Back in the mists of time, before she really knew what microbiology was, there was a girl who just knew that she liked science. Now, this girl had a father who liked physics, a sister who liked chemistry, and a brother that liked both. This girl was not particularly found of mathematics however, and chemistry was a foreign language, and so she starred in the lab and wondered,’What kind of science is right for me?’.

I have previously posted about having missed so much school and not really being prepared to go to university. I didn’t, therefore, have exactly the most normal build-up to uni as I didn’t think it would happen. In a rather spectacular science irony, when it suddenly turned out I might be able to go, I just hadn’t done my research. I didn’t have much of a clue what my options or routes to a scientific career might be. Hopefully if past me found my how to be a scientist blog it would be a useful starter for 10. In my defence, at least I acknowledged this, and so I chose a degree that allowed me to specialise after my 1st year, when I would have had time to try out a few potential options.

One of the other things I should probably admit at this point, is that lab work terrified me. I hadn’t been in the class room when people were shown how to use microscopes or pipettes, and I was just too embarrassed to ask as I already felt both stupid and so behind everyone else. I’d done very little lab work as I’d missed most of my 5th year at school, and during my A-levels I had to undertake condensed study to make sure I had enough points to go to uni. So the idea of spending a lot of time outside a traditional lab space definitely held appeal, as it felt like I was finally starting at the same point as everyone else.

So this girl finally chose her specialty and worked super hard to be accepted onto the zoology course.

All of this feels like a different world at this point, over 20 years on. As some of my team love to point out, I started uni when they were still at primary school (1999). These years were so formative however for how I developed as both a scientist and a person, I was so excited to be able to revisit the subject when I spent a night at ZSL London Zoo with Mr and mummy Girlymicro and remind myself of days of science past.

What is zoology anyway?

When you say Zoology, I suppose the first thing that springs to mind are zoos. Now, you may find quite a lot of zoologists in and around zoos, but this is actually just one place place where the study of Zoology happens. In fact, zoology is so much more than the study of animals in zoos. It is, in fact:

The scientific study of the behaviour, structure, physiology, classification, and distribution of animals

I was aware that the area of animal behaviour really interested me. It was something that I’d touched on during psychology A-Level, and that then extended into human behavioural modelling with things like group decision making. Comparison of group behaviour between primates and other animals and how attachment develops between adults and infants was something that I found fascinating. This was, for me, the gateway that made me think about choosing Zoology, but there was so very much more to it than I knew at that point.

Because of this, when we arrived to spend the night at London Zoo, I was particularly excited as the lion enclosure had just welcomed three cubs, one girl and two boys. Mali and Syanii and girl Shanti were born at London Zoo on 13 March 2024 to seven-year-old mum, Arya, and 14-year-old dad Bhanu. The first thing we got to do was to spend some time after the zoo had closed watching them at their most active, as it was evening, in a small group with one of their keepers. We got to drink prosecco, take all the photographs we wished, hear a talk, and pepper them with questions. It was a truly wonderful way to kick off the evening. It was also as far away from my old zoology field trips as you can imagine, where as a student I would find the most comfortable spot on the ground I could in order settle in for the next eight hours, with a pile of stationary and a timer, nursing a bottle of water and a sandwich so I didn’t have to leave my space until I was done.

What was the degree like?

One of the great things about the degree was that, as long as you took the correct modules for your target specialism, you could try all kinds of science topics, especially early on. So, as well as modules on invertebrates and ecology, I also took modules on psychology and microbiology. In my first year, although I feel it disliked me as much I disliked it, I also took mandatory modules, which included Biochemistry. That first year was a whirl wind of things I was unfamiliar with. It was also the year that, although I thought I liked human genetics, I discovered that it really wasn’t the field for me. I learnt a lot about how I think and what kinds of topics align better with how that process works for me. A version of the course exists even now if anyone is interested, although I suspect it has moved on somewhat:

https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/courses/2025/zoology-bsc-hons

Now, I was still terrifed of lab work and so the fact that some modules came with weekend field trips rather than traditional lab work made me very happy. There were also other kinds of ‘labs’ which involved a lot of drawing of skulls and anatomy, where I discovered I hadn’t missed my calling as an artist.

There were also some super super fun exercises that I remember fondly even now. At one point we were sent out to learn how to capture and undertake population statistics by recording taxi cab license plates (as they link to age) and working on the population stats of births and deaths using this. I found a lovely window in a McDonalds and stared at a taxi rank for a day chatting with my friends, and it was great. These moments really taught me that science was not all about lab work, as I had previously thought, but it could be undertaken anywhere and in a way that was not only interesting but also enjoyable and fun.

