I’ve been having trouble sitting down to read actual paper books for a while now. The pandemic has my mind kind of worn out and, although I always used to have 4 or 5 paper books on the go at one time, right now I don’t have a single one. That’s not to say I’m not still getting my fiction/non-fiction fix. It’s just that right now it’s happening via audiobooks as I can just close by eyes and be transported.

This brings me onto a slightly new thing I’m going to try out: reviewing and giving some love to books that have science within them to aid that escape rather than making me irritated. I read the whole of the Newsflesh series by Mira Grant a few years ago at the suggestion of the wonderful Dr Claire Walker. As part of my insomnia strategy, I’ve rediscovered it and my love for the science within it.

The Newsflesh series consists of three main novels: Feed, Deadline and Blackout, as well as some short fiction.

Mira Grant describes the premise of the novels as:

“The zombie apocalypse happened more than twenty years ago. Contrary to popular belief, we didn’t all die out, largely because we’d had years of horror movies to tell us how to behave when the dead start walking. We fought back, and we won…sort of. The dead still walk; loved ones still try to eat you if you’re not careful; the virus that caused the problem in the first place is still incurable. But at least we lived, right?”

Nothing is impossible to kill. It’s just that sometimes after you kill something you have to keep shooting it until it stops moving

Mira Grant, Feed (Newsflesh Trilogy, #1)

Most zombie fiction is either set during the rising itself, that moment when the dead rise, or during a post-apocalyptic future where the worst of humanity is on display. Within the Newsflesh series, and especially Feed, this isn’t the case. It’s set 26 years after the rising in a world that lives with the ever present nature of having the undead on your doorstep. This is partly because of the way the rising occurred.

The Virus

As in most zombie fiction, the rising was caused by science that went wrong. In this case a modified virus known as Marburg-Amberlee (Marburg EX19), invented by Daniel Wells, was designed to cure leukaemia. It was first tested on Amanda Amberlee, a young leukaemia patient in Colorado, and it succeeded in curing her, after which it remained dormant in her cells and those of others given the cure. A second genetically modified virus was also being developed, known as the ‘Kellis cure’/’Kellis flu’. The aim of the Kellis cure was to provide a universal cure for the common cold. It contained a mix of coronavirus and rhinovirus proteins, with a fifth man-made protein that was designed to increase the virus’s ability to invade. When the Kellis cure is stolen from the research lab, where it is being developed by a group of activists who believe that this universal cure is being ‘held’ from the world and should be freely available, disaster occurs. The activists believe that the virus should be freely available to aerosolise the virus. The two RNA viruses underwent a combination event in those humans who had been treated with Marburg-Amberlee initiating a new infection, a virus now know as Kellis-Amberlee.

Now every mammal on the planet over 40lbs can convert into a zombie on reactivation of the latent virus in their cells. This can happen as a result of trauma, death or, like many latent viruses, due to failure of the immune system.

The World

This is the truth: We are a nation accustomed to being afraid. If I’m being honest, not just with you but with myself, it’s not just the nation, and it’s not just something we’ve grown used to. It’s the world, and it’s an addiction. People crave fear. Fear justifies everything. Fear makes it okay to have surrendered freedom after freedom, until our every move is tracked and recorded in a dozen databases the average person will never have access to. Fear creates, defines, and shapes our world, and without it, most of us would have no idea what to do with ourselves. Our ancestors dreamed of a world without boundaries, while we dream new boundaries to put around our homes, our children, and ourselves. We limit our potential day after day in the name of a safety that we refuse to ever achieve. We took a world that was huge with possibility, and we made it as small as we could.

Mira Grant, Feed (Newsflesh Trilogy, #1)

I think we’re all living in small worlds right now, as I write this on the sofa during yet another lockdown. The think I loved when I first read the novels, and actually love even more re-discovering them in a lockdown world, is how society has adapted to answer the challenges of infection.

