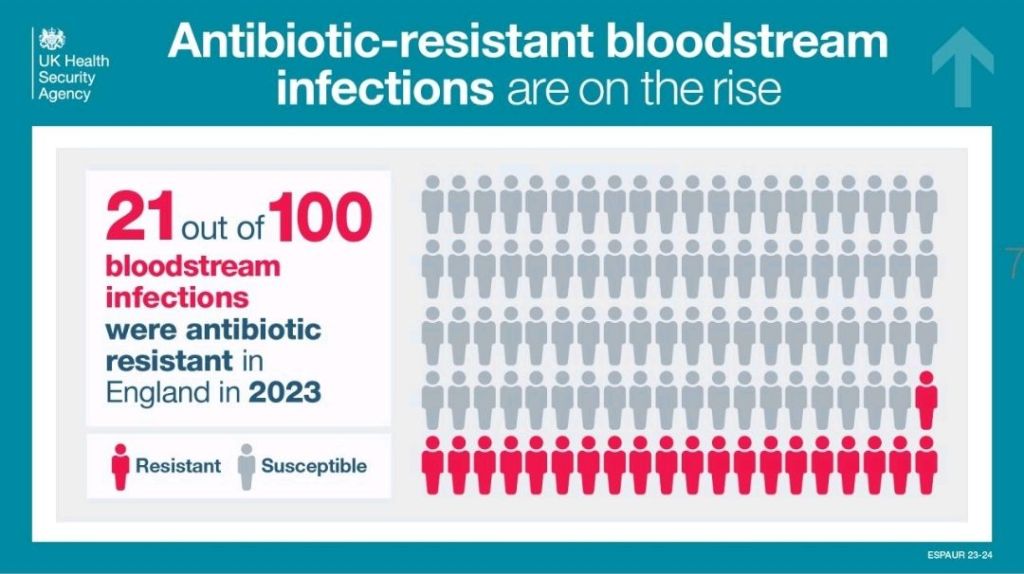

A July 2024 YouGov1 poll suggests 28% of UK adults – around 15 million people – now have tattoos. The UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) notes that the true prevalence of tattoo-associated infections is unknown. There are no statutory notification procedures in place for infections specifically caused by tattooing, and no indication that such infections significantly burden the NHS. Various estimates suggest that approximately 1-3% of tattoos become infected in the UK. Most infections are mild local skin infections that can be treated with a single course of antibiotics; severe infections remain rare.

Interpreting the Evidence

Publications on tattoo-related infections must be read with caution. A December 2024 paper in The Lancet Microbe2, “Microbiology of tattoo-associated infections since 1820”, highlights rare severe cases such as necrotising fasciitis, leprosy and atypical mycobacteria outbreaks. The authors state that, “Despite advancements in public health policies and increased awareness of tattoo-related risks, a notable rise in both the number and diversity of microbial infections has been observed with an increase in the population opting for tattoos, particularly since 2000”. However, they provide no population-level denominators and conflate expected irritation, redness and swelling with true microbial infections. The authors fail to note that severe cases are overrepresented in the literature precisely because they are unusual. The paper may be a useful clinical catalogue, but it is not an incidence study.

A Brief History of Safety

Tattooists and clinicians have long recognised infection risks in tattooing. In the late 1800s, some artists infamously spat into powdered ink and sucked the needles during the tattooing process. Meanwhile, London-based artists in the early 1900s, such as Alfred South, promoted “the most perfect antiseptic treatment, painless and absolutely harmless”, whilst Tom Riley warned: “Caution to Ladies and Gentlemen thinking of being tattooed – First see the work of two or three tattooists then make choice {sic}. See that a complete set of new needles are {sic} used at each sitting as well as antiseptics”. Some early tattooists even wore white coats to convey a clinical level of cleanliness.

Legal regulation, however, arrived much later. It was still legal to tattoo children in the UK until the Tattooing of Minors Act 1969. Some aristocratic families reportedly tattooed babies for identification – in case, for example, their children were hospitalised or kidnapped.

Modern Regulation

Mandatory licensing changed the landscape. Under the Local Government (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1982, tattoo studios need to be registered. More recently, there is the British Standard BS EN 17169:2020, which covers safe and hygienic practice, although not many councils use it as a benchmark. This standard covers workplace preparation, equipment sterilisation, PPE, client consultation and aftercare. It requires studio owners to implement a comprehensive hygiene protocol to protect clients and staff, and tattoo artists to provide evidence of continued professional development.

Wales now requires tattooists to complete and pass a regulated Level 2 Infection Prevention and Control Award. Requirements in England and Scotland are less specific. Barnet Council licenses my studio; their Code of Practice 13 details the specific requirements for tattooing activities, in addition to those laid down in the Regulations applicable to all special treatment licensed premises. It notes that tattoo artists who are unable to demonstrate hygiene competence may be asked to complete a Level 2 hygiene certificate.

Reducing the Risk

Infection risk can be reduced through:

- Good personal hygiene (artist and client)

- Effective cleaning

- Separating clean and dirty materials

- Correct sterilisation or disposable equipment

Artists must assess clients for skin issues (including rashes, moles and scarring), alcohol or drug use, and relevant health risks (e.g. allergies, immunosuppression, pregnancy). Artists must be vaccinated against Hepatitis B.

Tattoo stations should be treated as clinical areas. Equipment must be protected from contamination; inks must be decanted into disposable cups; distilled water used for dilution of ink and ‘green soap’ (a vegetable-oil-based surgical soap used in the tattoo industry) or for washing the needles between colours.

Dressings applied afterwards are usually transparent, self-adhesive, polyurethane film (known as second skin in the industry), similar to those used for burns and post-operative incisions, or cling film attached to the skin with surgical tape. Clear aftercare guidance should be provided verbally and in writing about how to care for the tattoo whilst it heals (no swimming, spa pools, sunbathing, perfumed soaps or scratching).

Unlicensed Tattooing

Although it is illegal to tattoo in unlicensed premises, this is rarely enforced. Anyone can buy machines and inks online and tattoo friends at home, often with limited knowledge of hygiene.

Inspections across the UK vary, with some councils inspecting only once when the studio opens, while others do so more regularly. Licensing rules differ widely outside the UK. Excellent tattoo studios can be found abroad, but so too can be deplorable hygiene. Getting a tattoo may be a more permanent souvenir of a fun holiday than a fridge magnet, but it can be risky, and alcohol and sunshine don’t help healing.

Final Thoughts

Tattooing in the UK, when performed by licensed professionals, carries a low risk of infection. I believe the demand for tattoos will grow, and I support nationally enforceable, pragmatic safety standards.

Takeaway messages:

- Tattooing by licensed professionals in the UK is low risk

- Nationally recognised training and regulation are likely to emerge

- A tattoo is a controlled wound—so please, as I once observed, don’t let your dog lick it

References

- YouGov 16 July 2024: When it comes to tattoos, which best applies to you? | Daily Question

- Kondakala, Sandeep et al. Microbiology of tattoo-associated infections since 1820 The Lancet Microbe, Volume 6, Issue 4, 101005

Training For Aspiring Tattoo Artists:

After two years in the tattoo industry, I now work with licensed tattoo artist, TomCatTatt, to provide introductory training for aspiring tattoo artists, covering the basics in safety and hygiene, legislation and licensing, and an introduction to tattooing techniques. Contact me for more information: julieru13@hotmail.com.

All opinions in this blog are my own