One of the other things this course taught me about myself was that I like to take the less trodden path. For my final year dissertation, I could have taken a lab based project, but I still wasn’t that confident. Instead, I chose to do a library based project with a twist. The library was the British Library (https://www.bl.uk/), and the project was based in evolutionary psychology looking at The Demographics of Witchcraft Accusations (1625 – 1720). I got to go through every documented witchcraft trial in England and then look at the legal changes that drove resource competition and compare it with the US and Europe, where the drivers were different. This exercise stays with me, as it showed that no matter what the outward appearance, you always need to understand the underlying drivers to fully investigate a situation.

Moments that stay with you

I’ve already said that my aim was always to choose Zoology because of my interest in animal behaviour, but it was a pretty competitive selection process. Places were allocated to specialisms on the basis of a combination of choice and grade. So the top person in the year was guaranteed their choice of degree, if you were 300th, not so much. I believe my 1st year had over 1000 combined students, and the bottom 50% were dropped every year, so the year group size got smaller but was still competitive. Dissertation topics were given out in the same way. So there was an ever-present motivation to work hard, not just so you didn’t get booted, but so you could have the best chance to influence your future. I suspect it’s all very different these days with tuition fees, but it was pretty brutal for some people.

If you secured the grades you progressed and specialised. This meant we got to do some zoo visits and start exploring topics like animal behaviour and undertake behavioural observation studies. Several of these were zoo based and included observing primates, but also Giant Tortoises. We also did a fair amount of non-zoo based observational studies, including undertaken observations in the uni canteen looking into group and sentinel behaviour.

I loved this mix. I love the fact that it really embedded science for me as a team sport, as so much of it you couldn’t accomplish on your own. It also taught me how much I value both collaboration and variety in what I do, a valuable lesson in choosing my future career.

In all honesty, over time, despite loving the science I grew to believe that sitting in fields in the lake district wearing water proofs for weeks at a time was less aligned with my future life choices, but at least it gave me fun memories that years later I could turn into a comedy sketch as part of public engagement work.

How did all of this help with the day job?

This was all very fun, but how does any of that help me now?

Well, I obviously covered a certain amount of animal related infection, which is still useful, but I think it was the wider stuff that gave me such a good foundation for every day working life as a scientist.

Firstly, there was always a strong focus on group communication. You just couldn’t succeed on the course without developing your group work and collaboration skills. Almost everything we did required multiple people to support. You can’t observe a group for 8 hours on your own, at least not efficiently. This meant the planning and analysis stages also involved a lot of group discussion. Being young and enthusiastic, there were lots of strong and differing opinions. Learning to manage in those environments has been a crucial skill that has supported working in healthcare and multi-disciplinary environments later on.

Due to the variety of different types of work, I also got used to needing to access information from all kinds of different resources and from a lot of different disciplines. One day, I would be accessing psychology or physiology papers, and the next, I would be in a field reading ecology guides or in the British Library accessing centuries old court records. This also taught me the value of being a generalist with a solid supporting skill set. I don’t feel like I will ever be a real ‘expert’ in anything, but I learnt to take things from 1st principles and rationalise my way through. This is an approach I will be forever grateful for as so much of what I see in my day job I haven’t experienced previously. Getting back to 1st principles is something I have to do often and this training enabled me to do that without fear of the unknown.

Finally, the whole process of struggling to get to uni when it was generally considered to be ‘not for me’ and spending a lot of my time there feeling behind and playing catch up taught me a lot of things that are so valuable in my day today. It taught me to see science as a puzzle, and that to solve something you sometimes have to give it space and come at problems from different angles. During these periods it also taught me to be comfortable with being uncomfortable, and knowing that uncertainty is OK, in fact it is often essential. The very way the course was structured also gave me permission to mix up my science and follow routes that interested me, not some pre prescribed path. I think keeping to this principle has been key to me ending up where I am career wise. Follow your passion and the rest will work out, has become a guiding principle when I’m undertaking decision making.

What is a zoonosis?

