Following on from the wonderful fungal post on fungal toxins (mycotoxins) last week from Dr Sam Watkin, I wanted to follow up with a post on the latest fungi of interest from a clinical perspective, Candidozyma auris. This fungi is getting more and more coverage, as well as becoming more important in healthcare, so I thought I would take a moment to talk about what it is, what it does, how to find it, and what to do when you do.

In a pre-pandemic world, which feels like a long time ago, Professor Lena Ciric was working at a media fellowship, and as part of that work wrote an article for the BBC on Candida auris, which has subsequently been renamed to Candidozyma auris.

This article came out in 2019, so maybe C. auris is not so new but in terms of the numbers of cases we are seeing within the NHS, and the changing prevalence out in healthcare systems more widely, it is definitely more of a feature and a concern than it was back then. Reflecting this change the UKHSA guidance Candidozyma auris (formerly Candida auris): guidance for acute healthcare settings which was originally published in 2016, has been updated recently (19th March 2025). It feels timely therefore to put something out in order to raise awareness of this organism and the unique challenges it presents.

NB I can neither spell nor pronounce Candidozyma auris and so we’re sticking to C. auris from this point out.

What is it?

Yeast are a type of fungus, and Candida species are often associated with colonisation (present without causing infection or symptoms) on skin, in the mouth or within the vagina. If they grow up to high levels they can cause an infection called candidiasis, which often causes symptoms like itching or discharge. Common infections include Thrush and nappy rash. Candida albicans is one of the most common yeast infections seen within the healthcare setting, and in this kind of environment more serious infections can be seen, especially those linked to the blood stream, and occasionally serious organ infections.

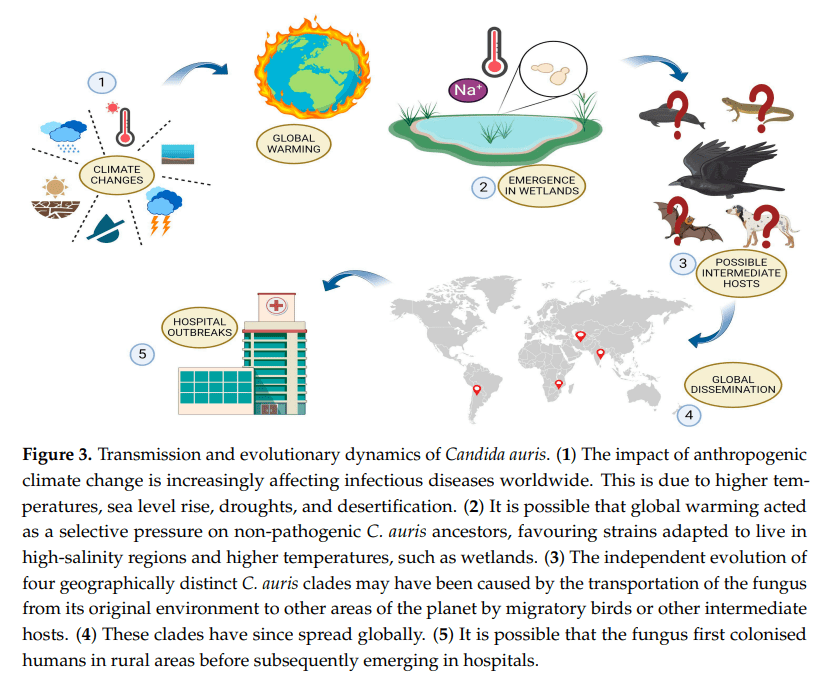

C. auris was originally believed to be a relatively new species of genus Candida, as it often behaves in a similar way to the other Candida species. The reason for the name change to Candidozyma auris, was because, although in many ways it behaves similarly to its Candida cousins, it does have some differences in the way it behaves. These include features such as intrinsic antifungal resistance and growth conditions, that make it useful to characterise in a way that acknowledges it as a novel genus in its own right.

What is the difference between C. auris and the other Candida species that you know?

