This month I’ve been honouring of World DNA day 2025 by publishing a number of posts linked to what DNA is, how we look for it, and what it means to send it away.

Today I’m talking about Upgrade by Blake Crouch. In the story explored in this world, DNA based technology, although very obviously rooted in present day science, has evolved and so has the impact and access to this technology for both individuals and society. In this post I thought it might be interesting to explore ow much of this book is science, and how much of it is fiction? Before I get onto that however, here’s a reminder of the other posts that have been available in the DNA blog series:

One of the reasons I picked Upgrade for the final book review is that I thought it would be interesting, after discussing the current usage of DNA for testing and therapies in previous posts, to explore a book that covers a slightly further future, based in 2060, and what impact the use of DNA technologies could have on humanity in the future.

‘You are the next step in human evolution . . .’

What if you were capable of more?

Your concentration was better, you could multitask quicker, read faster, memorize more, sleep deeper.

For Logan Ramsay, it’s happening. He’s beginning to see the world around him, even those he loves the most, in whole new ways.

He knows that it’s not natural, that his genes have been hacked. He has been targeted for an upgrade.

Logan’s family legacy is one he has been trying to escape for decades and it has left him vulnerable to attack. But with a terrifying plan in place to replicate his upgrade throughout the world’s population, he may be the only person capable of stopping what has already been set in motion.

To win this war against humanity Logan will now have to become something other than himself . . .

In this world, DNA based technology, although very obviously rooted in present day science, has evolved and so has the impact and access to this technology for both individuals and society. It raises some interesting questions about what it means to be human. In this post I thought I would explore some of the science that is included, and what questions the use of this science brings into play.

Are visions of a world where DNA controls our lives unique?

Before I get into the science of the book however, I wanted to flag that visions of a world where the use of DNA testing, evaluation or modification, are not new. GATTACA (did you see what they did there……they are all DNA bases) have been around since the 90’s, when the technology we use clinically now was only in its infancy. Fear of how science could be used in the future is a pretty constant feature of this type of creative content, as it provides a safe way to explore these fears and ethical challenges. I suppose what I’m saying is that just because something is included in these kinds of visioning pieces does not make it bad, wrong or scary. It just means that we also need to think and reflect on what checks and balances are included as part of their introduction in order to make sure the world we create and influence based upon them is the one that we are aiming for, and we have taken steps that include the law of unexpected consequences rather than ignoring it. DNA editing is an amazing, technically complex and powerful tool that has the potential to be positively life changing, so please keep that in mind when you read the rest of this post.

The world of upgrade

In the world of Upgrade the impacts of climate change have really been felt. Entire cities have been flooded as the seas rise and access to food has become a real issue for vast portions of the worlds population. Logan, our protagonist is the son of a genius, a woman changing the face of science. Being the child of a world famous geneticist makes Logan feel the reality of being a normal person surrounding by an extraordinary vision.

I had extraordinary dreams but had been gifted only an ordinary mind

Sadly, as is often the case in these tales, his mothers (Miriam Ramsay) drive for change comes with a fair amount of hubris. In an attempt to address the food shortages Miriam, with Logan supporting as a junior scientist, develops a new gene editing tool called Scythe in an attempt to genetically enhance rice crops. The process goes wrong, and results in The Great Starvation that leads to the deaths of 200 million people.

As a result of the mass deaths, genetic manipulation using Scythe or related tools originating from CRISPR, are outlawed and their use results in a mandatory 30 year minimum jail term. Thus making the field of genetics either outlawed or suspect, and to the birth of the Gene Protection Agency, a police force which aims to track down those undertaking illegal manipulations or research.

Logan ends up going to prison for his work with his mother’s research, and his mother commits suicide. After serving his time Logan is released and joins the very agency that has been set up to prevent a repeat of the genetic manipulation that changed the world. At the start of the book Logan is investigating a scene where an explosion happens, his body is hit by shards of ice, and his life changes again…..forever.

My mother had tried to edit a few rice paddies and ended up killing two hundred million people. What havoc could she wreak—intentionally or through unintended consequences—by attempting to change something as fundamental as how Homo sapiens think?

