With the news of the Oscar nominations for Wicked Part 1 coming out, I thought it was finally time to dust off this post that has been languishing in draft for over a year. I guess it will surprise none of you dear readers, that I am something of a musicals fan and Wicked is one of my favourites. I saw it for the first time on honeymoon in New York with Mr Girlymicro and knew very little about it going in. Whilst watching it, the song Popular rapidly became one of mine and Mr Girlymicro’s favourite tunes (alongside What Is This Feeling?).

The words have always triggered something in me in terms of thinking about leadership, especially the line ‘It’s not about aptitude, it’s the way you’re viewed’. With everything going on in the world right now, it feels like a really important concept to explore. Is leadership all just really all about being popular? And what does that actually mean?

When I see depressing creatures

With unprepossessing features

I remind them on their own behalf

To think of

Celebrated heads of state

Or specially great communicators!

Did they have brains or knowledge?

Don’t make me laugh!

They were popular!

Please!

It’s all about popular

It’s not about aptitude

It’s the way you’re viewed

So it’s very shrewd to be

Very very popular

Like me!

What’s makes someone popular?

I’d like to start this by saying that I don’t really think I would know what makes someone popular from first principles. If I was in a 90s school based movie, like Mean Girls or Clueless, I would definitely be the girl who hides out in the library rather than being an IT girl or one of the popular kids. So, I’m probably not coming from a position of expertise on this one. I have however put those library skills to use and come up with this from those with greater expertise:

This popularity doesn’t just impact how we interact with others, it also impacts how we are treated, opportunities that we are offered, and helps reduce negative emotions linked to social rejection. This may seem self evident but it is also backed up by research with one study defining popularity as ‘generally accepted by one’s peers’.