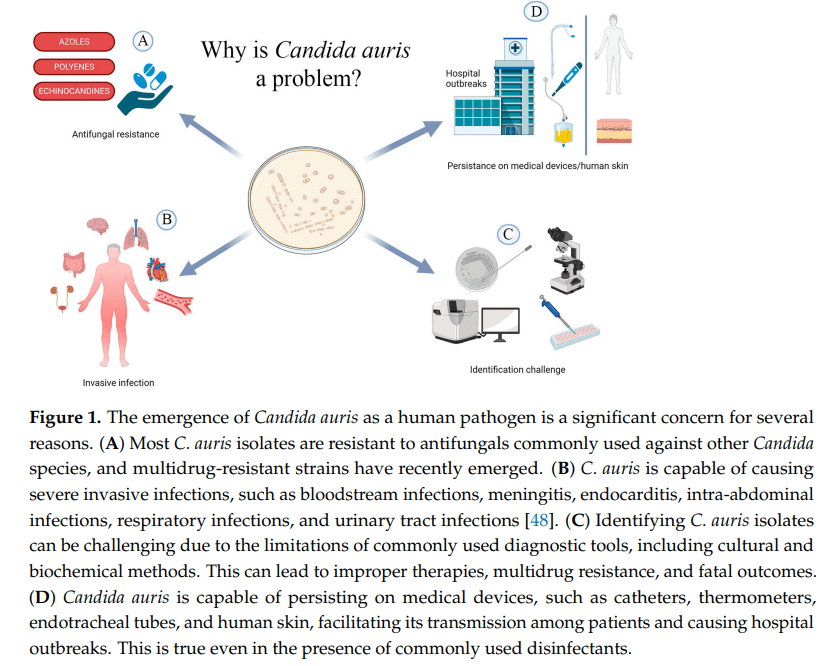

Many Candida species can cause severe infections within specific settings, however C. auris has been known to not only cause a wide variety of infections (bloodstream, intra-abdominal, bone and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) infections), but ones which lead to significant mortality rates, with an estimated rate of 30 – 72% in severe infection reported in the literature.

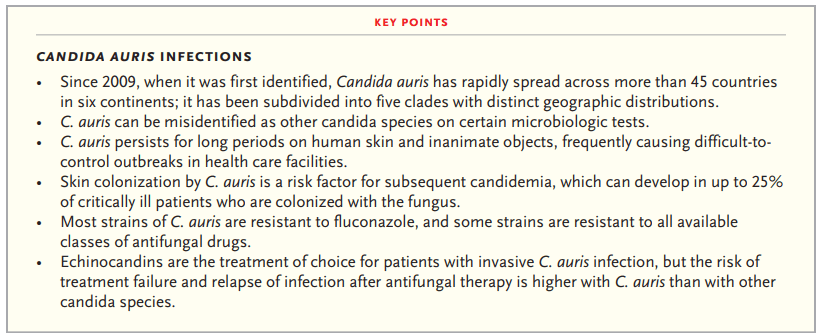

Infections can occur in any patient group, although UK outbreaks have been most frequent associated with adult settings. Augmented care settings (such as intensive care and transplant settings) are at highest risk due to the vulnerable, long stay nature of many of their patients. Management of any infection occurring is complicated by the fact that C. auris has developed resistance to many available classes of antifungals, with emergence of pan-resistant strains, which add to the mortality risk.

C. auris also appears able to both easily transmit and colonise the skin of patients, with most patients being colonised before they go on to develop any subsequent infection. These colonised patients can then contaminate their healthcare environments, and unlike other yeast species, C. auris is able to survive and represent a continued risk within the environment for prolonged periods, all of which contributes to outbreak risk.

Geographic distribution

It was first identified in the ear canal of a patient in Japan in 2009, but has since been found globally, and is now separated into six genetically distinct clades:

- Clade I = the South Asian clade, first detected in India and Pakistan

- Clade II = the East Asian clade, first detected in Japan

- Clade III = the South African clade, first detected in South Africa

- Clade IV = the South American clade, first detected in Venezuela

- Clade V = Iran (recent)

- Clade VI = Singapore (recent)

Within the UK from January 2013 – December 2024, 637 C. auris isolates were reported through laboratory surveillance in England, with 59 (9.3%) isolated from blood culture specimens. It should be noted that not all labs report, and for some time many labs could not accurately identify C. auris, or actively screened for it, and so this may represent under reporting. A routine whole genome sequencing service is not currently available for typing, although it can be undertaken linked to specific outbreaks. Hopefully this will be up and running soon to better understand how the different clades discussed above are represented in the UK, and whether any of them are linked to more challenging outcomes than others.

Where do we find it?

Due to its global distribution, overseas patients may also be at increased risk of introducing C. auris into UK healthcare settings, with one centre reported 1.6% of their overseas admission detected as colonised, with patients coming from the Middle East, India and Pakistan, showing higher levels of recovery.

UKHSA guidance suggests we should screen any patient who has had an overnight stay in a healthcare facility outside of the UK in the previous year, as well as patients patients coming from affected units in the UK. This sounds relatively straight forward, but it can be challenging to identify patients who have had an overnight stay overseas on admission if they are not being admitted from overseas. It also relies on clear communication from other centres that they have an issue, if we are to screen patients from impacted units. Many centres have therefore decided to screen all patients on high-risk wards, such as intensive care, to address some of this unknown risk.

