Norovirus is estimated to cause more than 21 million cases every year worldwide and to cost the NHS over £100 million every year. Because of its impacts, there’s been a fair amount in the news related to Norovirus recently as the numbers have been up this year. I thought the timing might be good, therefore, to talk about this clever and tricky virus, and why we should care about it even if it is not likely to result in significant harm to most people.

In their recent blog post the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) have listed a number of reasons why levels might be higher at the end of 2024 than in recent years:

- Post-pandemic changes in population immunity

- Changes in diagnostic testing capabilities

- Changes in reporting to national surveillance

- A true rise in norovirus transmission due to the emergence of GII.17

I’ve written a post before about food poisoning and food borne outbreaks, but as Noro (Norovirus) is the queen of this particular court, I thought it was high time I gave her the recognition she deserves and explain some of the reasons they’ve listed in more detail so that the reasons might become clearer.

What is Norovirus?

So, let’s start by talking some virology. Feel free to skip this section if the technical stuff doesn’t really appeal to you, I’ll try to include plenty of context in the other sections so they still make sense.

Norovirus is a single-stranded positive sense non-enveloped RNA virus, but what is that, and what does it mean?

- RNA (ribonucleic acid) – We talk about DNA being the building blocks of life but viruses act a little different as they are able to take over the mechanics of the cell/host they invade. This means they dont have to have DNA to function. Their genomes (the code for what they are) can be made from RNA alone.

- RNA molecules range widely in length and are often less stable than DNA. RNA carries information that can then be used to help cells build proteins using the machinery in the host, which are essential for replication and other steps

- Single stranded – RNA is frequently single stranded, versus DNA, which is normally double stranded (there are however examples of single stranded DNA viruses, such as Parvovirus)

- Positive sense – Noroviruses use their own genome as messenger RNA (mRNA). This means the virus can be directly translated (tell the cell what to do) into viral proteins by the host cell’s ribosomes (cell machinery) without an intermediate step

- Non-enveloped – This refers to a virus that lacks the lipid bilayer that surrounds enveloped viruses, meaning that they are sometimes called ‘naked’. These viruses are more resistant to heat, dryness, extreme pH, harsh treatment conditions, detergents, and simple disinfectants than enveloped viruses.

Noro is part of the family Caliciviridae, and human Norovirus used to be commonly referred to as Norwalk virus. As genetic information has become more available, it is now known that there are 7 common genogroups or G types of norovirus (GI – GVII), only some of which can infect humans (GI, GII and GIV).

Within these main genogroups, GI and GII contain a number of different genotypes, which will circulate at different amounts across different years and cause most of the infection we see in the population. You can also probably see that, although we use numbers to talk circulating strains, they also commonly have names, often based on the city or area where they were found. This can make everything a bit confusing, so I’ll mainly just use numbers here. This year, as talked about by UKHSA, the primary culprit is a rise in GII.17.

Symptoms/presentation

Noro is interesting as it frequently presents as something known as ‘Gastric flu’. This means that initial symptoms are often linked to a headache and feeling generally unwell, potentially with a fever. So, not just the diarrhoea and vomiting that people often think of associated with this virus.

That said, you also get the perfectly well to sudden projectile vomiting type of presentation, which is what people think of. Norovirus is the reason I once sat at a train station and vomited on my own shoes, as it just came out of nowhere. There is often a very short, intense spike in temperature, and then it is upon you. This form of intense and sudden presentation is just one of the reasons for the transmissibility of this particular virus. The lack of warning means that it is almost impossible to get away from others, and you won’t have ‘taken to your bed’ before the acute symptoms start.

It is worth noting that as well as these differences in adult presentations, presentations in young children are often also different, with more diarrhoea rather than vomiting. This means that Noro in young children can slide under the radar until adults caring for them then start to feel unwell.

The incubation period is pretty short (a couple of days), and so transmission windows in close quarters can be pretty intense. The duration of illness in most people is also pretty short, although symptoms tend to come in waves, and so it can be difficult for individuals to predict in some cases when it will finally be over. All of this is true for your standard healthy immunocompetent adult, but it is worth remembering that in both children and immunosuppressed adults, presentations, severity of illness, and length of infectivity can be very different.

Diagnosis

Most diagnoses of Norovirus within the community are going to be based on symptoms and presentation, as in most cases, any management is going to be symptom relief by maintaining fluid balance, etc. More specific diagnostics therefore only tend to be undertaken within healthcare environments, where it is important to know viral details to help inform risk assessment linked to transmission, as well as to monitor recover and inform epidemiology (what strains are spreading and if any of them are cause more severe disease).