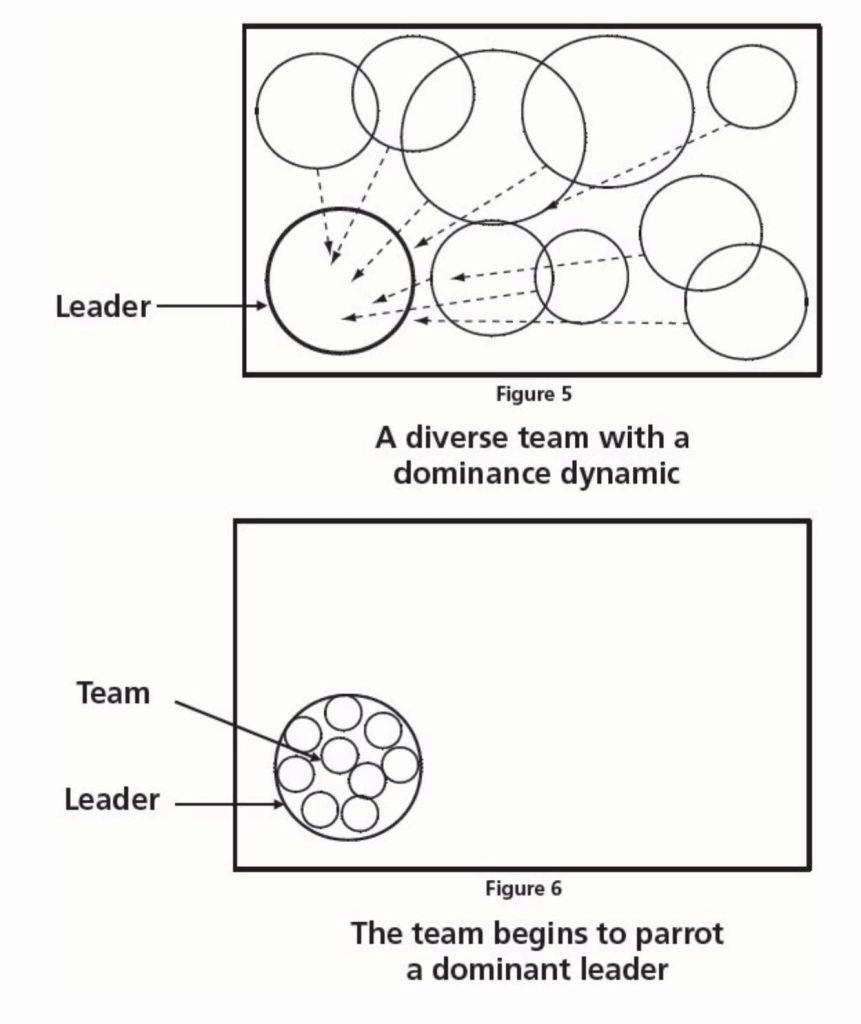

How we are perceived by others can, therefore, definitely impact on our working lives and likability, or popularity. Whilst how we are liked one on one is referred to as inter-personality, popularity is determined at the group, rather than the individual level, and is related to a person’s ability to make others feel valued, included, and happy on a more general level. The question is………is all popularity therefore about making others happy, and is leadership therefore all about attempting to make the most people happy in the widest possible way? Does getting ahead professionally mean that you need to be part of the ‘in crowd’ in order to succeed.

Is it all about people pleasing?