Risk factors for developing C. auris colonisation or infection should be considered when deciding on screening strategies and the list within the UKHSA guidance includes patients who have experience:

- healthcare abroad, including repatriations or international patient transfers to UK hospitals for medical care, especially from countries with ongoing transmissions

- recent surgery, including vascular surgery within 30 days

- prolonged stay in critical care

- severe underlying disease with immunosuppression, such as HIV and bone marrow transplantation

- corticosteroid therapy

- neutropenia

- malignancy

- chronic kidney disease or diabetes mellitus

- mechanical ventilation

- presence of a central-venous catheter or urinary catheter

- extra-ventricular CSF drainage device

- prolonged exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotic or antifungal use

- underlying respiratory illness

How do we find it?

Screening is undertaken by taking swabs from the axilla (armpit), groin and nose, although different patient groups may require additional screening. Patient surveillance is important for two reasons:

- 1) to understand which patients are colonised in order to introduce additional precautions to limit risk of transmission to other patients or the environment

- 2) to support improved patient management but allowing patients to be put on the most effective antifungal if they go on to develop any signs of yeast infection, in order to improve outcomes

If a patient is detected as positive, other screening sites can help manage individual patients and so UKHSA say additional site screening should be considered:

- urine (especially if there is a urinary catheter in-situ, including intermittent self-catheterisation)

- throat swab

- perineal swab

- rectal swab (in paediatrics we would consider a stool sample instead)

- low vaginal swab

- sputum or endotracheal secretions

- drain fluid (abdominal, pelvic or mediastinal)

- vascular access sites

- wounds or broken skin

- ear

- umbilical area (neonates)

Swabs should ideally be processed on chromogenic media (colour changing agar plates) and fungal colonies confirmed using MALDI ToF or a validated PCR (my previous post on PCR may help with this). It can also be helpful to incubate plates at 40oC, as C. auris can grow as much higher temperatures than its Candida cousins, which can help with identification. If grown then the yeast should be stored in case you need them for future typing to help in understanding transmissions or outbreaks.

Why should we care about it?

Due to the high mortality rates for patients who develop infections, and the issues with choosing antifungals that work, it is really important that we know when we have patients who are colonised with C. auris. Controlling spread, even if patients don’t become infected, is incredibly important for the individual. This is because if a patient is detected as positive they won’t be de-alerted (have IPC precautions stopped) at any point and so it will impact them for months, if not years. These IPC precautions include isolation (keeping separate from other patients), and sometimes only being nursed by specific members of staff. These patient and staff impacts are so significant they’ve even been acknowledged in popular media, with a three episode arch covering C. auris in The Resident on Netflix (season three, episodes 18, 19 and 20).

Are there differences in how you might treat?