So, what is gene editing?

I’ve already mentioned CRISPR but I’ve not described what it or gene editing actually are. Gene editing as defined by the World Health Organisation is:

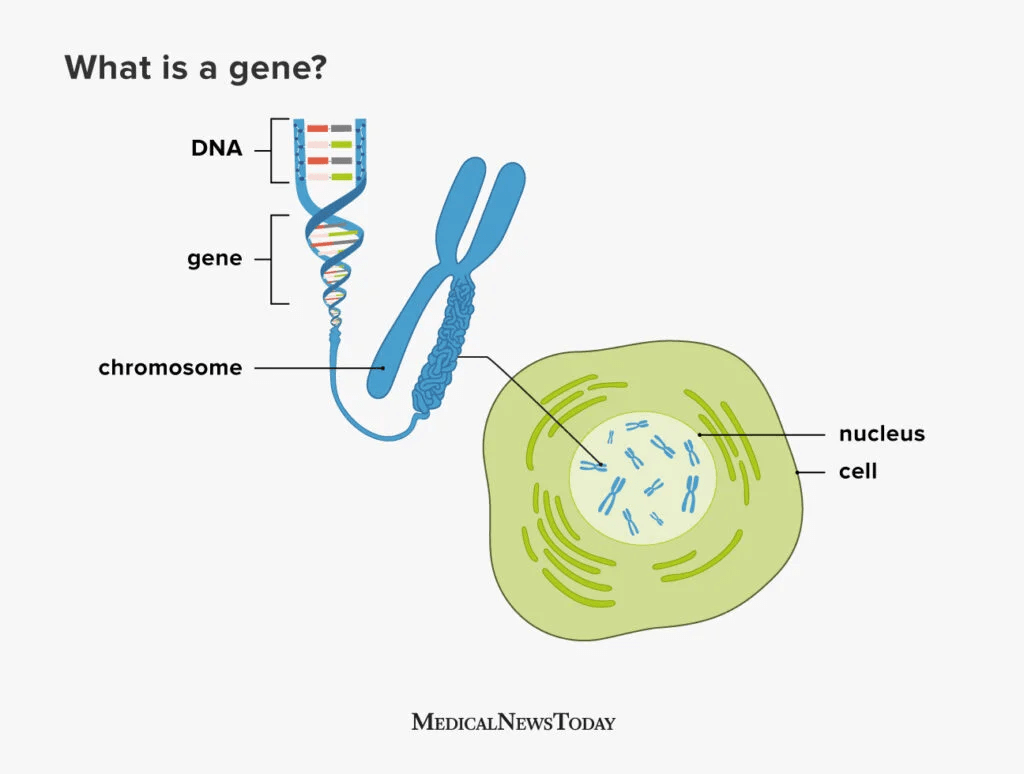

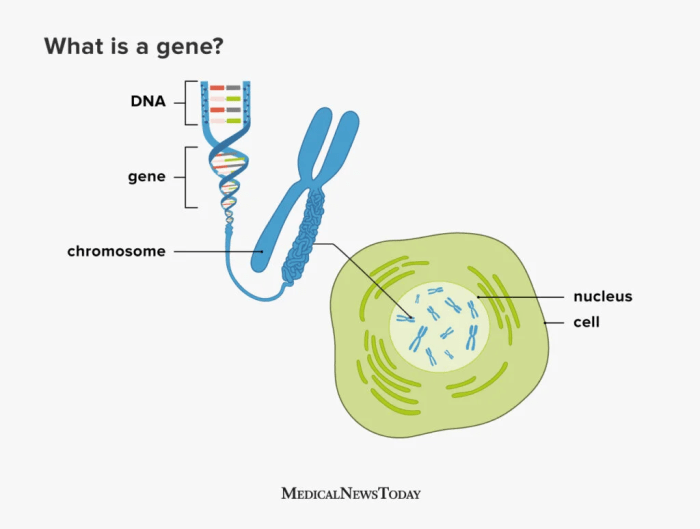

A method for making specific changes to the DNA of a cell or organism. It can be used to add, remove or alter DNA in the genome. Human genome editing technologies can be used on somatic cells (non-heritable), germline cells (not for reproduction) and germline cells (for reproduction).

