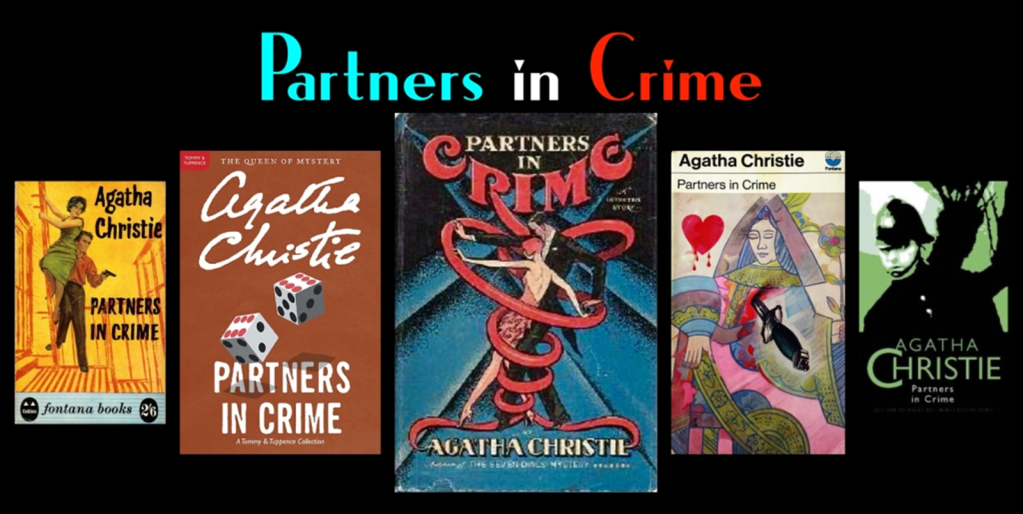

This weekend I’m off to Torquay for the Agatha Christie Spring Literary Festival. It will involve talks, a statue unveiling and even a ball! Some of you will know that I’m a massive Agatha Christie fan and love a good murder mystery. It’s part of the reason my ambition for when I retire is to finally have time to write some of the pathology murder mysteries that I have drafted out. I’m planning a three book series called The Murder Manuals. Anyway, that’s some way off but I still love to indulge in a bit of Agatha joy.

Whilst thinking about it this weekend, when I should have really been packing instead, it occurred to me that maybe one of the reasons that I love my job so much is because, in many ways, working in Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) is like working to solve real life mysteries and challenges on a daily basis. You come into work every day not really knowing what the future will hold and spend your days trying to uncover who the criminals (microorganisms) are and how to prevent future ‘crimes’, in the form of infections. This feels even more true having recently posted about how a forensic science lecture I went to looked at solving crimes. So, whilst my head is all linked to the detective process (I suspect I’m more Miss Marple than Hercule Poirot, although really I’d love Mr Girlymicro and I to be Tommy and Tuppence) I thought I would write about why I believe IPC professionals make the best healthcare detectives.

Beginning at the end

Like most good crime dramas, we in IPC, often make our entrance towards the end of a story when we things have already happened. We then have to work backwards to understand what’s happened as well as working forward to prevent any future risk (‘crimes’). Now, the point we get involved can range a bit. Just like in detective dramas, if the crime is obvious the police get involved early. Sometimes however, Miss Marple suspects a crime has occurred (think Sleeping Murder) but everyone else can be slow to get onboard.

In the world of IPC sometimes there are very clear events that need to be looked into. An outbreak for instance is traditionally described as 2 cases linked in person, place and time, or a single case of a significant infection, such as Ebola. This works pretty well most of the time but there are circumstances where using this definition can mean it takes you longer to identify an outbreak, or ‘crime’, has occurred. An example of this is when outbreaks are linked to an intermediate environmental source. This means that you may have low level numbers of cases which don’t appear to be linked in time, or even person, but are just linked to location. I’ve written about the importance of environmental IPC before, but this is one of the reasons it can be particularly tricky.