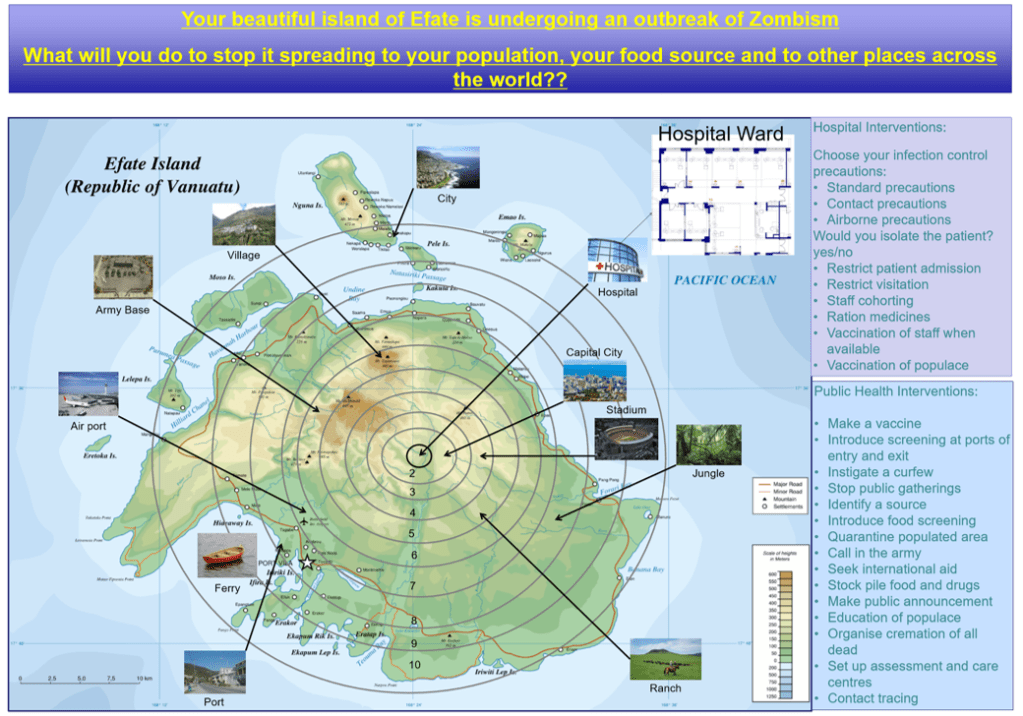

All areas of the country (it’s set in the States) are split into hazard categories. If you want to live in an outside space, where mammals could roam and it’s harder to control the movements of the walking dead, you have to accept higher levels of Infection Prevention and Control. Every car door has an antigen test that makes sure you are not in active viral replication before it will open so that you don’t risk fellow passengers. Every door into a home has the same risk. The world is split into those who have completely locked down and live for all intents and purposes an entirely virtual life. Whilst others, determined to have the right to maintain their freedom to keep animals such as horses, or other life styles choices, put their lives at risk to do so and also potentially risk others. Entire areas of the country have been declared ‘lost’, as the movements of the undead cannot be controlled. If you go into high-risk zones, all your clothes must be destroyed or, in less restrictive zones, sanitised whenever you leave the house. Every time you go outside you must be washed with dilute bleach on return. The rules are the law and following them is not supposed to be optional, although, as we are currently seeing, there are always those who will fall into the extremes of the two camps.

The Truth

The other thing that really resonates right now is the distrust of the media. During The Rising, the news is felt to have let down the public by being too much controlled by governments and institutions. The books themselves follow the Mason siblings, reporters Georgia and Shaun, as well as their news crew covering how a presidential election is run in this new world.

News is done differently in this new world because of the reaction to the number of deaths that were caused by the slow response of traditional media to covering the rapidly changing situation. Information is delivered by:

- Newsies (of which Georgia is one), who aim to deliver neutral fact-based coverage of the news via blogs and websites.

- Irwins (like Shaun Mason which are named after Steve Irwin), who seek to educate and entertain by going into areas that are off limits to non-reporters in order to give a true view of the world.

- Stewarts, who aim to collate and curate the reports of newsies, pretty much a ‘one site for all things’.

- Aunties, who share personal stories, recipes, and other content to keep people happy and relaxed.

- Fictionals (like Georgette “Buffy” Meissonier), who write poetry and fiction in order to explore everything that has happened to humanity since the rising.

One of the things that I currently worry about is how we will rebuild the trust and faith in science that may have been damaged by science becoming so politicised during the current pandemic. Although, in many ways, we’ve also seen the damage that going to individual blogs and echo chambers can do to the concept of evidence-based science. Re-engaging with the series right now does make you think about how difficult it is to communicate widely, and how important scientists having conversations across boundaries is.

In (not so, this post is longer than it should be) short, if you haven’t read Feed then you should. Read it because the virology is sound, and the Infection Prevention and Control makes me super happy. Mostly though, read it because it may give you a different lens through which to see our current situation, as well as being super entertaining.

All opinions in this blog are my own