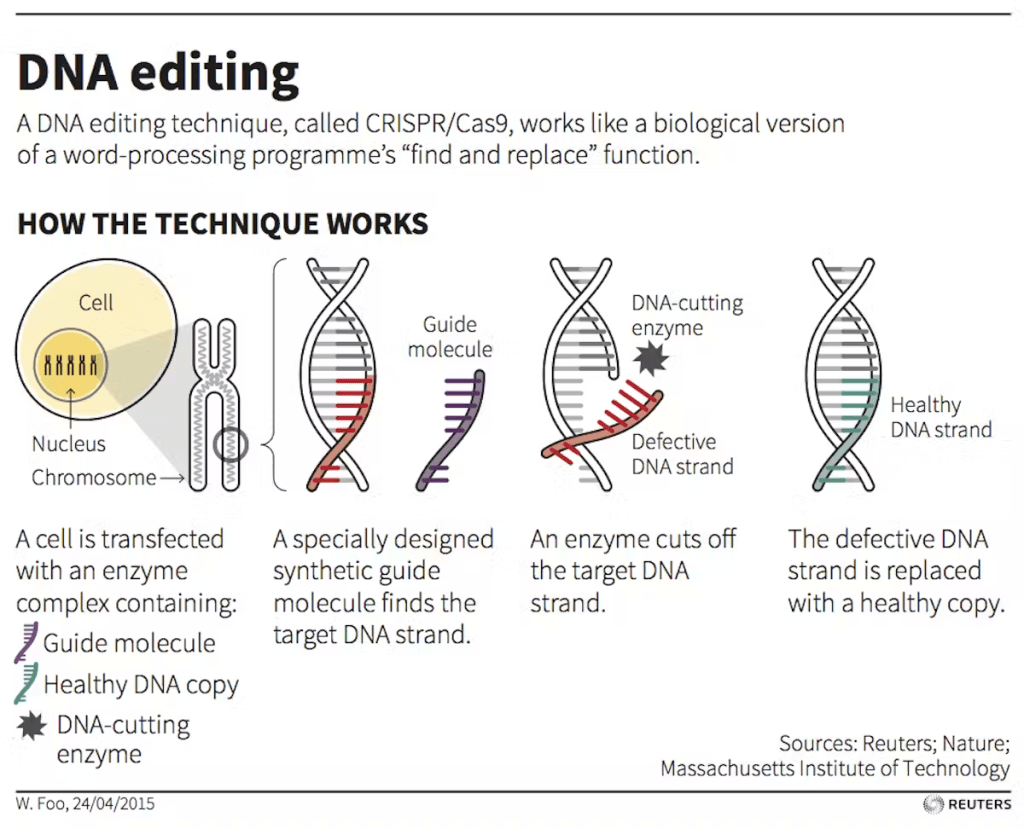

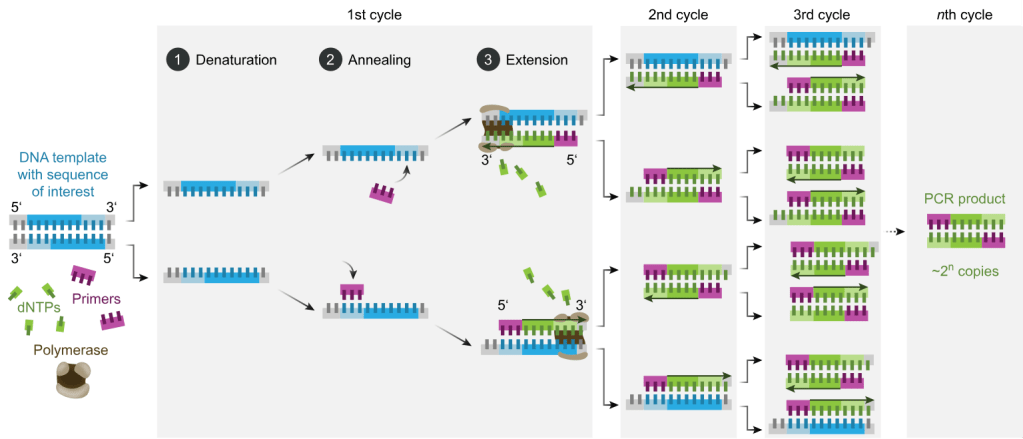

Before I go further I should probably talk about how CRISPR works and what it is used for. Tools like CRISPR/Cas9 are tools for gene editing, and are the present day origins behind the futuristic tools present in Upgrade. Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2020 for the development of CRISPR, commonly referred to as genetic scissors.