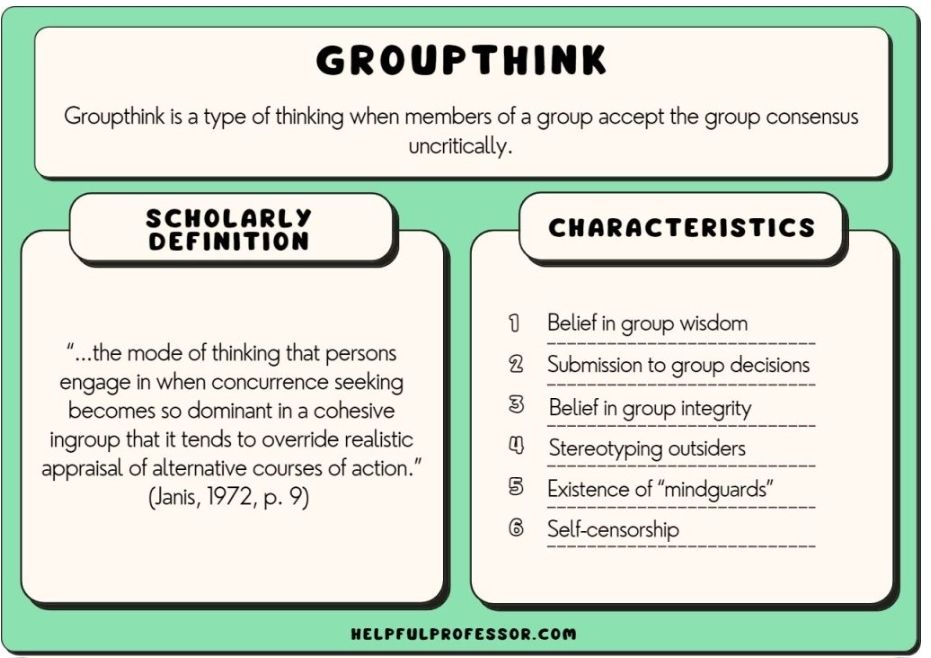

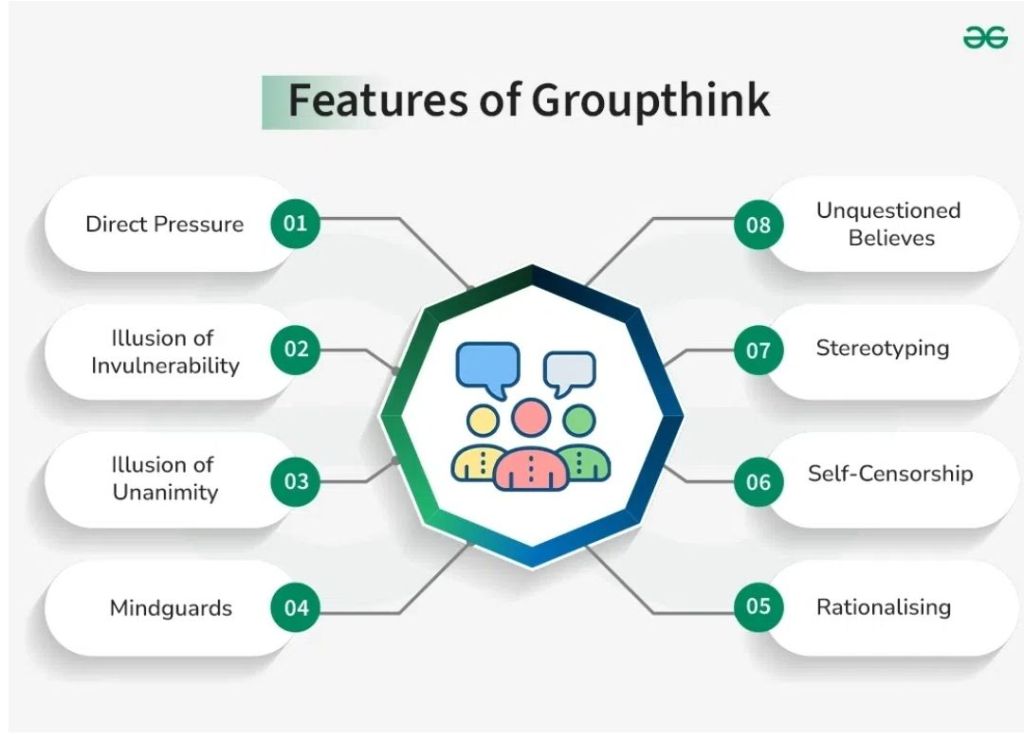

If you’ve seen Wicked, there is a great scene where The Wizard talks about how he wants to be seen. A lot of the plot across the entire musical is about superficial appearances rather than the ‘truth’. A lot of sub-par decision making within the plot is hidden behind the mask of popularity, and poor leadership is permitted because of the wide spread popularity of those making the choices.

I’ve written previously about the challenges of being a people pleaser and how it is impossible to please everyone. One of the challenges, in terms of leadership, is that if popularity is considered to be the way forward, in terms of being a good leader, you will be forced to chase good opinion rather than focusing on strategic or other vision. It also inevitably leads to your leadership being less and less authentic as you try to follow, not your central ethos, but a diluted version based on the perceived views of others.

What are the advantages of being civil?

So am I saying that it is not necessary to be nice? Just being ‘nice’ is often considered to actually be a disadvantage within work place settings, it is often good for making friends in a 1:1 setting, but as I’ve said popularity is determined on the group rather than the individual level. Within this context being nice or perceived as ‘warm’ can actually have a negative impact on careers, as warmth is often considered to be inversely associated with competence i.e. you can’t be nice and good at your job. According to Porath (2015), being seen as considerate may actually be hazardous to your self-esteem, goal achievement, influence, career, and income. So being nice alone is not enough. What does allow the switch from nice to being popular?

According to the same paper by Porath, it is about not being considered nice, but is actually linked to respect, and in this context civility, which comprises of both warmth and perceived competence:

“Civility is unique–—it leads people to evaluate you as both warm and competent. Typically, people tend to infer that a strength in one implies a weakness of the other. Many people are seen as competent but cold: He’s really smart . . . but employees will hate working for him. Or as warm but incompetent: She’s friendly . . . but probably is not smart. Being respectful ushers in admiration–—you make another person

feel valued and cared for (warm), but also signal that you are capable (competent) to assist them in the future.”

Civility, in this professional context, demonstrates benefits that being nice alone does not, especially in the context of leadership, where those who reported feeling respected by their leader reported 89% greater enjoyment in their work and 92% more focus. So maybe less about pop…u…lar and more about civ…..ili….ty? Or maybe they are one and the same thing?