Need to understand the rules

In every detective story there are rules. If you’re in a Christie novel there will be a denouement, if you’re watching Columbo you will always see the murder at the start, and if the murderer is a female she will always be the person Morse tries to flirt with badly at least once. Infection Prevention and Control is no different. There are unwritten rules that you need to learn and which will help guide you on your way. Vancomycin Resistant Enterococci outbreaks will often have an environmental component. Norovirus outbreaks within staff often have a secret staff member who vomited in the toilet and told nobody. Pseudomonas aeruginosa outbreaks make people ask ‘have you checked your water?’ All of these things give you a way to start investigating and a set of questions to begin with.

Now, here comes the word of warning. Just like The Murder of Roger Ackroyd broke the rules, so do bacteria and other outbreak causes not always behave the way they are supposed to. Just like any good police drama with a rebellious detective, you need to know the rules but also know when to ignore them. Know when to switch tack and think that your MRSA outbreak may actually be linked to your ventilation system, not direct hand to patient transmission. Be neutral enough when looking at your data to not ignore the clues that are there. Red herrings will be present and distract you, so know when to call a fish a fish.

Start broad and narrow down

One of the best ways, with any investigation, is to start broad and narrow down. This enables you to avoid diving down rabbit holes and missing other pathways that should be investigated. Very rarely can you turn up to a country house murder and exclude most of those present, and as Hercule Poirot famously states “it is always wise to suspect everybody”, and the same is true with IPC investigations.

Ask yourself, why do I think that there’s something happening? How do I know that cases occurring at the same time are actually linked? How are my surveillance systems set up to support identification of low levels of cases over prolonged periods? How sure am I then that a ‘crime’ has actually been committed? Once the body as been found, in terms of looking for sources, where do I get my information from? Do I consider just other patients, or patients and families, or patients, families and the environment, or even patients, families, environment and staff. This, all before you even start to consider how different organisms behave in different types of patients. In a country house murder you need to consider those above stairs as well as those below, and in stories like the A.B.C. Murders, you even need to consider those who came and rang your doorbell.

There are so many moving parts within healthcare and we need to ensure that we are capturing as much of that landscape as possible when we start our investigations. Starting broad supports this, but you also then need to know the key moments to start excluding options so that you can eventually get to the depth needed to support interventions and change. Eventually you have to have the scene where you commit and name the murderer. Within IPC, events such as outbreak meetings can really help with this, as unlike our favourite detectives, we can’t keep all the information to ourselves right to the very end. These meetings bring people together to both help gathering information but also to decide on how to focus next steps.

A plethora of unreliable witnesses

In A Murder is Announced Miss Marple states, ‘Please don’t be too prejudiced against the poor thing because she’s a liar. I do really believe that, like so many liars, there is a real substratum of truth behind her lies’. One of the things that is often quite difficult to pin down during IPC investigations is….what is the truth? Truth is often seen as definitive but in reality truth relates back to the lens through which the individual sees the world. For instance, if you asked me what I was doing at 7am last Wednesday I wouldn’t lie, but I would have to offer some form supposition as I can’t actually remember precisely. The other complication is that those directly involved may be even less able to recall their own roles. If I’m sick in hospital days can merge into one and I’m focussed on my physical reality rather than taking in my environment. This is all before we take into consideration the fact that we may be providing sedatives and other medications that could impact recall. Would I remember that one of my visitors mentioned my niece had diarrhoea……..probably not.

Within IPC investigations no one is likely to remember every physical action, which is why audit can be a helpful addition, in order to have an external person capture trends. In other scenarios the actual witnesses to the event can’t speak, for instance ventilation gauges that may have fluctuated or alarmed (is that a voice?) to an event that no one wrote down or reported. This is especially challenging when you are trying to get to the bottom of grumbling outbreaks that have been going for some time, but also is a particular challenge linked to infections with organisms that may not become apparent for months, such as some surgical site infections or infections with pathogens like Aspergillus. Memory can make individuals particularly poor witnesses in these scenarios and good record keeping and notes are essential to support look back investigations (investigations where you are looking back to capture risks and event detail).

