Dear gentle reader, let me tell you a tale, a tale of a naive PhD student and of her nemesis, the notorious villain known as The Thesis. Grab a comforting beverage, as this tale is filled with both thrills and peril for your delectation.

The final 12 months of my PhD were tricky. I had simultaneously signed up to do FRCPath and a PGCert in education on top of thesis writing, which in hindsight was beyond stupid, but made a strange sense at the time. So I was writing not only a thesis, but a Fellowship of the Higher Education Academy (FHEA) portfolio as well, and trying to submit my thesis a year early in order to allow revision time for my final clinical exams. I’d also run into supervision challenges as my primaries vision of my thesis, both in the required level of content and how that content was presented, was different to mine. Needless to say, it was a bit a grim time.

Fast forward to my viva, I have submitted my thesis without supervisor sign off, and to be honest, there was a good chance I was entirely wrong and had set myself up for failure. The viva had lasted an hour, including having a cup of tea with my examiners. This is either a really good or hella bad sign, right? I’m standing outside the room whilst they deliberate, and I am seriously considering just running away as I’m in the midst of a full-on panic with my rational brain having entirely left the party. Suddenly, I hear them laughing, and I know that I am doomed. I’m about to just leave when the door opens, and they are standing there, staring at me expectantly. I have no choice, I enter the room to hear my fate.

The first words out of their mouths are “can you take a seat, we have some bad news for you and it’s probably better that you’re seated whilst we go through it”. At this point, I almost vomit, and it takes everything I have not to cry. I had been wrong. My primary was right, I’m a disaster, what was I thinking. I sit, and all I can think is that I just need to get out of this room and back to Mr Girlymicro, and the sooner I get it over with, the better. They look at each other and then at me, the external says “we have to ask for some changes and I’m afraid that they are substantial” they look at each other again pausing for what felt like forever before continuing “we need you to add an extra page of conclusions and it MUST NOT be more than 350 words”. They burst into laughter and shake each others hands and then mine. I stare at them blankly and ask them to repeat. When they are done laughing with each other they say, “also, when you have PhD students NEVER show them your thesis, show them a chapter of your thesis, that’s what a thesis should look like”. They then dump the examiner copies of my thesis into my hands to carry from the room so I can experience the weight….still smiling at each other, and the whole thing is over.

I therefore include my PhD thesis below not as an example of the thesis you should write, but perhaps as an example that is so long you might get away with a short viva and the examiners saying they never want to see it again. I also thought that this week I might include some of the lessons that that 12 month period taught me, as well as what I have learnt since from being both a supervisor and examiner.

Your thesis should tell a story, so be aware of what serves the tale

You may have a much better vision for your thesis than I did for mine, but whatever that vision is, it needs to involve telling your reader/examiner a coherent story. You may have done 20 small bits of work that you did because they were individually interesting, but when it comes to your thesis it’s time to put those together into chapters that read like you’d planned all of them together and a tale that hold logical progression from 1 chapter to another.

There are plenty of different ways to do this, and you can take any approach that makes sense for your work, but there are a few things to consider:

- Think about having a thesis structure diagram so how your work hangs together doesn’t have to be intuited by your examiners, but is clearly laid out

- Think carefully about the number of chapters and chapter order to ensure they are supporting the overall tale you are telling, be that of scientific discovery or adversity over failure

- Try to embed being clear about your why and impact throughout, especially if you are doing a clinical PhD. Be conscious about picking the points where you can make your ‘so what’ clear

- Rationalise what you should include to serve the story you are telling. You do not need to include every single thing you’ve done, in fact it could make it harder to read

Think about what purpose your thesis will serve

This one may sound a little weird, as surely everyone’s thesis serves the same purpose, to convey the work done during the PhD and provide a route for assessment. That is true. However, in terms of longevity, some thesis serve a different purpose. For me, as my research area is also in my area of work, my thesis is a manual I still go back to to remind myself of how to do pieces of work, such as decontamination validations. This won’t be true for some people. Some people write a thesis that will never be read again, and so the thesis is written to please their examiners as a primary function. Mine, as you’ve read, was less pleasing to my examiners, but acts as a reference text for me to this day, and so fulfils the purpose that I had in mind when I wrote it.

Know your process

We all work differently, but the more you understand how you work the more you will reduce your stress around thesis writing. Are you a, write it up as I go kind of person? Are you a, I need to have all the info to decide what my story it before I start gal?