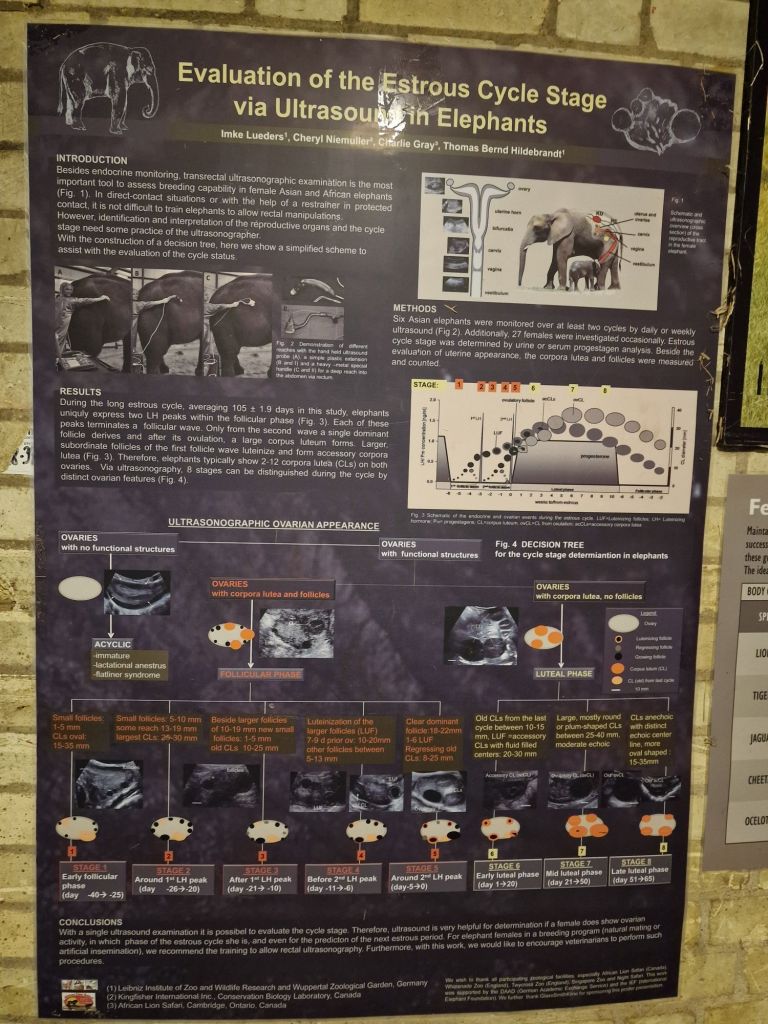

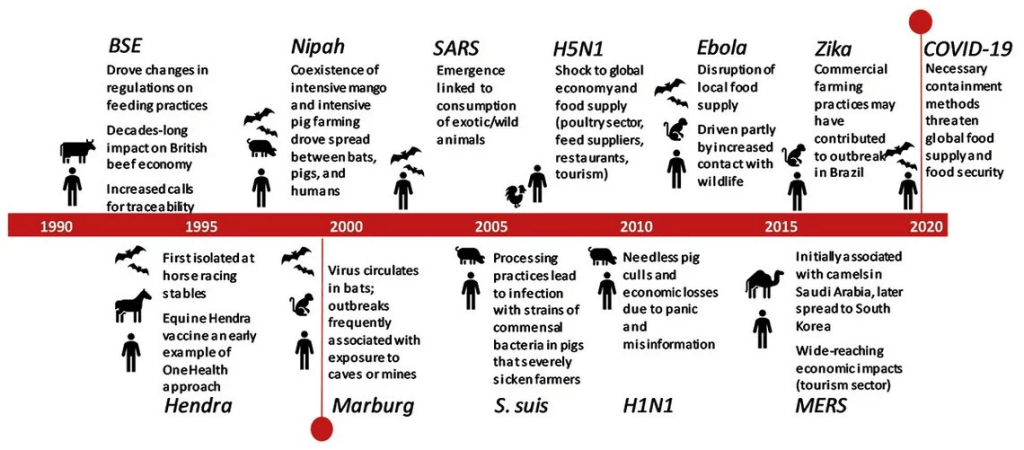

Speaking of things that help the day job, I spent plenty of time in my third year studying infections related to animals and animal to human interaction. One of the other great benefits of a background in Zoology is the fact that, having learnt things from the animal side, I can combine that learning with the info I now have from the human side. Zoonosis are an increasingly important part of health based conversations, especially in light of increased travel, climate change, and urban expansion. So, what is a zoonosis?

A zoonosis is an infectious disease that can spread from animals to humans, or vice versa. Zoonotic diseases can be caused by a variety of pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoa, and prions.

There have been multiple occasions during my career where zoonosis have been flagged as causing wider public health implications, and some of the big hitters are listed below:

One of the other reasons why zoonoses and a background in Zoology are increasingly important is linked to the One Health approach to antimicrobial resistance (AMR). This requires us not to look at AMR from a purely human or animal perspective, but that we need to look at food production/agriculture, human and animal, as a holistic whole. I’ve recently been involved with a podcast series that involved discussing One Health issues with a vet, Simon Doherty, called going Macro on Micro, and hearing the veterinary perspective has been really helpful and eye opening.

