Friday just gone, 25th April, was World DNA Day. I’ve had a series of blogs that I’ve been playing around with linked to what DNA is, how we look for and investigate it and how we are exploring DNA in our everyday lives. Linked to this I’ve also got two book reviews coming where the world changes because of genetic testing and genetic manipulation. So this is the first of four part DNA bonanza.

I thought I would write these posts, because as much as artificial intelligence could change the way we live and is frequently discussed, we are all accessing DNA based testing more and more, with many of us not really thinking about how this too is changing the world in which we live.

I remember really clearly the first time I actively came across the concept of DNA, DNA testing and DNA manipulation. It was in Jurassic Park, when Mr DNA pops up at the start of the film to talk you through how they used DNA and cloning in order to make the dinosaurs. This film came out in 1993, I was 13 and I just remember how all of my class were queuing up to get tickets. It was the first film I really remember there being hype about, well that and Aladdin which was a different kind of seminal moment. It was the first film I remember watching and thinking just how cool science and scientists were.

In fact I talk about Mr DNA so much that the wonderful Mr Girlymicro brought me a Mr DNA Funko pop which lives on my desk at work and reminds me that the impression we make on people stays with them.

What does all this have to do with how we use DNA now? Well, in 1990 when Jurassic Park came out, the routine use of DNA, even in research, was still pretty much science fiction. The structure of DNA had only been described in 1953. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), which is the main way we investigate DNA, had only been developed in 1983, and was only starting to become more widely available in the 1990’s. When I started working within healthcare in 2004, we were only really just starting to move from PCR being something that was used in research to something that was common place in clinical diagnostics. The leap from there, to a world where thousands of us can swab ourselves at home and post samples off to be diagnosed with SARS CoV2 during the pandemic, or to get information on our genetic heritage, would have sounded like something that would only occur in a science fiction novel if you’d mentioned to me back theb.

Just a flag, this part one post has a lot of the technical stuff linked to what DNA is and how we investigate it. You may want to skip this post and head directly for part two if you don’t want to be reminded of secondary school science, but if you can bear with me I think it will help some of the context.

What is DNA?

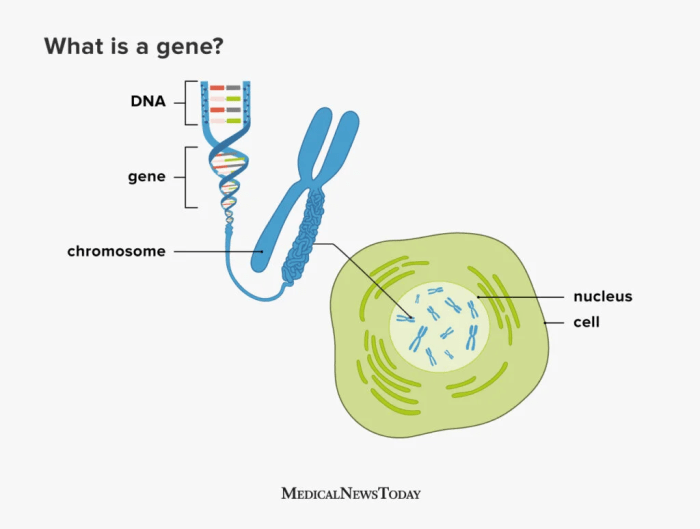

DNA, or to give it its full name Deoxyribonucleic acid, is commonly referred to as the building block of life. The structure of DNA consists of a double-stranded helix held together by complementary base pairs. The nucleotides that form the base pairs are adenine, thymine, guanine or cytosine. These nucleotides act to link the two strands together via hydrogen bonds, with thymine always pairing with adenine (T-A) and guanine always pairing with cytosine (G-C).

Sections of DNA then combine together together to code for genes, which are sections of DNA that work together in order to code for proteins, that then permits the expression of our DNA in physical form.

Genes are organised into chromosomes or packages of DNA. Each chromosome is formed from a single, enormously long DNA molecule that contains a strand of many genes, with the human genome containing 3.2 × 109 DNA (3,200,000,000) nucleotide pairs, divided into 46 chromosomes formed from 23 pairs (22 pairs of different autosomes and a pair sex chromosomes).

So how do we get from DNA to proteins? The specific sequences of nucleotides that form our DNA are arranged in triplets (groups of three). To turn DNA into protein, it gets transcribed into RNA (ribonucleic acid) within cells, with each of these triplets coding (translating) into an amino acid, which then get combined together to form proteins. The amino acids combined dictate what form and function the resulting proteins takes. Proteins then serve as structural support, biochemical catalysts, hormones, enzymes, and building blocks for all the processes we need to survive as humans.