There are many possible ways to diagnose Norovirus in the lab, from routine diagnostics using molecular methods and immunoassays, to how people are looking to diagnose using Norovirus in areas like care homes in the future using smart phones and other novel methods.

In terms of immunoassays, there are a couple of commonly used tests. The first are lateral flow assays (LFA), which most of us will be familiar with in terms of the lateral flow assays used for SARS CoV2, and the principles are similar. Enzyme immunoassays (EIAs) follow similar principles but are usually undertaken in the lab with many samples being processed at the same time, allowing much more widespread testing to be undertaken.

Which diagnostic test is most appropriate depends on how frequent cases are. In outbreak or high prevalence settings, then EIA has sufficient sensitivity to detect most cases. If circulating levels are not very high, i.e. outside of the standard season or outbreaks, or in high risk settings where missing cases could have severe patient impacts, such as some healthcare settings, then most publications suggest molecular methods are the most appropriate way to test.

The molecular methods listed include isothermal amplification, with Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) being a common method that was recognised during the pandemic for detecting SARS CoV2, and can be used outside of the traditional lab environment. I, in fact, validated a LAMP test for Noro when I was a trainee, so it’s been around for a while. The other listed is high throughput sequencing (HTS), which is a much more demanding technique requiring specialist skills and equipment, but also gains you all kinds of info, including that linked to strain and transmission data.

The most common molecular diagnostic test for Norovirus in high-risk settings is actually via polymerase chain reaction (PCR). This will usually target roughly a 130 base pair section of the Norovirus RNA genome out of the (on average) total 7500 base pairs of the virus, roughly 1.7% of the genome. This target area will usually enable differentiation between the common GI and GII species, which helps with monitoring and is chosen based on being present in all of those types in order to maximise sensitivity. Further differentiation into genogroups requires HTS but is often not needed outside of outbreaks and public health level epidemiology.

