It’s the most wonderful time of the year! It’s time for the annual Environment Network meeting, where we get together to talk all things environmental microbiology; sharing new research and experience to improve practice. And your guide for the conference this year, live blogging the morning session, is the token immunologist in the group, Dr Claire Walker.

What is the environment network?

Before we get onto todays’ content, a little introduction to what the Environment Network is.

The Environment Network works to support people in clinical, engineering and scientific roles who are interested in environmental infection prevention and control (IPC) and/or the built environment

Do you want to know more about what to do with your water screening and air sampling results? Are you keen to understand the evidence behind equipment cleaning and the role of the environment in healthcare associated infection?

Then welcome to the Environment Network!

This is a network for people in clinical/scientific/engineering roles within the NHS and other associated organisations who are interested in the role of environmental infection prevention and control in preventing infection.

The aim of the network is to support infection prevention and control professionals involved in commissioning, environmental audit, water, air and surface testing within their Trusts. By working together we can share best practice between Trusts; as well as circulating the latest evidence and discussing personal experiences.

What are the aims of the network?

- To support the development of member networks

- To provide events where shared learning can be supported

- To permit sharing of experiences and best practice to improve clinical interventions

- To support and share research in order to achieve improvements in evidence based practice

What is our remit?

- Environmental testing and monitoring within healthcare environments

- Environmental audit and risk assessment

- Surface decontamination

- Ventilation within healthcare environments

- Water management within healthcare environments

- Environmental outbreak monitoring and control

Check out the website for more details: https://environment-network.com/

On to today. First up we have Gavin Wood, an authorising engineer for water who acts as an independent advisor to Trusts. He is covering the fascinating topic of water associate outbreaks and what we can ask of our water safety groups during an outbreak. There should always be a policy which covers how to organise the estates teams and the water safety groups – covering who is responsible for each area during the outbreak. Regular outbreaks are caused by organisms like Legionella and Pseudomonas, but might include non-tuberculosis causing mycobacteria. Detection of these organisms during routine screening is reported to the water safety group to assess potential risk. Most pathogens that we look at will grow within a certain temperature range, so maintaining cold water as cold, and hot water as hot is essential. What we really don’t want is warm water stagnating in the system as the pathogens can thrive in it. On top of this, we need chemical control of organisms – mostly silver and copper ion systems. Stagnant areas of warm water are pockets where the pathogens might thrive so flushing the system and chemical controls are key in maintaining a healthy water supply in hospitals. Controls that are effective for indicator organisms that we routinely test for, like legionella, tend to be effective for any other outbreak organisms. In an outbreak situation the first port of call is the Legionella risk assessment which considers the efficacy of temperature and chemical control. After this, in line with guidance, all trusts should refer to their Water Safety Plan which is contains the detail on actions to take when results are outside the expected limits. Most of the time the authorised engineer already has the answers because the system is repeatedly routinely tested.

Like any system in a hospital, it is vital that the risk assessment and training is up to date. As Gavin says if we haven’t covered everything in the risk assessment, and if the water policy hasn’t been recently reviewed then the whole system is vulnerable. External audit by authorise engineers ensures the system remains optimal. Investigation of an outbreak focuses on the patient pathway – where has the visitor or patient been on their journey through the hospital. This process finds the clues to identify the source of the environmental outbreak. Surprisingly one of the main pieces of evidence comes from review of training and competence records, is everyone appropriately trained and acting in accordance with policy. If in doubt, going an witnessing monitoring and maintenance tasks can provide essential information in a high pressure outbreak situation. Gavin drives home how important practice is in this – we need this information as much on a random rainy Tuesday as much as we need it during a Legionella outbreak!

Our next talk comes from Karren Staniforth from UKHSA. She is a clinical scientist and UKHSA IPC specialist adviser, and is talking to us about the pros and cons of different outbreak investigation techniques. Karren invites us to imagine painting a busy ward in different colour 10cm squares, every single surface with a cotton tip swab. Imagine how long that could take and just how many squares you would end up with! Even if you took 200 samples, how many squares have you failed to test? Usually we can only take 20-40 samples…. So even if they all come back negative, it doesn’t necessarily mean there isn’t an organism there – its just that the sampling didn’t find it. The chances of going in and finding nothing is quite high, but if you put a patient in that room for a week, they will almost certainly find that organism (not that we recommend that as a testing method!).