CRISPR allows you to design a targeted way of manipulating a gene section that you are interested in, and in some cases then replace it with an alternative gene section, which enables the gene to function in a different way. Being able to target and replace, or inactivate genes, in this way opens up a whole new world of possibilities, from health to industrial applications. There are three main approaches to gene manipulation:

- Replacing a disease-causing gene with a healthy copy of the gene

- Inactivating a disease-causing gene that is not functioning properly

- Introducing a new or modified gene into the body to help treat a disease

Now, wearing my geek credentials on my sleeve, I wanted to share with you a music video that describes how CRISPR works. It’s set to the music of ‘Mr Sandman, bring me a dream’ and is retitled ‘CRISPR/Cas9 bring me a gene’. I love this as it I think it describes the history of the process really well. I will tell you now though, that when I made Mr Girlymicro watch this for the 5th time he could not get out the room fast enough, so this may just be a me thing.

Where is the science rooted in the present?

Having talked about the fact that gene editing isn’t the work of science fiction, I thought it would be useful to talk about how and where it is actually being used right now.

According to the Federal Drug Administration there are a variety of types of gene therapy products, i.e. products that manipulate genes, currently available:

- Plasmid DNA: Circular DNA molecules can be genetically engineered to carry therapeutic genes into human cells.

- Viral vectors: Viruses have a natural ability to deliver genetic material into cells, and therefore some gene therapy products are derived from viruses. Once viruses have been modified to remove their ability to cause infectious disease, these modified viruses can be used as vectors (vehicles) to carry therapeutic genes into human cells.

- Bacterial vectors: Bacteria can be modified to prevent them from causing infectious disease and then used as vectors (vehicles) to carry therapeutic genes into human tissues.

- Human gene editing technology: The goals of gene editing are to disrupt harmful genes or to repair mutated genes.

- Patient-derived cellular gene therapy products: Cells are removed from the patient, genetically modified (often using a viral vector) and then returned to the patient.

There are a number of ways that gene therapy products are already being used for the clinical management of patients, including for patients with conditions such as HIV and sickle-cell disease. One big change that has occured during my clinical career is the use of CAR-T cell therapy for tackling some types of cancer. CAR-T cell therapy is a type of immunotherapy where a patients own T cells (type of white blood cell) are taken from a patient who has cancer, and the cells are then modified in order to better recognise and attack cancer cells within the patients body when they are then given back. So gene editing is already saving lives and in every day use, even if its roll out is currently limited.

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cx2yg9yny0ko

Are these changes transmissible?