Being able to be civil is itself a privilege

I do have quite a significant word of warning linked to this linking however and that is, is the ability to be civil linked to privilege? If being considered civil, and gaining the associated advantages, linked to not having to fight or voice unpopular opinions? Anything that requires warmth as part of the algorithm risks benefiting those who are in a position where they can court popular support, rather than feeling like they need to make a stand. Having the energy and resources to be able to invest in being seen as civil is in-itself linked to privilege. If you are working part time or under resourced, you are unlikely to have the time resource to invest in some of the relationship building needed to be identified as both warm and competent. There are also people who believe that they cannot invest because of the risks to their careers in coming off as warm without the associated benefits of being seen as competent. The costs in terms of income or self esteem are not ones that everyone can risk in case it goes wrong.

Is civility just another way of benefiting those already in positions of seniority?

Is it therefore that civility, and it’s associated popularity, are just another route that benefits those that are already in a position of privilege. Is popularity linked to status? Traditionally status is based on attention, power, influence, and visibility, rather than acceptance from peers, and so popularity may be more significant in informal vs formal leadership settings. This isn’t saying that senior leaders shouldn’t be civil, and that they shouldn’t come across as warm. It does mean that they are probably at lesser risk from the disadvantages and risks once they are in a formal leadership position, where they are able to draw upon different markers of power and visibility to gain influence. This can give the false impression that you need to be popular in order to be a senior leader, whereas the reality may be that you can afford to be popular as a senior leader as you are less at risk of any of the negative consequences of you only being viewed as part of the equation.

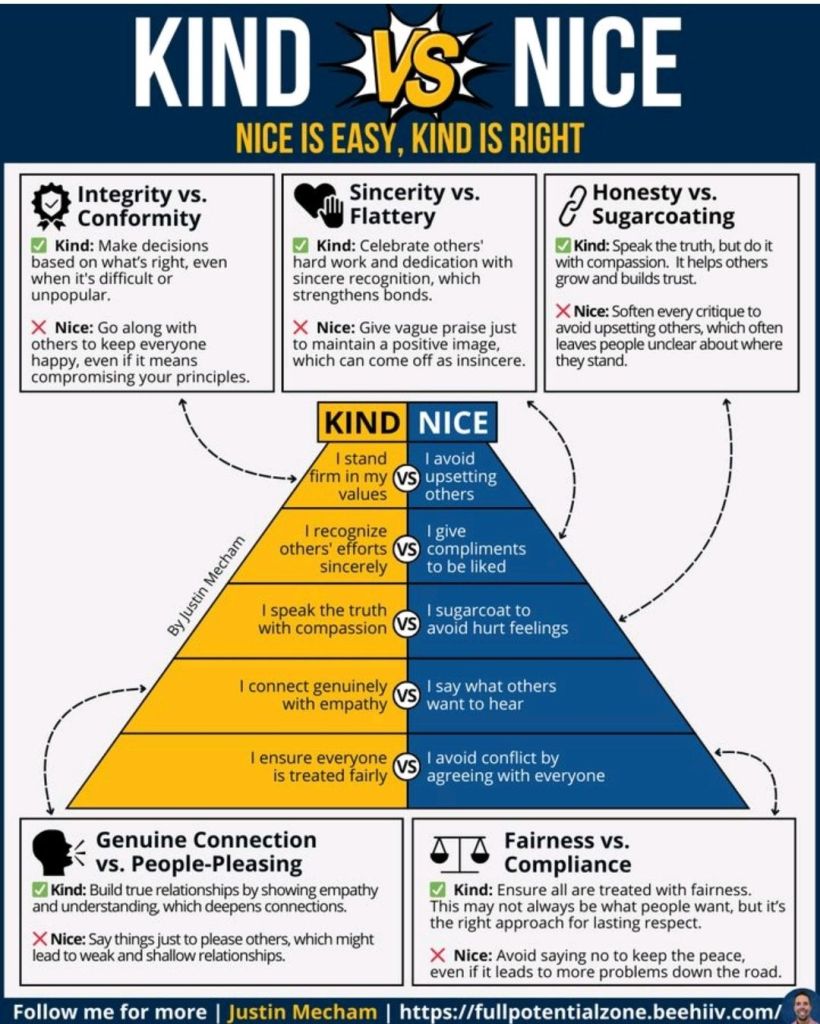

What is the difference between being nice and being kind?