Karren reminds us that reading environmental plates is quite an art and different from clinical samples, it’s a different skill and guidance from experts is essential. Clinical diagnostic laboratories aren’t accredited to process environmental samples and the staff aren’t trained to process and analyse this work. Commercial companies can come and do testing for you, and they are extremely good at routine work. Bespoke work is harder to commission, and that’s where knowing the network can really help! So if you have an outbreak of something unusual, it’s hard to find the information on what level of environmental organisms – like aspergillus – are ok, and what constitutes a danger to patients.

The questions becomes, what type of samples do we want to take and why? We need to understand basal levels of indicator organisms to work out when to act. Building on what Gavin has shared this morning, you need to look – really look- at what is happening in your environment. Karren reflects on how useful an audit can be but we don’t go into an outbreak with the information already in front of you, so your audit probably won’t ask exactly the right questions. Epidemiology provides the answers – which organisms and then which patients are affected, where and when? Identifying common exposures can be easy when infections match case distribution e.g. sequential patients with the same infection in the same room. However some are less obvious like laundry delivered to multiple sites causing infection clusters which are miles apart or commercial products that might only impact high risk patients in very low numbers, but at multiple sites across countries. This can be exceptionally difficult to trace. Though remember not every exposure results in colonisation and infection, and even if exposure is universal some patient groups are more likely to develop infections than others.

Knowing what kind of sample to take is essential, especially when sample numbers are limited. Negative results can be just as useful as positive results – and identifying the source of the outbreak is as much detective work as it is learning to read plates! Karren reminds us – ‘You don’t always need sampling, somethings are just WRONG!’.

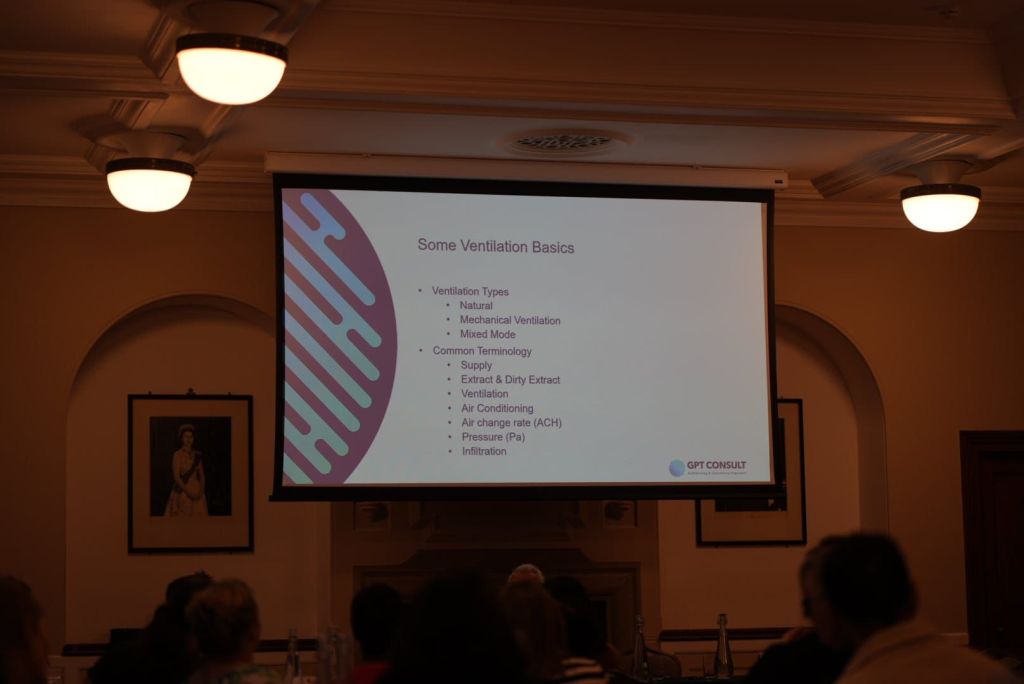

To close the first session, we have Louise Clarke who knows everything there is to know about proper ventilation. Ventilation is essential the movement of air within a system. The law tells us we must provide ventilation under the Healthy and Safety at Work Act, and building regulations set a minimum standard for ventilation. The main reason for good ventilation is to have a safe and comfortable environment; to remove odours, to control temperature and importantly to protect from harmful organisms and toxic substances. We have natural ventilation (like opening a window!), mechanical ventilation which pushes air around the building and a mixed mode – a combination of the two. The preferred method for ventilating a hospital remains natural ventilation, something which really shocked the group. It might work well on a windy day but it certainly doesn’t cover all areas and some times of year, like winter, it’s really no good at all.

