Dr Claire Walker has been a paid up member of the Dream Team since 2013, token immunologist and occasional defector from the Immunology Mafia. Registered Clinical Scientist in Immunology with a background in genetics (PhD), microbiology and immunology (MSc), biological sciences (mBiolSci), education (PgCert) and indecisiveness (everything else). Now a Senior Lecturer in Immunology at University of Lincoln. She has previously written many great guest blogs for The Girlymicrobiologist, including one on turning criticism into a catalyst for change.

What may be less well known, even to regular readers of this blog, is that she did her PhD on finding genetic diseases, and as this ties in so well with the recent blog series I’ve been doing on DNA I thought having a guest blog from Claire might be the cherry on top of this particular ice cream sunday!

If you’ve missed any of the blog series of posts, especially if you want a refresher on how DNA works before reading about Claire’s work, I’ve included links to all the posts the below:

Having spent some time covering what is however, I thought I would follow up with a couple of book reviews that focus on how the world of DNA, DNA editing and DNA interpretation could change the lives of everyone involved.

The first of these was The One by John Marrs:

The second was for a book called Upgrade by Blake Crouch:

Blog By Dr Claire Walker

When I was 26 I finished my Clinical Scientist training and was offered a full-time position at the hospital I trained in, with a good pay increase and a view to becoming a laboratory manager in the next few years. It was a great gig with a lovely team, good earning potential and support to further my clinical training. Unfortunately for them, I had just completed a secondment to a famous children’s hospital and had my mind absolutely blown. I had seen how immunology was being influenced by the study of human genetics, at the forefront of the field with cutting edge techniques which seemed, frankly, indistinguishable from magic. Suddenly, working in adult rheumatology and learning how to manage NHS laboratory budgets just didn’t seem so interesting anymore. So I turned down the job, went home, looked my husband in the eye, and said the words he’d been quietly dreading ever since I’d first jumped from environmental microbiology to human immunology: ‘I think I want to retrain… again.’

I applied for a PhD in genetics and immunology at University College London Institute of Child Health. Specifically, I focused on children with rare syndromes that didn’t have a clear diagnosis often called “syndromes without a name.” These kids and their families had often been on a long and frustrating diagnostic journey, seeing specialist after specialist, with no real answers. That’s where exome sequencing came in. By reading the protein-coding parts of the genome — the exome — we hoped to find clues hidden deep in their DNA that could point to the cause of their symptoms. Think of it like a high-stakes game of genetic detective work. Each patient’s exome was a puzzle, and sometimes, we’d find that one variant that explained it all. Other times, we discovered new candidate genes that had never been linked to disease before. Conversely, we found that some quite well-known genetic diseases could have highly unusual presentations – what we call expanding the clinical phenotype of a condition.

Figure 1. How does next generation sequencing work? Image Credit – http://www.Biorender.com

The disease I was assigned to work on was the oh-so-easy to pronounce and explain, Haemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH). HLH is a rare but serious condition where the immune system goes into overdrive and won’t switch off. Instead of protecting the body, it causes severe inflammation and can damage organs including the liver, brain, and bone marrow. It can look like a really bad infection, but it’s actually the immune system attacking the body from within. Some cases are triggered by infections or cancer, but others are caused by inherited defects in genes like UNC13D or PRF1. The children in my student were amongst the big chunk of patients where none of the usual suspects showed up on molecular testing.

Figure 2 – Syndromes without a name logo. Image Credit – http://www.geneticalliance.org.uk

But finding a genetic change through exome sequencing was only the beginning — I still had to figure out if it actually meant anything. Not all changes in our DNA cause disease, so we looked for the presence of the mutation in healthy controls and used predictive software like PolyPhen2 to solve the first clue: what would this mutation do to the protein the gene encoded? Then came the hard part — proving it. I had to design and run experiments to test how the genetic fault affected the protein’s job in the immune system, and whether that could explain the symptoms we were seeing in the child.

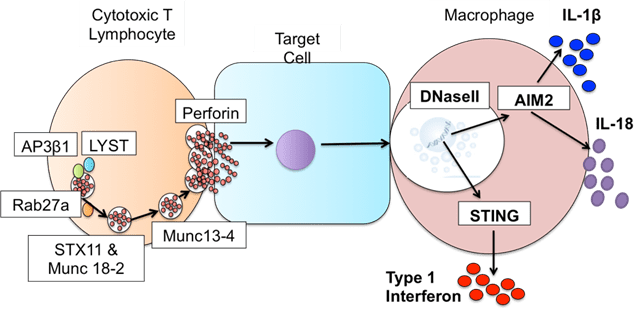

The hard work paid off, in my study we found: one case that was UNC13D protein defective HLH, but only affected the brain; one that turned out to be a totally different (and very rare) immune disorder; and one that revealed a brand-new genetic disease caused by defects in DNaseII resulting in something akin to HLH and another inflammatory condition. In all of these cases what this really gave us was the opportunity to get these kids an answer and onto treatment that could actually work for them.

Figure 3. Defects in DNaseII sit downstream of defects known to cause HLH. Image credit – Claire Walker, thesis.

For me what’s really fascinating about genetics is that what took me years of research is fast becoming a routine test – an incredible reminder of how quickly genetic technologies can evolve. What was once a complex puzzle of genetic mysteries is now providing families with the answers they’ve long needed, turning uncertainty into hope and paving the way for more personalized, effective care in the future. I think that alone was worth putting my husband through yet another ‘re-training’ episode, who knows what I’ll come up with next?

I hope this addition has given you an insight into why working to learn more about how our genes impact us is so important, but also how needed specialists like Claire are for us to do this safely and make the difference we want to make. Sometimes all patients need is an answer, a name to put to what they are going through, something that can provide a route forward even if it doesn’t provide a complete fix. Something so simple can be so difficult to achieve, but just because something is hard doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t try.

All opinion in this blog are my own