My process was that, because I was still working clinically part time, I took a month for each chapter of my thesis. Week 1 I undertook a literature search and collated all the relevant papers, read them and made bullet points, week 2 I created figures and started writing, week 3 I finished writing the chapter, week 4 I edited and sent it out for comment. Repeat for 5 months, and I was pretty much done.

My PhD students are far superior to me, they are well read, keep spreadsheets of notes, as well as writing up as they go along. As I was balancing responsive IPC and my PhD that just never worked out for me. There’s no point in pretending to be in a category that you aren’t or wishing it were different. Discover how you work, acknowledge it, and then find a practical framework where you can use it to your advantage.

Do your research

Now we are getting the nitty gritty of what I had wished I had known before I started, and this part all comes down to research. There are a few things which I wish I’d invested more time in before I even started writing my thesis as they would have removed a bunch of the wall contemplation and anxiety, as well as saving a heap of time:

- There are lots of different ways to structure a thesis, and as long as you obey the broad university rules, the detail of how you do it is up to you. Spend time looking at other people’s, as the best flattery is to borrow, to identify the bits you like, the bits you don’t like, and find inspiration for what works for your way of thinking. All of the UCL ones are available online, and I’m sure many other universities are the same

- Learn how to make/edit writing templates, or find ones that are pre-done. This may be the old person in me but I just didn’t know enough about how to set up word or other document templates to auto generate lists. My poor friend came in at the end and spent 8 hours correcting my thesis so all of it would work and I didn’t have to manually change my indexing

- Find reference software that you like and spend time making sure your inputs are high quality and not missing details. The last thing you want to do for hours pre submission is to correct hundreds of incomplete references as you didn’t check on upload

- Know your university submission rules inside and out. You will hopefully never be in the position I was in, where I had to know what would happen if I submitted without supervisor sign off, but even so it is worth familiarising yourself. These rules will help you choose examiners, understand time scales, and be sure your thesis structure is acceptable. Best always to be prepared.