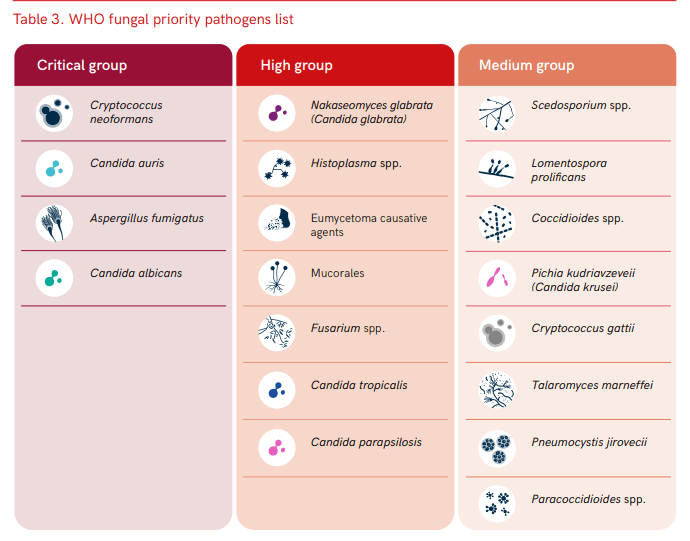

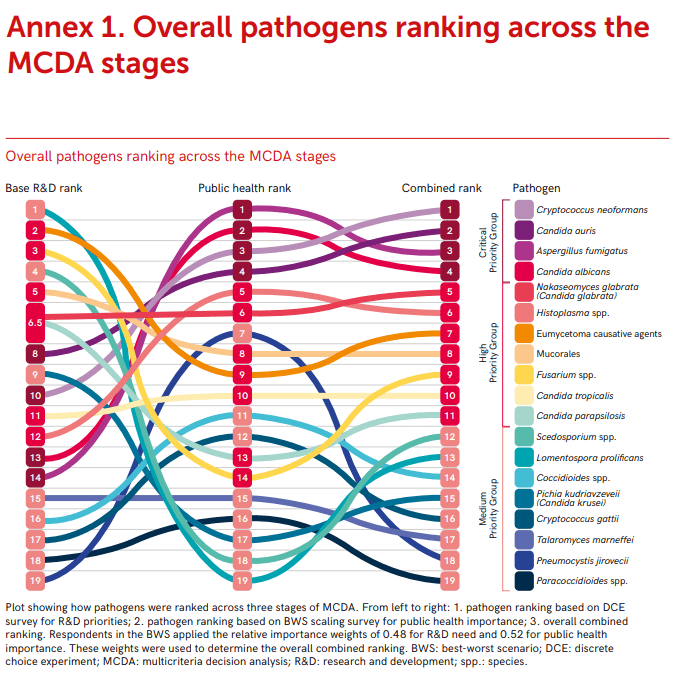

As I’ve already said, C. auris is pretty resistant to treatment compared to its Candida cousins. UK data indicates that isolates are resistant (don’t respond to) to the normal first line treatment of fluconazole, and often to other antifungals within the azole class. Some isolates have been resistant to other commonly used antifungals, such as amphotericin B (20%) and echinocandins (10%). Resistance to other antifungals can also occur whilst infections are being treated, and so it is important to monitor sensitivities (whether the drug works) and send to reference labs in order to understand the most appropriate therapy. Its resistance profile is one of the reasons the WHO have highlighted C. auris as a priority fungal pathogen for further research and to highlight clinical risk.

Its not just antifungals that are important however, antimicrobial stewardship is important in general, as prolonged exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics and antifungal agents are risk factors for both C. auris colonisation and infection (again this links back to the high risk patient groups impacted). Therefore, doing a better job of monitoring and controlling antimicrobials in general is likely to have a beneficial impact on C. auris risk.

Challenges with environmental control

One of the many things I love about the new C. auris guidance is its focus on multidisciplinary input ‘Healthcare workers are encouraged to work in multi-disciplinary teams, including Clinical Infection Specialists and IPC teams, to risk assess and support the management of patients infected or colonised with C. auris‘. I think this is so important, especially with an organism that is so challenging and can present such a high risk.

Environmental control is a particular issue for C. auris as we know it’s ability to survive and can grow at higher temperatures than many other fungi, means that it is likely to survive well in the environment. It also has the ability to form environmental biofilms, which can mean it is difficult to impact effectively using standard cleaning techniques, and once within the environment has been been detected for 4 weeks.

Within the UKHSA documentation, environmental contamination for C. auris has been found on the following surfaces during outbreaks:

- beds, bedside equipment, bedding materials including mattresses, bed sheets and pillows

- ventilation grilles and air conditioning units

- radiators

- windowsills and other horizontal surfaces

- hand wash basins, sink drains and taps

- floors

- bathrooms doors and walls

- disposable and reusable equipment such as ventilators, skin-surface temperature probes, blood pressure cuffs, electrocardiogram leads, stethoscopes, pulse oximeters and cloth lanyards

Basically most of your healthcare environment, whether fixed or movable features. In order to help stop the transfer from patients to the environment, via staff, the use of personal protective equipment is really important. Therefore the use of gowns and gloves is suggested. Single use and disposable equipment should also be used whenever possible, and patients should be kept in single, ensuite rooms, to minimise the risk of C. auris escaping from within the bed space to adjacent clinical environments. Any items within the space should either be cleanable with a disinfectant, or disposed of after a patient leaves. One thousand ppm of available chlorine should be used for cleaning, but needs to be used in concert with an appropriate contact time if it is to be effective.

Outbreaks

Most detections of C. auris cases detected are colonisation rather than infection (though colonisations can lead to subsequent infections). Within the UK there have been 5 significant outbreak of C. auris, each with over 50 cases, in addition to many sporadic introductions of single cases, frequently from overseas. Many of these have been in London or the South of England, and have resulted in considerable disruption to services over a prolonged period of time. This disruption can, in itself, be a risk to patients as it can result in delayed access to care. Outbreaks are also financially significant, with outbreaks reported as costing over £1 million for a service impacted for 7 months.

Although outbreak numbers are currently small, they are becoming more frequent, and even if infrequent have significant impacts. The need to control this risk before it becomes endemic within the UK health system is therefore significant. It is crucial therefore to collect more data and understand transmission routes of C. auris better.

Despite probable under reporting, it is clear that C. auris is becoming more common within UK healthcare settings, and has the ability to both cause significant issues for both individual patients and for services, due to outbreak impacts. Although fairly new on the scene there is increasing recognition of how C. auris could change fungal risks within healthcare, and even long stay residential settings. If we are going to adjust approaches in order to react to the new risks C. auris represents we need to both update our current practices, and invest in research, in order to learn how to do things even better. This is the reason that it feels important to share a post that is a little more technical than normal, both to help myself by learning more, but also to ensure that we are having conversations about an organism that has the ability to impact us all.

All opinions in this blog are my own