So, I’ve talked about being nice as not always a risk free move in terms of career progression, but what about kindness? I’m a massive advocate of kindness, but sometimes I wonder if people have the same understanding of the term as I do or whether they use it as a proxy marker for other things. For instance, we often talk about kindness and niceness as if they are interchangeable, but I’ve been wondering if the difference between the 2 is where the perception of warmth vs civility (combined warmth plus competence) actually sits.

I have certainly met people who believe that being kind and supportive means always being in agreement or always saying yes, whereas I believe that this is more acting from a position of people pleasing and being nice. In contrast I believe that sometimes the kindest thing that you can do is to say no, either because you’re not in a position to deliver what they want or that saying yes would put the other person in a challenging position. Nice can often feel right in the moment, whereas kind considers the wider, and sometimes longer term, implications.

How do we manage kindness in a way that is authentic?

Being kind can be challenging as it is not always about taking the easy route, sometimes it’s about making hard choices in order to help yourself, others or the organisation, to be the best version of itself. It can challenge some of the behaviours linked to people pleasing in order to move towards authenticity in terms of interactions and leadership. For me, kindness is very much about doing the right thing instead of the easy thing, but to really deliver on your values, you need to invest the time to understand what those values are first. What do we stand for? What three words would we assign to our core descriptors of self? Knowing what your core values are enables you to have a self check benchmark to help identify when we are being nice over kind.

Where does social capital fit in here?

Obviously, civility and kindness are not the only factors that come into play in the ‘popular’ discussion. There are all kinds of other forms of social capital that can impact on how successful we are at network building, influencing and leadership. Especially in the world of science and healthcare, expertise comes into play quite significantly, and access to funding can never be under estimated, in terms of providing leverage and empowerment.

It is always worth being aware of, and investing in, all of these different strands for long term success. Having said that, all of these also require you to have the capacity to invest. As someone who can’t have children, and therefore have greater freedom to balance my work and home life, I’m aware that I probably wouldn’t have been able to build a clinical academic career if my life had been different. If I’d had to leave on time for school pick up or had to be lead carer on the weekends, I wouldn’t have been able to publish the papers or apply for the grants required. There is inbuilt privilege in my being able to prioritise my career at times. This blog requires hours every week. Hours that I enjoy investing and which I reap the benefits of in terms of networks and connections. These are things that I wouldn’t be able to do if I needed to pick up a second job or was caring for a parent. When we ask people to have these additional pieces of capital to progress, we need to be aware that we are putting barriers in place so that not everyone can make the most opportunities. We need to make the most of the tools we have available to us, but as leaders, we also need to understand how to support people to access opportunities in a way that doesn’t disadvantage them in relation to others.

Let’s not forget that leadership is hard

I think that one of the things that it is often easy to forget is that leadership is hard, in some ways, if it’s easy you probably aren’t doing it right or stretching yourself enough. Part of leadership is making the unpopular and challenging decisions, and sometimes there are no win wins. Being popular, being considered empathetic is always a nice thing but it is not the only thing that makes your leadership successful. So is it, in the end, actually all about popular? If you were to ask me it is instead all about authenticity. The key thing, from my perspective, is to let people know who you are, connect with people as much as possible and share/co-create the vision. Then they can make informed decisions about whether to get on board the Girlymicro train or not! On this one, I may be with Elphaba.

All opinions in this blog are my own