Like Lou says, simple is best. When we talk about ventilation, we need to ask what is the issue we are looking at? Human elements are usually a key element to understanding problems in ventilation – you need to think about when the issue arose and who was involved? Often there is a significant time lag between the problem starting and it’s detection in real time. You can be left scrabbling around for details long after the issue began. Lou walked us through the potential information sources to considering during an outbreak, including design records. Which tend to be a little less useful than you would imagine, considering they often tell you the purpose the room was designed for 30 years ago – perhaps not so relevant now! Echoing the sentiments of Karren earlier, one of the most important things you can do is go physically and take a look – not an audit, just turn up and use all your senses!

To kick off the session after a much needed cup of tea (Earl Grey, hot!) we have Dr Mariyam Mirfenderesky who is talking about the challenges of managing fungal outbreaks. Candidozyma auris (note the new name!) is probably one of the most difficult outbreak causing organism to manage. To help with this a Clinical Expert Reference Group was established in March 2025. Candida species are the dominating fungal pathogens of invasive fungal disease and account for >85% of fungaemia in Europe and the United States. Candidozyma auris was first identified in 2009 from a Japanese patient with ear discharge, and is a critical WHO priority fungal pathogen. It is fluconazole resistant and has a propensity to cause healthcare associated infection outbreaks. There are 6 independent clades, with clade 1 dominating in England. Mariyam walked us through the identification of the first neonatal case of C.auris from an eye swab – it was found in two infants, five weeks apart with no direct contact between the children. Fortunately both were colonisation with the fungus only. She then discussed the safety measures that should be in place to manage this difficult pathogen – particularly focusing on why the current cleaning protocols are insufficient to manage this threat. Her final points considered how to act when you detect C.auris – you must be decisive and act!

If you’d like to know more about C. auris, check out this blog post from earlier this year:

Next we have Dr John Hartley who is talking to us about investigating environmental surface mediated outbreaks – what you can’t see may still hurt you. Using the classic movie ‘the fiend without a face’ as a metaphor for IPC, John introduced the idea of modes of transmission between individuals. It feels like a simple problem, its just cleaning and handwashing after all! But we see there is a complex person-organism-environment dynamic system, and as John says, there is always a well known solution to every human problem – neat, plausible and wrong! John highlights the importance of continual surveillance and knowing ‘where the fiend is’. The controls are based on a four pronged approach – clean, replace, destroy or rebuild.

By way of a case study, John told us about his experience of managing adenovirus outbreaks in a paediatric BMT ward. This is a very common virus causing 5-10% of febrile illness in early childhood. Almost everyone has had it, and it can establish latency which can reactivate during BMT. More often it causes severe morbidity and mortality in these patients who can develop hepatitis. What you can’t tell is if the child caught adenovirus from the environment or if it has reactivated post latency. However, whole genome sequencing (WGS) can resolve 1-3 SNPs across genomes – its not like looking for a needle in a haystack, its rather like looking for a needle in the whole of Texas. But WGS can be used to confirm or refute cross infection events.

Of course the next question is, what can be done? Visual assessment is not a reliable indicator of surface cleanliness, John described the varied methods which can be used to detect adenovirus. Then we need to develop the right tools to manage it – including development of environmental PCR as a measure of cleaning efficacy by GirlyMicro herself! Finishing on a Dr Who reference to delight a crowd of scientists is always a win – even if it is comparing adenovirus to the scariest episode, the weeping angels! Of course, when monitoring adenovirus, the most important advice is ‘Don’t Blink’.