More is not always better

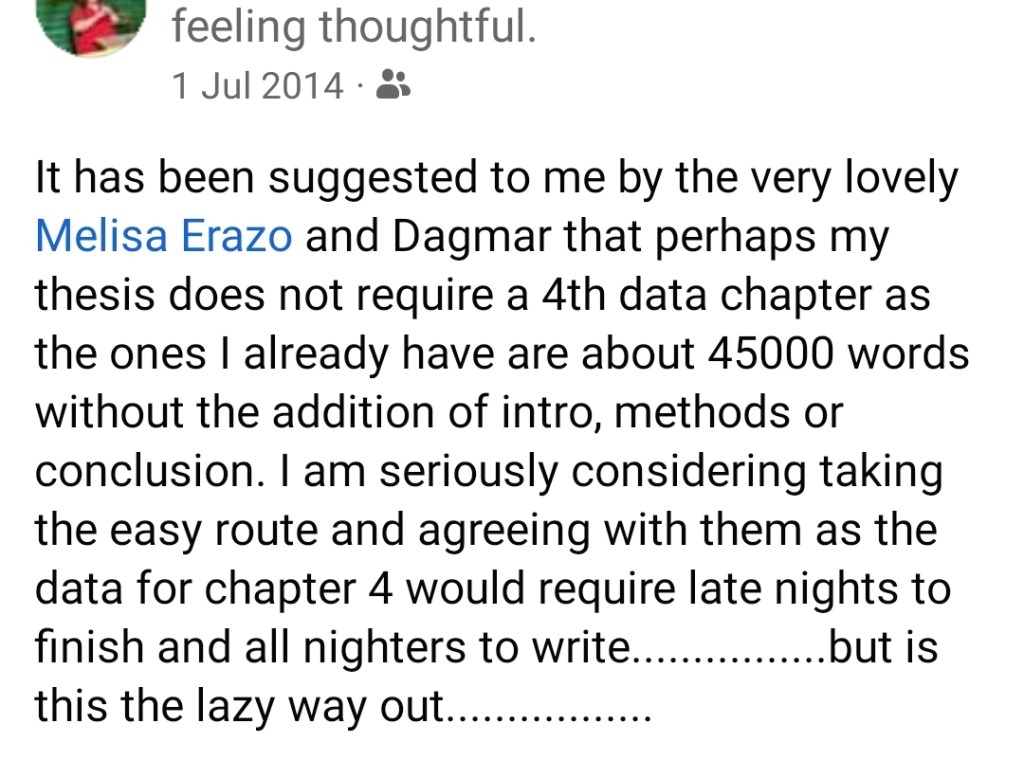

As much as my thesis was long at 95,000 words plus references, for a short time it looked like it might be even longer and I was going to struggle to keep it under the 100,000 word limit. I had an entire other data chapter to put in and just had a lot of self doubt about dropping it as I thought it was the ‘lazy’ option (BTW I often struggle as I think of myself as a pretty lazy person and so find it difficult to self check). The thing is, it didn’t serve my story, and I would have been adding it in just to show how much work I’d done. That really isn’t the purpose of a thesis so in the end I was persuaded to edit and drop it out. It was such a good call but required the help and support of others. Making sure that you are either able to do a brutal edit yourself, or can call in the support of someone else who can, will make your thesis so much better.

Find a critical friend

Which brings me onto having critical friends. These are the people you like and trust to tell you the things you may not want to hear but will make your work better. You need to find a couple of these who will read though and discuss your work with you, preferably ones who will also help edit as they go. You need people doing this who understand what you are doing and you have pre-existing relationship capital with, so it won’t destroy your friendship when they point out that something isn’t making sense and you haven’t slept for a week. Pre build these relationships ahead of time during your PhD, nurture them, they will stand you in good sted, not just for your thesis but for life.

Take advice, but have the courage of your convictions

Writing a thesis is like planning a wedding, once you mention it everyone will just start offering you advice. I understand the irony of this statement in the context of this blog post, but it’s true, and honestly no one is forcing you to read these words 😉 All of this advice can become very challenging, as the likelihood is that some, if not all of it, will end up being conflicting, especially if you have too much of it. It’s one of the reasons I suggest having just a couple of good critical friends, obviously in addition to your supervisors.

I would also suggest reviewing all of the advice you receive on the basis of three things before you take it onboard:

- The level of knowledge and experience of the person giving it you in the specific task you are doing – accepting a history PhD’s thoughts on your genomic thesis may not be that helpful, although they may inspire a new approach that could work

- Understand the drivers behind the advice – some people will give you advice just because they feel they have to contribute, and some people will genuinely want to help. Not all advice is benign, however, and so understanding the drivers behind it is key

- Evaluate whether the suggestion works for the way your mind works – some people will have really good suggestions that don’t work for the way you process the world or your vision – ideas are like dresses, the same ones don’t fit everyone

Be prepared to find your own way forward as you are the person who needs to write it. Keep enough of an open mind to accept a challenge that will lead to improvement, but don’t try to incorporate everything, otherwise you will lose your voice at the centre of it.

Be prepared for revisions

It’s so tempting to think that if you put enough time into your first draft that you will be saving time further down the line. The problem is that that is not always true. Sometimes, spending a lot of time on your first draft just means you go further down an inappropriate rabbit hole. You can lose not only lose a lot of time when you have redo it, but it can also become challenging psychologically to make the change. Think me and the Adenovirus chapter, unnecessary agonising occurred which took up emotional band width and time. In the initial structural work up phase, it is probably worth therefore getting early commentary before you are too attached to a specific approach, so that if you have to pivot you can do more easily.

The other thing to note is that it will always take you waaaay longer to edit than you anticipated. For most of us, we have never had to work on a document this long, and so don’t generally have good projection skills for the length of time it will take. You will also want so many more versions and edits of your thesis than of any other document you’ve done, as you won’t want all those spelling mistakes coming back as corrections, and I for one didn’t realising I would be on ‘final version’ 20 something.

Finally, your supervisors and others reading and editing it will take much longer to get it back to you than other things you’ve sent on because they also have to find larger chunks of time than they normally would. It is also worth knowing ahead of time how many times your supervisors are prepared to look at it, so that you make the most of the opportunities you have and pick the key moments for input. Make sure whatever time you think you’ll need for editing is probably tripled on your project plan.

Remember to take time to decompress

I write this as someone who quite literally lost her hair and developed a bald patch during her PhD, make sure you take breaks. Your brain is processing vast amounts of information during your writing up period and it is easy to become laser focussed. That’s good but it can also be trouble. You need to walk away from a piece of work to see the problems and the gaps within it. From a basic point of view, you will get to the point where you read what you think is there rather than what it actually is there, and that is no good to you in the long run.