Spread

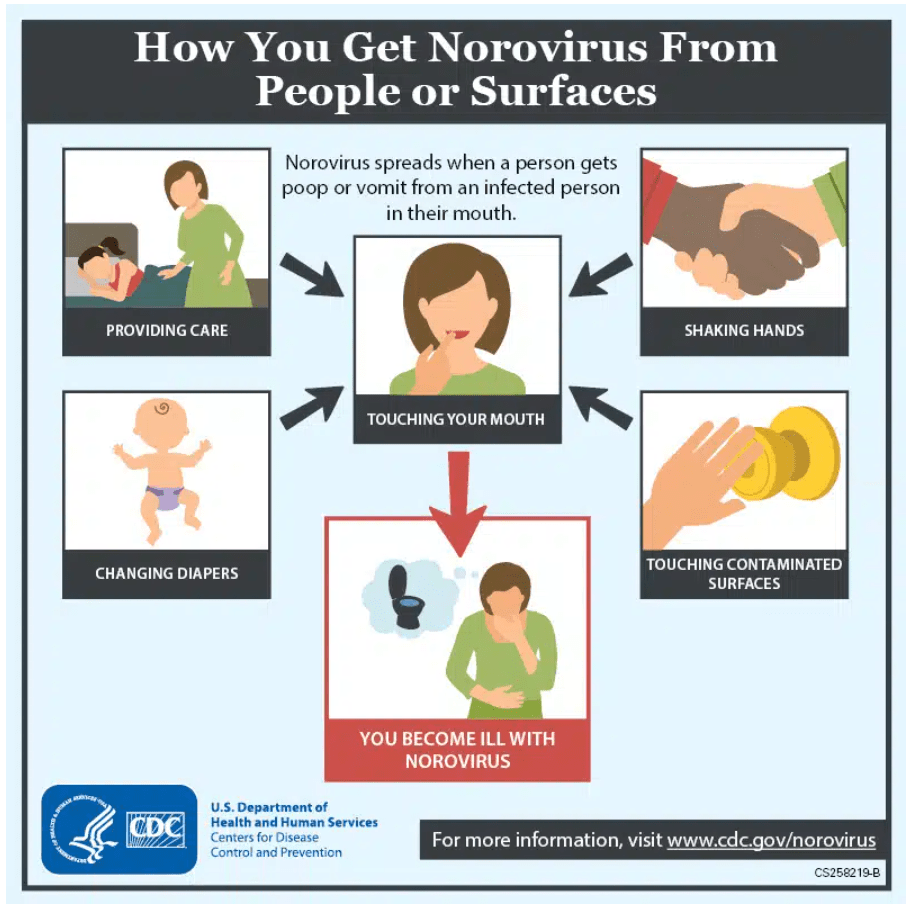

Norovirus is traditionally thought to be spread via what is known as the ‘faecal-oral’ route. That means that bits of poo and diarrhoea end up being swallowed by the person who then gets infected. This is because if someone has diarrhoea and goes to the bathroom, they will have up to 100,000,000 copies of the virus. This can then land in the area of the toilet, especially if the toilet seat isn’t closed on flushing, contaminating the surrounding area for anyone who goes into the bathroom and uses it afterwards. If someone then enters that bathroom and is susceptible to the virus, it is thought you then only need to swallow 10 – 100 copies of those 100,000,000 to become infected, and so only a very little is needed to spread the virus onward.

This isn’t the only route however. One of the issues with the acute vomiting phase of Noro is that someone vomiting can also vomit 30,000,000 copies of Noro. As the vomiting can be projectile, and come with a lot of force, this is ejected at high speed and can form what is known as an aerosol. This means the invisible vomit ‘cloud’ can hang around in the air for some time after the original vomit, meaning that anyone walking into the room where the vomit occurred for some time afterwards, or is present when it happens, can breath in the virus, and thus get infected that way.

As people can be infectious for some time after they’ve had acute infection (at least 48 hours) or when they have initial gastric virus symptoms before becoming acutely unwell, spread can commonly occur due to contamination of food products prepared by those infected. The common example is self catered events, such as weddings and birthday parties, where someone made a load of food on the morning and didn’t start to feel unwell until later in the day. 24 – 48 hours later a lot of the guests then suddenly start to feel unwell. This is a route via which lots of people can get sick from a single event and is known as a point source. Hand hygiene is always key, especially so when dealing with food, but the viral loading of people who are unwell with Norovirus means that avoiding being involved with food may be the only option, as there may just be too much virus present on hands etc to remove all of it easily.

The final route to consider is indirect spread. All of the circulating virus that’s in the air or in water droplets from the toilet flush, then will eventually come down and land on surfaces. Therefore those surfaces end up having a lot of virus upon them, and the virus, as non-enveloped, can survive on surfaces for some days. This means that then interacting with those surfaces can be a transmission risk, and so cleaning, and again hand hygiene, is really key to stopping ongoin spread.

Outbreaks

As those infected can be become unwell suddenly and spread lots of virus in a short period of time, Norovirus can be difficult to contain. Once an event occurs, all of the various transmission routes mean that Norovirus outbreaks can be difficult to control, and management is based upon rapid identification of cases and, if in hospital or even on a cruise ship, restricting contact to other people in order to reduce risk of spread.

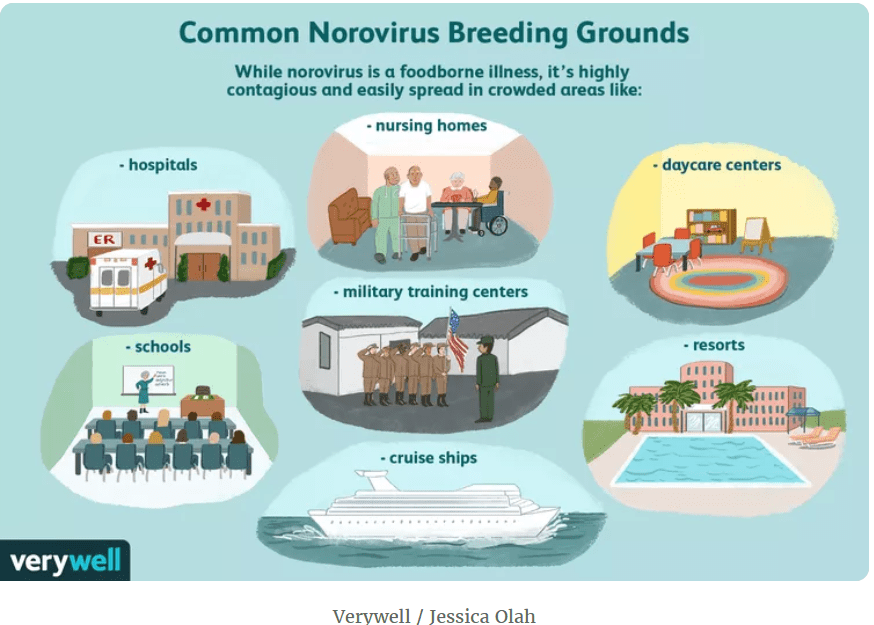

The biggest issues occur in the kind of areas where lots of people get together, high densities of people in physically confined areas. Everywhere from military training camps to schools and nurseries can be affected. As mentioned before, centres where people may present in atypical ways due to age or underlying condition can also make it more complex to contain infections and prevent spread. Hospitals have high population densities with restricted space for movement, combined with patients that are high risk as they already have conditions that impact immune function or make them more vulnerable.