Long and short, everything comes from your DNA, it’s super important, and is unique to you, but it’s structure is complex and there’s a lot of it in each of us.

How do we investigate DNA?

Now that we know about what DNA is, and how important it is for life, not just for humans but for all living things, it makes sense why so much time and energy has been deployed into understanding more about what it means for us as a species, as well as for us as individuals.

I’ve mentioned that PCR was first developed in the 80’s but didn’t really come into routine clinical testing until the 2000’s. What is PCR though and how does it work?

I often describe PCR as a way to look for DNA that is similar to looking for a needle in a 25 story block of flats sized haystack. The human genome is 3.2 billion base pairs, and we are often looking for a fragment of DNA about 150 base pairs in length, 1/21 millionth of the genome. It’s quite the technical challenge and you can see why it took quite a while to be able to move from theoretically possible to every day use. What makes it even more complicated is that you need to know what that 150 nucleotide fragment is likely to contain or where it is likely to be positioned within those 3.2 billion base pairs to really do it well. The human genome was not fully sequenced, and therefore available to us to design against, until the year before I started my training at GOSH, 2003. The progress therefore in the last 20 years has been extraordinary, and I can only imagine what will happen in the next 20 years. Hence the book reviews that will be coming as parts 3 and 4 of this blog.

So, how does PCR work? Well the first thing to say is that there are actually a number of different types of PCR, although the basic principles are the same. For example, there are some types of PCR that target RNA. There are also types of PCR that are used more frequently within clinical settings for things like SARS CoV2 testing, that are called Real Time PCR, called that as results become available in real time rather than waiting for the end of the process. It is for Real Time PCR that the small ~150 nucleotide fragment length is an issue. So all of these processes have their own pros and cons. Like many things in science, you have to use the right process to answer the right question.

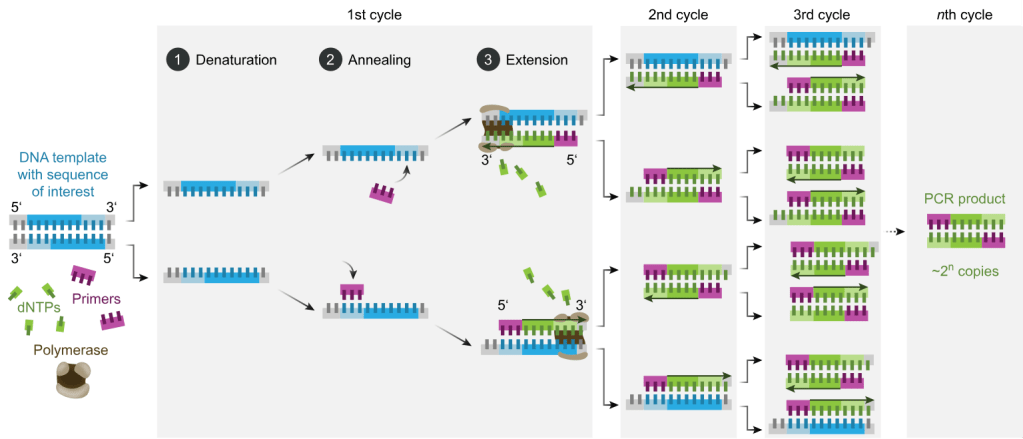

The basic principles shared between types of PCR are as follows:

Designing your primers:

Primers are the pieces of DNA that you design and make that will stick to your target piece of DNA you are interested in. The reason this works is because of the fact that the nucleotides that make up DNA are complimentary and so A binds to T, C binds to G. As DNA is double stranded you can design your primers (your equivalent to the magnets to find you needle in your haystack) so that they will bind to your specific target (the piece of DNA you are interest in). If you want to have your primer stick to a piece of DNA sequence that reads AAG CTC TTG, you would design a primer that ran TTC GAG AAC using the complementary bases, make sense?

You design one set of primers for one strand, this is called your forward primer (moving from 5′ to 3′), and then you design your reverse primer at the other end of your target for the opposite DNA strand (moving from 3′ to 5′). Doing it this way means that when you start your PCR process you end up with complete copies of your target. You will then successfully have pulled the needle from your haystack using you targeted magnets.