Need to know which tools to use

If you only interview half of the witnesses in your case, you’ll be lucky to get even half of the story, as it will all depend on which people hold the information. On some occasions you will luck onto all the answers with the first witness, but is this a risk you want to take? The same can be true in IPC investigations if you don’t think about the tools or sampling methods you want to access from your toolkit. Is your main focus on using bacterial culture? Do you have a method that will work even if the patient is on antibiotics? If you are looking for a viral cause, what method is best? PCR is not PCR is not PCR. You can look for RNA, or DNA, you can extract from different volumes and different types of samples. The pros and cons of all of which need to be considered. Putting together a sampling strategy in response to an investigation is like choosing the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle whilst knowing that you are not going to have all of the bits. You want to choose pieces that give you the best chance of accurately guessing what the picture is.

In IPC there are various pieces of documentation that will help with thinking in this area. Documents like the UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations (UK SMIs) can help guide thinking linked to which samples might be useful to take. UKHSA also has various documentation linked to outbreak investigation with specific organisms and interpretation criteria, such as measles, C auris, and TB. At the end of the day however, just like your detective walking into a murder scene, you will need to work out how to apply that guidance to what you see in front of you.

It’s all about the clues

Once you have investigated and questioned your witnesses then you need to be able to work out from your clues which pieces are useful and which are your red herrings and may lead you astray. Like all investigations the most important thing is to be methodical but you then need to make time to be able to think and reflect. Poirot famously once solved a case without leaving his front room, just by being able to sit and question those involved. I’m not saying that this is something we should try in terms of IPC, but I do think it holds some lessons for us about the power of thinking time. Especially when you are in the midst of an outbreak there is often a real drive to be seen to be doing something, responding to everything, and constantly doing more. After 20 odd years in micro/IPC I think I’m beginning to think that Poirot may have been onto something.

If you are constantly changing or adding in responses it can be really difficult, even if you reach resolution, to know which thing you did made the difference. Early on in an outbreak it can be easy to rush into making recommendations prior to having gathered all the information you need. It sometimes feels good to call an exposure meeting the minute you get the information that an event has happened. For instance, you may have days to respond in the case of something like a chickenpox (incubation period 8 – 21 days), before those patients become a risk to anyone else. Therefore waiting to call a meeting until you have gathered all the clues, until you know everyone’s immune status, levels of exposure etc, can mean that your meeting is so much more effective in managing any risk. Waiting until you have a decent action plan for where you might search for clues, i.e. sample, may mean you find the answer so much more quickly then having to go in for multiple attempts. Taking a breath and putting thought before action may mean you get to the final result so much faster. So utilise those Little Grey Cells!

Not everyone takes kindly to be investigated

IPC should not be about blame, but just like the house guests in a country house murder may not take kindly to a visit from Inspector Japp, some occupants of your ward may be less than happy to see IPC walking up to the nurses station. Although I talk about the similarities between IPC and detectives, we should not be feared and act like police, or worse than that judiciary. Often the reason why Jessica Fletcher gets further faster in finding the murder than the police at the scene is because she is seen as just another friendly visitor rather than someone looking to find fault. Her focus is on building and utilising relationships in order to gather information. She is often seen by the other witnesses involved as being part of their team, and the outputs of her investigations are often linked to co-production of outcomes by sharing information, rather than going it alone.

In general, as in many areas of working life, relationship building is key. You see Jessica all the time in Cabot Cove, not just when there’s been a murder. That means that by the time she finds the body she already knows most of the players and has built up relationship capital with those involved. This enables her to sometimes ask the challenging questions. I believe the same needs to be true for IPC. If clinical teams only see us when things go wrong, they are automatically going to be somewhat defensive. If they see and work with us when times are going well, as well as less well, they are more likely to feel we’re in it together with shared ownership. All of which means we may also get to the source that much faster when we need to.