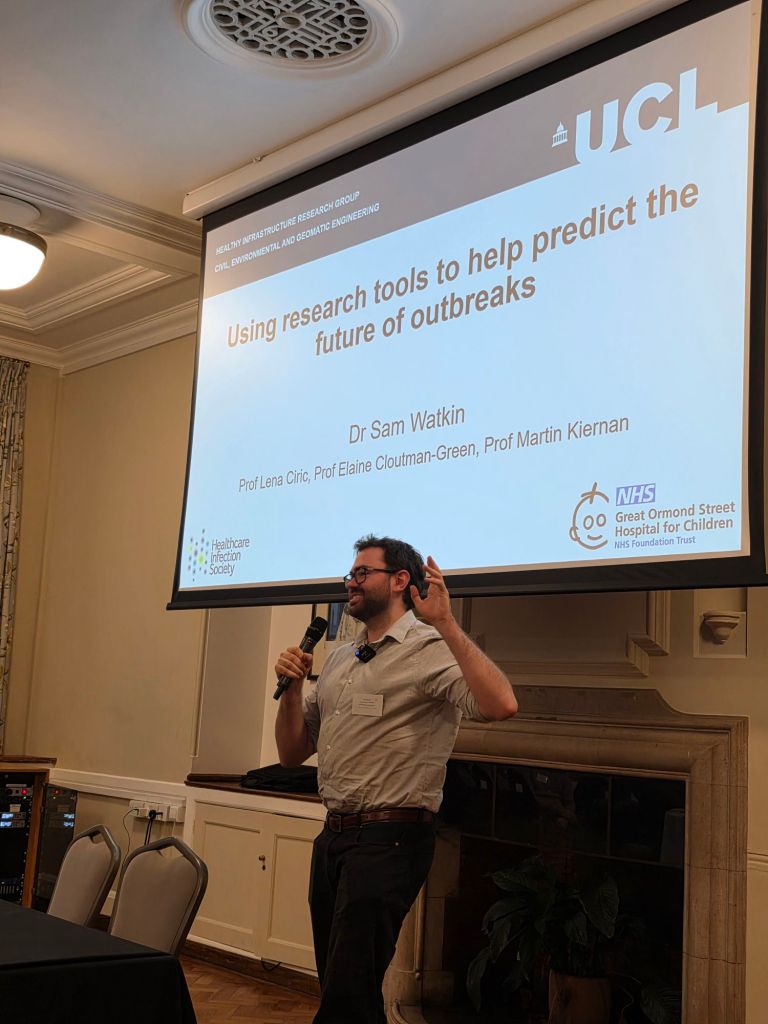

To close the morning session we have Dr Sam Watkin discussing research tools to help predict the future of outbreaks. Sam began acknowledging the current challenges facing preventing transmission of environmental organisms. In his PhD he aimed to identify how microbes disseminate through the clinical space, if the starting contamination site determined how is was disseminated and if the usage of space influenced microbial transmission risk. IPC is often retrospective to the aim was to develop research tools to allow the development of prospective knowledge. Sam used cauliflower mosaic virus DNA markers as a surrogate for pathogens, and followed its movement around two different units. It was shocking to see how far this benign organism could spread in such a short time.

I think if we take away anything this morning it’s that nobody likes the new name for C.auris, and death, death to recirculating air conditioning units!

The morning was followed in the afternoon by a series of case discussions in order to help implement the learning from the morning, help everyone get to know each other, and support the sharing of peer to peer learning. The case discussions this year included:

- Case discussion one (Facilitated by Dr John Hartley):

- Seek and remove: approaches to source control for environmental surface mediated outbreaks

- Case discussion two (Facilitated by Professor Elaine Cloutman-Green):

- How to implement a multi-disciplinary approach to investigation of water borne outbreaks

- Case discussion three (Facilitated by Louise Clarke):

- Interpretation of ventilation data and applying it to ventilation risk assessments

- Case discussion four (Facilitated by Dr Sam Watkin):

- Determining the role of equipment in outbreaks: how do you investigate?

- Case discussion five (Facilitated by Karren Staniforth):

- Introducing new cleaning process: what should you consider?

- Case discussion six (Facilitated by Dr Claire Walker):

- Choosing new equipment and furnishings: what questions should you ask?

It was truly inspiring to hear the buzz in the room that all of the discussion created. Thank you to Mr Girlymicro (Jon Cloutman-Green) for being in charge of photography, and to all of our speakers and facilitators for making the day happen. Also, massive shout out to Ant De Souza for pulling the day together, Angela McGee for making sure we all turned up to the right place at the right time, Mummy Girlymicro for running the reception desk, and to Richard Axell for supporting all of the tech on the day.

Now it is all over, the only thing to do is to tap our feet until we all get to meet again in 2026, although the presentations and discussion sheets should go up some time during 2025. Until then however, if you want to know more either head to the Environment Network website to look at info from previous years, or read some of the other blog posts linked to environmental IPC down below.

All opinions in this blog are my own