Undertaking the PCR:

Once you’ve got your primers (which you can just order in once designed) you can then get onto the process of the PCR itself. You combine your sample that you think might contain the DNA target you are looking for (be that human, bacterial, environmental etc) with the reagents (chemicals) that you need to make the process work all in a single small tube. This tends to be a delicate process that needs to be undertaken at controlled temperatures as the protein that runs the process (Taq polymerase) is delicate and expensive. To do this we combine:

- DNA Template: This is the sample that contains the DNA target you want to amplify

- DNA Polymerase: Almost always this is Taq polymerase which is used due to its heat-stability as it originates from a bacteria that lives it deep sea vents. This allows it to function at the high temperatures required for PCR and is used to make the new DNA copies

- Primers: These are the short, synthetic DNA sequences that you design to attach to either end of your target DNA region. These then allow the DNA polymerase to add nucleotides to create the new DNA strands

- Nucleotides (dNTPs): These are single nucleotides (bases) that are then used to build the new DNA strands (adenine, thymine, guanine, and cytosine)

- Buffer Solution: This solution provides the optimal conditions (pH, salt concentration) for the enzyme to function properly

Once you have your reagents you then put them on a platform that heats and cools for different steps to allow the enzymes to work and for the new DNA strands to be created:

- Denaturation: The double-stranded DNA template is heated (typically to 95°C) to separate it into two single strands. This step ensures that the primers can access the DNA sequence of interest

- Annealing: The temperature is lowered (typically to 50-60°C) to allow primers to bind to their complementary sequences on the single-stranded DNA. This is the step where your magnets find their needle

- Extension: The temperature is raised again (usually to somewhere around 72°C, the optimal temperature for Taq polymerase activity). Taq polymerase extends the primers by adding complementary nucleotides based on the DNA sequence to create new copies of the original DNA target

These three stages are repeated in cycles, typically 20-40 times, which results in thousands and thousands of copies of the original target to be created, so that eventually your 25 storey haystack is made up of more needles than it is hay, and therefore it is easy to find what you are looking for.

Interpreting your results:

At the end of your PCR step, if you are using traditional PCR, you run what is now called your PCR product or amplicon (the things you’ve made) through something called a gel. This is just a flat jelly made of agarose (or seaweed) which also contains a dye that binds to DNA and allows to separate your DNA based on size. This allows you pick out where you have samples that have the massive amplification you are looking for, as you can see it as a band within the gel. If a band is there and the right size (as you know how big your target was supposed to be) this is a PCR positive.

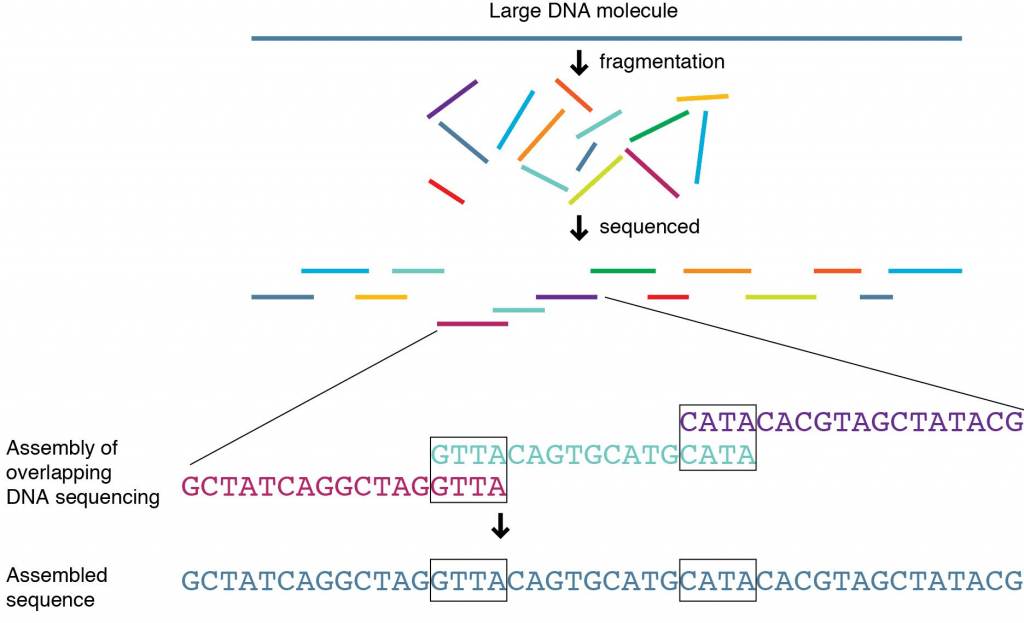

If you need to know more detail than whether something is present or absent, for instance if you need to know not just that a gene is there but which variant of a gene is present, you need to be able to tell what the nucleotides that were added between your two primers actually were. To do this, you will follow up PCR with a process called sequencing.