Sometimes there’s a twist in the tail

There are a number of famous Agatha Christie stories where the murder victim turns out to not actually be dead, I won’t spoil them here. The same can be true for IPC cases. There are certain organisms, of which Adenovirus is my personal favourite, that can both cause primary infection and then go latent and reactivate later. Often this reactivation is linked to immune status, and of course many patients in hospital have immune systems that are doing less well. These present challenges as you can look like you have a cluster of cases but, due to the type of patient, they can all be independent findings that happen to cluster together. So, without the right investigations you can call ‘murder’ when actually there is no corpse. Being happy to hold your hands up and step down when you have new information is an important trait, but knowing to get the testing done to enable you to do so is even more so.

The other scenario that can happen is, as Sherlock Holmes famously said, “When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth“. There will be things that have been done, behaviour that has occured, that you would never imagine or predict. Over the years I’ve found a lizard in a bathtub, olive oil used as skin care by parents, and all kinds of things in fridges and freezers, just as the tip of this iceberg. Things that out in the real world would probably not be a risk, but in the healthcare world can lead to all kinds of issues, none of which would be on my primary list of questions when trying to identify a source. The world continues to surprise me, and therefore in the world of IPC keeping enough of an open mind to to respond to the unexpected is essential.

It’s a team sport

Poirot has Hastings. Morse has Lewis. Sherlock has Watson. Tuppence has Tommy, and Jessica has most of the population of Cabot Cove. Solving crimes benefits from teamwork and IPC is no different. I’ve spoken about the importance of relationship building but doing IPC investigations well benefits from more than even that. One of the key ways these partnerships work is by creating the space where the discussion and reflection we’ve already talked about can happen. In healthcare, which is far from a contained setting with only a handful of key players, being part of a team can also provide vastly more eyes and insight into what happens in reality.

The Hawthorne effect is a type of human behaviour reactivity in which individuals modify an aspect of their behaviour in response to their awareness of being observed

One of the reasons that it’s important to undertake a team response within IPC is that if I turn up, a stranger or less frequent visitor on the ward, then those on the unit may behave differently because I’m there. If you see IPC hanging around a sink, for instance, then you may suddenly focus way more on your hand hygiene efficacy then you would otherwise. If I go to speak to a family, they may say different things to me than they would to the bed space nurse they see everyday. In order to get the full picture I may not always be the right person to ask the questions. Being fully integrated, being seen as part of the team, or having relationships with people that are, can make all the difference in terms of the success of your activity. Everyone benefits from having a Hastings to send in to ask questions from time to time.

No greater satisfaction than being part of the denouement

I don’t know about you but I just love the moment that everyone gathers at the end of a Christie novel and detective starts the process of walking everyone through all of the different clues, red herrings, and witness statements. The moment when you discover if you’ve picked up on everything that was on offer to you, and even more than that, the anticipating of waiting to hear if you’ve put it all together in a way that a) works and was b) actually correct.

I feel the same way when I finally have that moment when I crack the case, when I find the source, or even just get to the point where I understand a tricky result. The hallelujah moment when you look down at the jigsaw pieces you have and you can finally see the full picture. It’s the reason that some of our favourite investigative successes live on for years in teaching and case studies. I will talk about the case of the Norovirus and Biscuit Tin to anyone who will listen even now. The settings may be different but every detective, whether in a novel or in healthcare, loves to regale others with their exploits. We just can’t help ourselves. My excuse is that sharing the learning helps is all. That said I’m off to attend a talk called ‘How to kill people for profit’. I’m assuming it will give me all the tips I need to be the next cozy murder success and maybe even weave in the odd IPC detective drama moment into the mix.

All opinions in this blog are my own

[…] also went back to some of the activities that I used to take for granted pre-pandemic. I went to a literary festival, I went to science events, and I even returned to a gaming convention. These events reminded me of […]

LikeLike