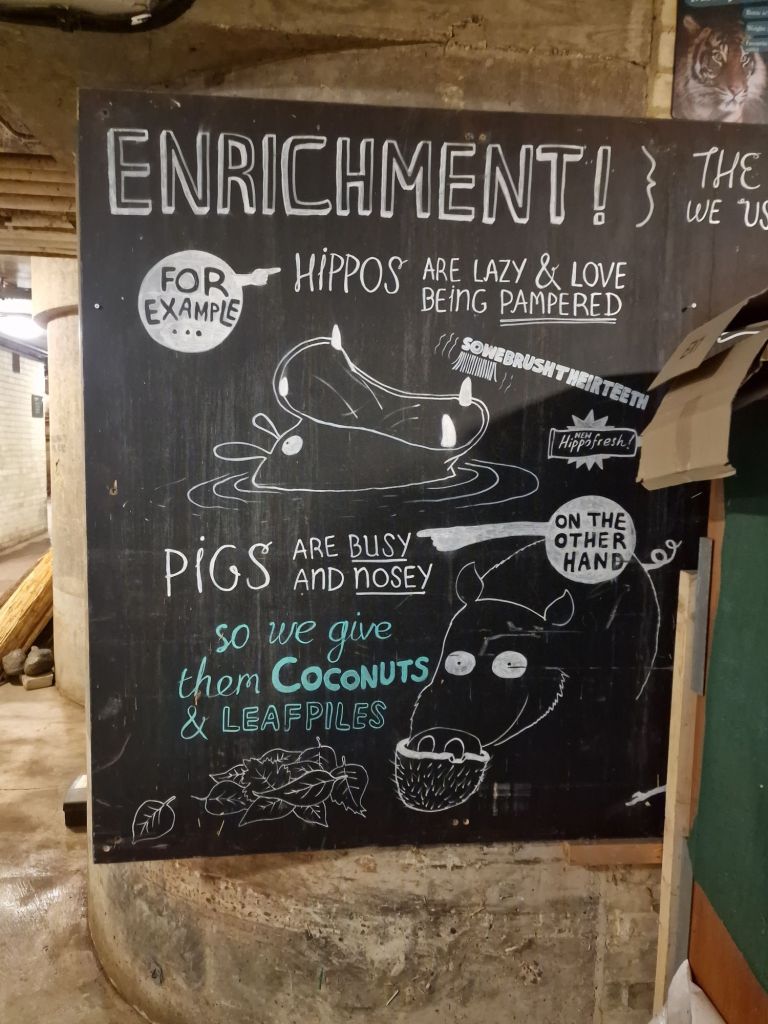

Embedding public engagement

One of the things that I loved about staying overnight at London Zoo, apart from it reminding me of a joy for science and of fond memories, was the way that science and science engagement was embedded wherever you went, from the toilets to the canteen. Not only was information wherever you looked, but it was done in such a fun variety of ways, including an entire focus on poo, which was brilliant to see. It was science delivered in an accessible, engaging way that didn’t feel like you were being ‘taught’ but that you learnt through play and exploration.

This is such a great lesson for all of us involved in teaching and education, in both formal and non-formal settings. Learning can be achieved without it being arduous and by enabling those visiting to understand that science can be fun without it feeling ‘other’ or out of reach. It is the best way to introduce a generation of future scientists to the subject. Work such as this, also goes a long way to break down stereotypes of what science is (often considered to only be lab based) and what a scientist looks like (often considered to be the realm of older white men). In reality, science is for everyone, undertaken by everyone, and takes place everywhere. Embedding this concept early is the best way to change how science will be perceived in the future.

A peaceful escape

To end, I just wanted to quickly talk about what a delightful experience staying over night was. I am not a camper, and I am barely a glamper. I want an en-suite bathroom and a proper bed, with the ability to have tea whenever I want it. Fortunately, the cabins at London Zoo provide all of these things.

They are set in a zone of tranquillity, that whilst surrounded by the zoo, do not in any way feel impacted by the hustle and bustle of those visiting. That said, you are also in the centre of the zoo, so all of the walking tours around do not feel like you are walking miles im order to explore. You also get to undertake some activities that you simply wouldn’t be able to do any other way, including preparing enrichment activities for the animals and feeding some of the nocturnal species.

Whilst staying over you get full access to the zoo the day before, and on the following day. You also get to have dinner together after the zoo closes and breakfast together before the zoo opens. There are two different groups of bookings, one that includes kids of all ages, and one that is targeted at older kids and adults. This enables some of the tour content to be targeted, and for our tour, the group consisted entirely of adults. It was such fun, I can’t recommend it enough, and it was great to share it with mummy and Mr Girlymicro. It books up fast though, so if you want a chance at this unique insight, it’s worth booking several months ahead.

All opinions in this blog are my own