So, from someone who didn’t and still lives with the physical consequences, make sure that both your mind and body are able to do what it needed of them by ensuring you rest. Sometimes, all you’ll need is a day in the lab away from the laptop, but some days you will need to have a long soak or a walk in the woods to enable your mind to see what’s right in front of it when you return. Also, I highly recommend booking a holiday between submission and your viva date so you walk into that viva room in the best physical and mental shape you can.

Your thesis is YOUR thesis

Your thesis, like your PhD is one of the few times in your career where the work should be entirely yours, and at the end of the day you will be the person sat alone in a room to defend your choices. I’m not advocating ignoring your supervisors, they will have huge amounts of experience and it is always worth getting the benefit of what they have to say. If the crunch time happens however you can’t use the ‘my supervisor told me to’ defence when you are sat in that room and looking your examiners in the eye. Your work has to make sense to you and be presented in a way that you can walk someone else through and defend it, there’s a reason a viva is called a defence in the US. So, as much as it’s important to get the best possible advice, input and support, when it comes to being in that room you are alone, and so you have to own the decisions you’ve made and the work you’ve done. You will come out of that room all the more developed as a scientist because of it, and whatever happens you should be proud of what you’ve done.

In the end, this princess and general could have chosen to slaughter the villainous Thesis, but instead she adopted it and made it her friend. Now it serves her as a memory charm and library guardian for all the work that came before, and acts as a reminder for her to be kind to all those that are following in her footsteps.

All opinions in this blog are my own

If you would like more tips and advice linked to your PhD journey then the first every Girlymicrobiologist book is here to help!

This book goes beyond the typical academic handbook, acknowledging the unique challenges and triumphs faced by PhD students and offering relatable, real-world advice to help you:

- Master the art of effective research and time management to stay organized and on track.

- Build a supportive network of peers, mentors, and supervisors to overcome challenges and foster collaboration.

- Maintain a healthy work-life balance by prioritizing self-care and avoiding burnout.

- Embrace the unexpected and view setbacks as opportunities for growth and innovation.

- Navigate the complexities of academia with confidence and build a strong professional network

This book starts at the very beginning, with why you might want to do a PhD, how you might decide what route to PhD is right for you, and what a successful application might look like.

It then takes you through your PhD journey, year by year, with tips about how to approach and succeed during significant moments, such as attending your first conference, or writing your first academic paper.

Finally, you will discover what other skills you need to develop during your PhD to give you the best route to success after your viva. All of this supported by links to activities on The Girlymicrobiologist blog, to help you with practical exercises in order to apply what you have learned.

Take a look on Amazon to find out more

[…] PhD Top Tips: Write a thesis they said, but not like this they said Surviving Your Viva: My top 10 tips for oral exams I Passed my PhD 6 Years Ago This Week: What Tips do I Have for Those Who Are in the Process? […]

LikeLike

This is a fantastic and insightful post, Elaine! Your story about your PhD journey is both relatable and humorous, and the lessons you’ve shared are invaluable for anyone embarking on their own thesis writing adventure.

I particularly appreciate your emphasis on finding a critical friend and taking advice with a grain of salt. Having a trustworthy sounding board can make a world of difference in clarifying your ideas and catching blind spots. Additionally, navigating the plethora of advice offered can be overwhelming, so reminding readers to be selective and discerning is crucial.

While you mentioned self-editing, I’d also recommend exploring professional academic editing services like PhD Writers or Academic Writing Help. These services can provide invaluable assistance with grammar, clarity, and overall structure, especially during the final stages of the writing process.

This is a fantastic and insightful post, Elaine! Your story about your PhD journey is both relatable and humorous, and the lessons you’ve shared are invaluable for anyone embarking on their own thesis writing adventure.

I particularly appreciate your emphasis on finding a critical friend and taking advice with a grain of salt. Having a trustworthy sounding board can make a world of difference in clarifying your ideas and catching blind spots. Additionally, navigating the plethora of advice offered can be overwhelming, so reminding readers to be selective and discerning is crucial.

While you mentioned self-editing, I’d also recommend exploring professional academic editing services like PhD Writers or Academic Writing Help. These services can provide invaluable assistance with grammar, clarity, and overall structure, especially during the final stages of the writing process.

Thank you for sharing your wisdom and experiences! You’ve undoubtedly empowered countless readers to approach their thesis with confidence and clarity.

LikeLike