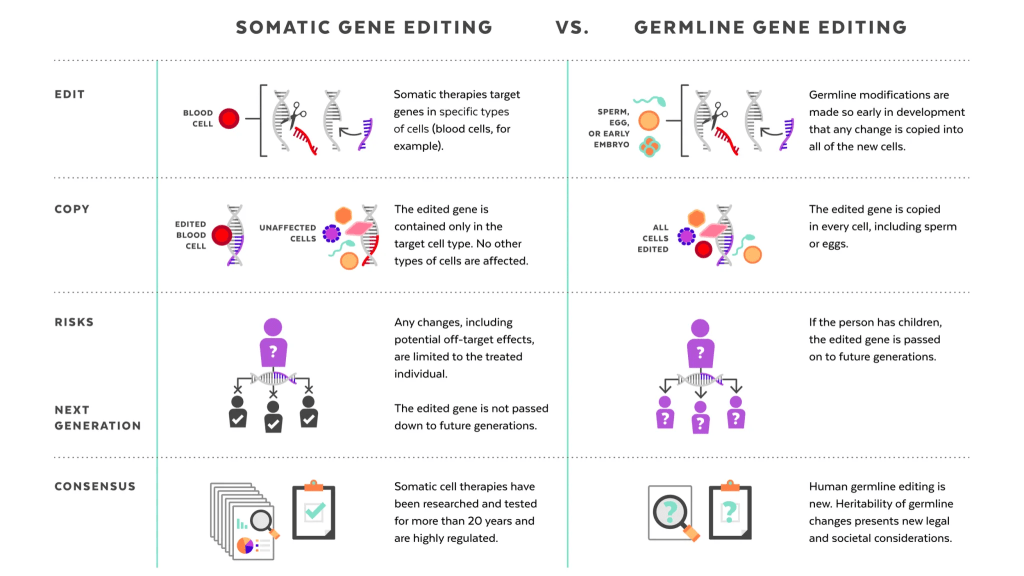

Having established that gene editing is very much the next frontier for expansion in healthcare, it’s probably important to consider how stable these changes will be within the wider the gene pool. It’s worth noting that the human genome editing techniques that are being introduced in healthcare are linked to somatic cells, where changes would be non-heritable, rather than within germline cells, which are involved in reproduction, where any changes would be inherited by future generations. Most of the changes that are currently being targeted for gene therapy would not therefore cause the changes to be established within the gene pool. There is a question about whether the target genes, even for somatic changes, may become more established as some of those carrying them may not have previously survived to reproductive age, but to be honest this feels like the impact will be minimal and a price worth paying as a society for improving both quality and length of life in those impacted. Changing future generations of children is however a whole different ball game.