Outside of traditional health and residential areas, such as care homes, cruise ships are at high risk as passengers can feel fine when they get on board and then experience symptoms in a confined space, with little room to spread out.

Even once recovered from symptoms, some of the passengers are also likely to continue to shed the virus (one adult study suggested for 182 days) and therefore some of those who get sick early on and recover may continue to be a silent source and risk for other passengers if they don’t have good general hygiene practices.

It can also be a challenge to decontaminate some of the surfaces, as they are often predominated by soft furnishing where it can be difficult to use cleaning agents with sufficient activity as Noro can be resistant to disinfection and present in such high loads it can be hard to remove. This has led to the surfaces in cruise ships being a continued risk even when all of the original passengers have departed and a completed fresh set has boarded.

Seasonality

Norovirus outbreaks are seasonal, with the peak occurring in the winter months. This is partly because, as humans, we tend to spend more time indoors in close quarters with each other during the colder months. We get together for the festive season, and because the nights draw in earlier. This means that we tend to spend more time in higher density interactions than in the summer, where we might be out eating alfresco or going for evening walks, or in my case, cocktails. We also tend to travel to other households and cook for each other as part of the seasonal festivities, which means the food borne route definitely comes into play. Finally, as temperature and humidity impact on the indirect surface route, environmental conditions mean that the viruses survival on surfaces at this time of year is probably more prolonged. Norovirus never really goes away, but the number of cases definitely spikes during the winter.

Strain variance/immunity

The UKHSA mentioned that one of the reasons that there may be more Norovirus cases around now is because one of the current predominant strains is GII.17. The chart below is linked to circulating Norovirus in China, so not the UK, but you can see, even over a few years, how the levels of different circulating strains changes, and that within years there are normally a few strains that co-circulate with a predominate strain type.

GII.17 is a less common strain and so many people will not have experienced it recently, if at all. If you haven’t had GII.17 before you won’t have immunity and therefore are susceptible to infection. Even if you have had GII.17 before, one of the reasons control of Norovirus is hard is that immunity is short lived. Even if you have experiences GII.17 before, therefore, the data shows that immunity lasts for anywhere from 6 months to 4 years, and therefore only relatively recent infection is protective. Finally, there is no cross strain immunity, so if there are three circulating strains of Norovirus in a season, unless you have experienced each of them in the relatively recent timeframe, it is possible to get multiple episodes, 1 from each strain, in a short period of time.

Prevention/Actions

Norovirus particles retain infectivity on surfaces and are resistant to a variety of disinfectants. This means that not only direct transmission routes (such as person to person) but indirect transmission via surfaces can be important. Interventions therefore need to take into account all of these different routes. Some common recommendations include:

- Hand hygiene with soap and water (alcohol gel is less effective as Noro is a non-enveloped virus)

- Staying away from other people until 48 hours after symptoms have ceased (as you often get a second wave of symptoms which increases risk of spread)

- Avoid cooking or preparing meals for other people until at least 48 hours after symptoms have ceased, and ensure good hand hygiene when you re-commence

- Cleaning with disinfectants (bleach etc at home) may be required, and multiple cleans may be needed due to the amount of virus present

- Time cleaning so there is enough time for any virus in the air to settle on the surface, so a re-cleaning after 2 hours will probably be needed

- Avoid going into a space where someone has vomited for 2 hours if possible to reduce the risk of inhaling virus

- Ensure you are aware that Noro can present with gastric flu type symptoms, headache and temperature, before gastric symptoms start, and so be weary of seeing high risk individuals if you have any symptoms present (especially those in hospitals or immunocompromised)

Due to the challenges with short lived immunity and high viral loading, you won’t be able to avoid getting Norovirus into confined areas and high risk settings, so rapidly identifying when you have cases and making sure that your interventions enable you to stop secondary spread is key. If you get sick, stay home, ensure you keep hydrated, and don’t let the virus fool you into thinking it’s done when you are feeling that little bit better on day 2, it’s Noro’s way of tricking you into going back out into the world an spreading it further. The queen of the gastric viruses is super clever and so we need to be even smarter to prevent her spread.

All opinions in this blog are my own