You take your target PCR’d section and then put it through a process to work out what the nucleotides added were. This involves doing the PCR process again, to make even more copies, but the nucleotides added into the reagent mix have fluorescence attached so you can tell which ones have been added during the PCR process. G’s often produce a black colour when hit by light, A’s green, T’s red and C’s blue.

For our original sequence we talked about, AAG CTC TTG, the sequence would read Green, Green, Black then Blue, Red, Blue followed by Red Red Black. Colours are then back interpreted into a DNA sequence (a series of letters) and there you have it, you know what the DNA is between your primers and you can then interpret your sequencing result. If you have large fragments of DNA you are interested in, you may have to do this in overlapping segments and put it back together, something like a jigsaw, before you can get your answer, but the basic process is the same.

What can DNA tell us?

As I’ve said, the search for DNA and specific genes has become an increasingly normal part of providing diagnostics in healthcare. Most of us will have sent off a swab for a PCR at least once during the COVID-19 pandemic. PCRs are frequently used in my world of infectious diseases to see if a bacteria is present or absent. They are also used so that I am able to see if a bacteria will respond to an antibiotic, by seeing if they carry antibiotic resistance genes, which can be crucial to getting patients on the right treatment at the right time.

Looking for specific variants of genes is also key to making sure that the treatments we give also don’t cause any unexpected consequences. A good example of this is when we use PCR and sequencing to look at genetic variants of a gene called MT-RNR1. A specific variant in this gene, m.1555A>G, is known to increase the risk of aminoglycoside-induced hearing loss. Aminoglycosides are a crucial antibiotic class that are used pretty widely, but especially in management of some conditions such as cystic fibrosis and certain types of cancers. A small number of people have a gene that makes them prone to something called ototoxicity as a result of taking these antibiotics, resulting in hearing loss. If we know a patient has this gene variant we can then choose to use different antibiotics, improving patient outcomes and avoiding a life long hearing impact.

Outside of screening linked to patients presenting with specific conditions, the use of DNA sequencing is being utilised more widely to look for genes or conditions before they even present with symptoms, in order to reduce time to diagnosis, and hopefully to be able to find patients and start management before they’re impacted or even present as unwell. A great example of this is the newborn screening programme that started last year. This screens newborns using the heel pricks of blood taken at birth so that rare diseases that could take months or years to diagnose by traditional means are picked up early in life, therefore allowing appropriate treatment to start earlier and hopefully saving lives.

How do we find out more about our DNA?

DNA is fascinating and I love knowing about it. It’s not just me though. In recent years there has been an increasing trend for people to send off their DNA for other purposes than to hospitals for clinical testing. I’m not going to say too much about this in part one, but it was this that really inspired me to write these posts in the first place and is the main focus of part two of this blog series.

Just a quick google however provides a wide number of different companies offering a variety of DNA testing services outside of the NHS (NB I don’t advocate for any of them):

- Crystal Health Group: Operates a network of DNA testing clinics, offering relationship testing and other services.

- 23andMe: Provides DNA testing for health, ancestry, and other personal insights.

- Living DNA: Focuses on both ancestry and wellbeing-related DNA testing.

- MyHeritage: Provides DNA testing, particularly for ancestry research.

- AncestryDNA: Company specialising in DNA testing for ancestry discovery.

The complication with all of this type of provision of testing is that outside of the clinical world in the UK, where testing should be undertaken in accredited laboratories and reporting of the results must meet certain standards, sending off DNA to private companies is much less monitored.

I hope you can see by some of the technical descriptions just how complicated these DNA processes can be. How time consuming, and how expensive to get right. There is also a lot of nuance about the different types of PCR, sequencing, gene targets, and results analysis that can be offered under the umbrella of ‘DNA testing’. Without the right people involved to make sure that there is embedded quality assurance challenges could arise, depending on what kind of testing is undertaken.

As stated in a recent Independent article:

As they’re based on estimates, I suggest treating home DNA tests as a fun investigation to get to know your family history a little better rather than a to-the-letter representation of everything that’s ever happened in your gene pool – Ella Duggan Friday 28 March 2025

https://www.independent.co.uk/extras/indybest/best-dna-test-uk-ancestry-b1944632.html

The devil for all of these things really is in the detail, and we’ll get into that detail much more in part two! For those of you interested in learning more about the history of DNA testing, I’ve included a talk below. Happy World DNA Day

All opinions in this blog are my own