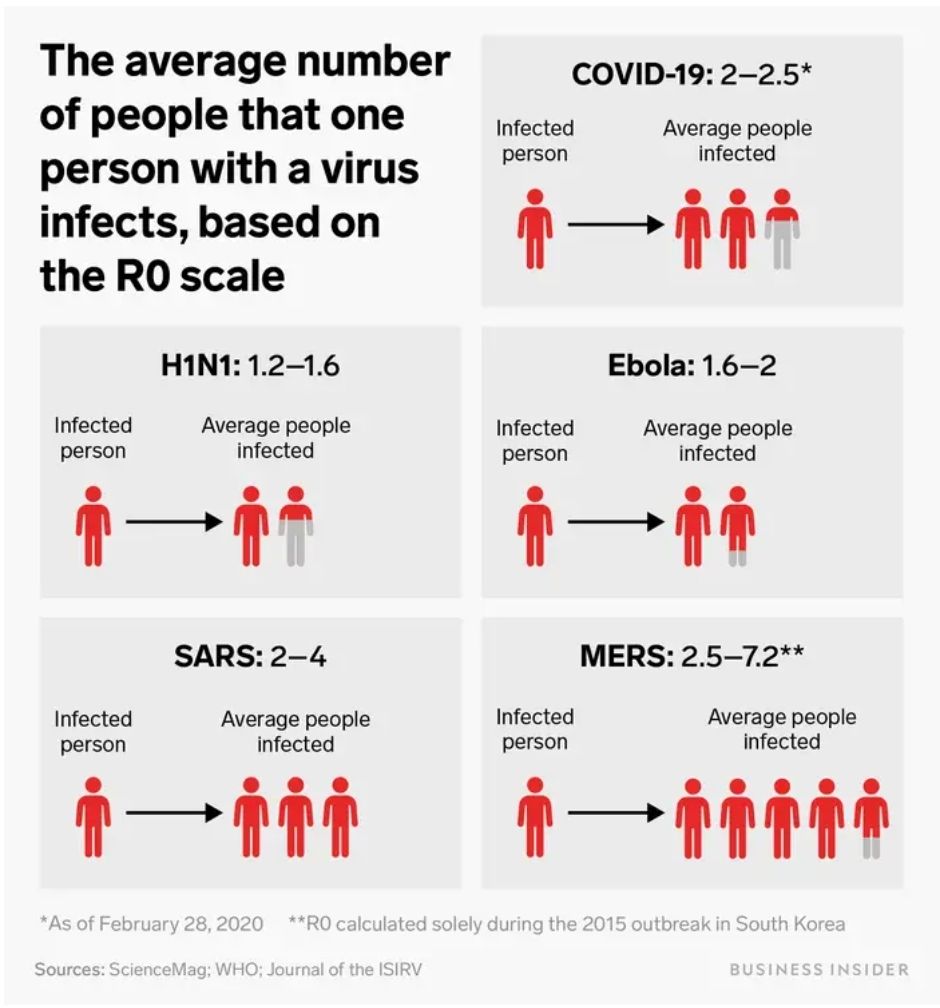

The technology discussed within Upgrade has moved on somewhat from CRISPR. It retains some features of current technology however, as the delivery of Scythe is via viral vector. The interesting thing about this form of delivery is that, in the world of Upgrade, the viruses have been modified and use their standard invasion routes to deliver the genetic material into cells, but, unlike the way that this is being undertaken as part of gene therapy in current healthcare, the viruses do not appear to have been fully modified to remove their ability to cause infectious disease. Some of the plot, therefore, is driven by the fact that it is possible to undertake wide spread indiscriminate gene editing within the human population. The modified viral cells retain their transmissibility alongside their gene editing functionality, and so a gene manipulation can spread in a similar way to any respiratory viral infection. The R0 within Upgrade is 8, which means that every person infected will infect, on average, 8 other people, which means the potential for spread within the population is massive. (If you want to know more about what an R0 is, I’ve covered it in a previous post here). It is not clear to me whether the gene targets within Upgrade are targeting just somatic changes, or a combination of somatic and germ line, but when you can spread so widely so quickly that is probably not the main consideration.

What questions does Upgrade raise?

Within the world of Upgrade, the gene editing doesn’t just target a single gene, but a whole suite of different genes for large scale changed. The problem with using gene manipulation that changes multiple gene targets, that are non-personalised to the condition/individual, and are highly transmissible, is that it is highly likely that the changes won’t work for everyone’s genome. There are going to be side effects or potentially significant impacts. Within Upgrade these are seen through errors that then occur in the brain due to protein mis-folding, very similar to how prion diseases work. The change in some people is catastrophic and there is no intervention available to reverse it. Using indiscriminate gene manipulation has the power to create mass disruption and change societies. It is this power for change that is the jeopardy that drives the novel. Is the cost worth the outcome, and who gets to decide? How much collateral damage would we be prepared to accept, even if the wider benefit to society is a positive one?

October 2022

In book: Viral, Parasitic, Bacterial, and Fungal Infections Antimicrobial, Host Defense, and Therapeutic Strategies (pp.651-662) Edition:1 Chapter: 53 Publisher: Elsevier: Academic Press

What does it mean to be human?

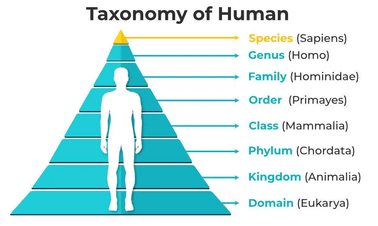

As part of this risk/benefit consideration, Upgrade asks a lot of questions of the reader, the main one of which, for me, is what does it actually mean to be human?

There is a genetic definition of what it means to be human, but the gene modifications within humans causes our protagonist Logan to ask some very valid questions about what it actually means to be human. Is it just about genetics? How much can we change not only our genes, but our outlook/perceptions, as people and still remain human?

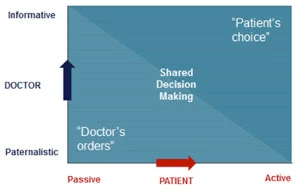

The ‘upgrades’ received cause different characters in the book to judge humanity in general, and other human beings, in very different ways. Do genetic changes make you superior? Does being intellectually smarter permit you to make decisions for others for their benefit, as determined by the smarter individual? In many ways this brought to mind, for me, the old approach to clinical decision making, which was very paternalistic and the role of the person/people impacted was highly passive. I’d like to think we are now moving towards a much more patient focus decision making process, but this book made me think about what would happen if this model was used, not just for one to one interactions, but for the future of humanity.

The question about decision making is an interesting one however. There is plenty of data that demonstrates improved decision making in small groups, and if time is of the essence how would you engage with enough people for a decision to be valid? Especially a global decision? How many people would you need to interact with for a choice about changing the DNA of your species to be valid? How would you manage a lack of consensus? Would you let the world burn whilst the choice was being made, or would you accept that at some point someone would need to step in and lead the way forward? It’s the uncomfortable space between ethics and pragmatism, and definitely not something that is easy to answer, even conceptually.

Is intelligence the problem?

As discussed above, a lot of the plot driven by the counter to our protagonist in Upgrade, is based on the concept that if humans were smarter they would make better decisions. Therefore, by improving how people think and removing some of the emotional component the human race would be improved and therefore ‘saved’. This is especially important in the world of Upgrade, as because of the damage that is being done linked to climate change and other damage caused by humanity, the clock is ticking and Logan is very aware in his upgraded state that there is only 100 years left to save mankind.

The problem, as it plays out to me, is that it is very much not about intellect however, it’s about the ability of individual humans to care enough for others. For one person to make decisions that costs them rather than benefits them for the sake of someone that they do not know well if at all. This is especially true for problems that are going to impact future generations, like climate change, where the people most impacted have yet to be born. By the time we ‘meet’ those who will be most affected it will be too late to save them. Even for a present day context it raises questions, we all think of ourselves as having empathy and caring for others, so why does that not play out and allow us to care for the migrants that are dying trying to join us and share in our safety? Why is our compassion so limited?

One of the reasons for this has nothing to do with intellect, and would in no way be altered no matter how smart we become. It’s based on a theory known as the Dunbar number, which predicts that we can only empathise with a maximum number of 150 people, the number of people that would likely to have been the maximum size of our primate tribe. More than this, we can only truly care, to the point we may want to sacrifice, about a much smaller number of people. The book therefore postulates that we aren’t held back due to a lack of intelligence or innovation, we’re held back by a lack of compassion and the ability to truly care about people we don’t know and will never meet. If we are to change anything about ourselves in order to save mankind therefore, it’s not intellect we need more of, we need to find a way to increase our capacity for compassion and therefore change our Dunbar number, to adapt for the world we now find ourselves in. So maybe the answer to the problem is to become more ‘human’ rather than less.

Where do all of these questions leave today’s gene editing technology?

Gene editing technologies are making massive strides, saving lives, and positively helping people who have serious health conditions.

Somatic gene editing is well established, and has been developed over the last 20 years so that regulation is in place, and it being more and more routine rolled out in countries that have access to advanced scientific technologies. The problem is just that however, these interventions are technologically challenging and incredibly expensive, and therefore not universally available. This means that they also do not necessarily take into account the diversity of the human genetic population or the lived experience within different cultural communities. Regulation is also not present universally, with some people forced to access these therapies through the use of rogue clinics, or by undertaking medical tourism, which brings with it increased risk. There is also the potential for illegal, unregistered, unethical or unsafe research and other activities, including the offer of unproven so-called therapeutic interventions, as with any emergent technologies. Ensuring equity of access and appropriate regulation will be essential to ensure a safe global adoption of these therapies.

Germline gene editing is however in a very different place, as this would lead to the editing of DNA in a way that may be heritable across generations. There is an intense debate linked to its use as the the future generations that would be impacted would have no capacity to consent to the changes, and or risks, that are being made. There could be possible risks and consequences for offspring and for society in general, and once that genie is released it will not be possible to put it back in the bottle. Discussing what circumstances it would ever be appropriate to undertake these changes requires us all to be actively engaged in these discussions.

I hope you’ve enjoyed these series of blogs linked World DNA Day and taken some to celebrate the miraculous nature of just being you. I’ve really enjoying sharing some of the technical information, but also diving into some fictional worlds and discussing the thoughts that they provoke. With summer coming up I hope you may even pick up a copy of these great novels and dive into their worlds yourself. If you find any others in your reading adventures, return the favour and let me know. I may even include them in a future review. Happy reading.

All opinions in this blog are my own