Working in Infection Prevention and Control is basically about assessing risk. It’s pretty much what I do, what I eat and breath. So today I wanted to post (with that in mind) why I’m tired to the core of my being when I hear the joyful proclamations about the 19th July and so called Freedom Day, and it’s not just me others are definitely feeling it too.

This doesn’t mean that I don’t understand the strong urge to ‘get back to normal’. This is a very human trait. We all like to feel in control and this has been a prolonged period of high stress and uncertainty. I suppose my frustration is with the failure to really communicate that normality comes with a cost. It will likely bring economic benefits but it will cost some people their lives and NHS workers just a little bit more of their sanity. If as a society we agreed that the economics were worth it I would grudgingly keep my mouth shut but we’re not even having the conversation. There is no such thing as a free lunch and at the moment society is passing me the bill when I’m not sure I’ve brought my wallet.

It’s All About the Shades of Grey

For cognitive comfort we tend to feel comfortable seeing the world in black and white. The reality is (as with most things) that the world and decisions are made up of shades of grey. It is possible to live in a world where we are neither in complete lock down nor where everything is effectively considered back to normal and presenting increased risk.

When I’m dealing with an outbreak in a hospital setting (I acknowledge the situations aren’t identical) I bring in a series of measures to find the source and stop transmission. Often because of the risk to patients and staff you do all these things at the same time, in order to maximise your risk reduction. Then once you have identified the source and stopped further cases being identified you gradually reduce your measures.

You do your intervention reductions in this way for a number of reasons:

- You often don’t know what is having the greatest impact so a step wise reduction enables you to learn more about how you might control a similar outbreak better in the future. You will know which interventions are most important.

- Reducing your measures one at a time enables you to continue to monitor your cases. If they come back you know you need to maintain that intervention for longer and maybe step down others with a lesser impact first.

- It tells you more about whether you have effectively dealt with your source without putting large amounts of people at risk again.

- It stops you going all the way back to square one if you aren’t where you thought you were. You’ve worked hard to get things under control, so you don’t want to return to where you have an escalating scenario.

Stopping basically all of your public health measures in one go, masking, social distancing, most contact isolation etc without taking a staggered approach means that not only are you rolling the dice on your main intervention (vaccination) working in isolation, but also you are failing to gather the information you need to support staggered reintroduction of key control measures moving forward if it doesn’t.

Risk Assessment and Personal Choice

One of the things that has really struck me is that we are moving from a place where that risk assessment and risk reduction is guided at national level to personal assessment.

In many ways there is nothing fundamentally wrong with personal risk assessment. We ask healthcare staff to do this in clinical situations on a daily basis. What do I mean when I’m talking about personal risk assessment. In healthcare it could be something like: You are going in to take blood from a 4 year old child. Before you go into the room you might gather the following information in order to assess the risk and take steps to reduce it:

- Is the child on its own?

- Do they react badly to needles – are they scared?

- Do you know the child? Do you have a relationship where they are more likely to trust you?

- Do you have safety needles available to reduce the risk of a sharps injury?

The difference with the government approach to risk assessment and personal responsibility is that we are asking people to do this who are:

- not necessarily used to undertaking this kind of assessment in relation to infection

- not necessarily accessing the information/evidence to enable them to make such an assessment

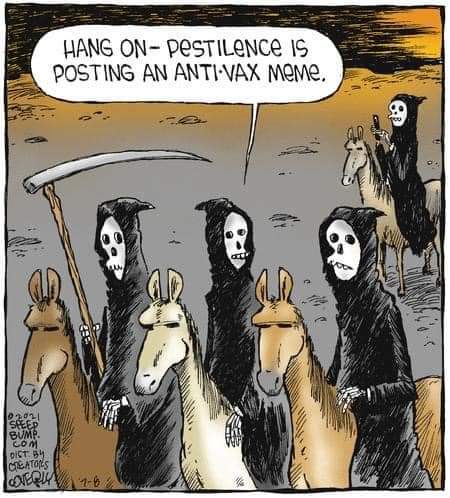

It is hard enough working your way through the information and evidence that is related to SARS CoV2 even if it is your job. We are asking the entire of England to be able to do this with little or no support. The quality of information out there is highly variable and often not context specific to make it particularly usable. There is plenty of misinformation out there which could lead to individuals with the best of intentions making bad decisions.

Mixed Messages

This then brings me onto the mixed messages. The government is telling people to use the evidence to make their own risk assessments and then supporting events that are contrary to a lot of the information we are saying is important in making those risk assessments.

The evidence still shows that masks will be important in confined spaces or in areas with high people density. We are at the same time encourage events where people in their thousands meet without those measures included. You can say that the research events are there so you could obtain data to improve future measures and risk assessments, although when only 15% of those attending complete the post event testing the outcomes become dubious. Outside of the research events however, large numbers of people are gathering in public settings, such as Trafalgar and Leicester Square, with no testing or monitoring. These events cannot be said to support the same goal.

It is not rocket science that combining alcohol and emotion can lead to the abandonment of key sections of the risk assessment process.

One of the other things we need to talk about is that personal risk assessments are fine, but in this particular circumstance your risk assessment and behaviour directly also impacts my risk. Mask wearing is about protecting others, so if you opt out of wearing a mask and I wear mine, I bear the brunt of your decision.

We are also not talking enough about how the knowledge linked to vaccination may impact on risk assessment. I know a lot of people who feel like SARS CoV2 doesn’t impact on them any more because they are double vaccinated. In healthcare we are seeing a lot of people who are still getting pretty unwell despite their vaccination status. They are not hospital unwell, but they are still pretty unwell, can’t get off the sofa unwell. They are also still able to pass on the virus to others in their household, at work, or elsewhere. Some of the people then exposed will not be able to have the vaccine, such as children or those with certain underlying conditions. They can therefore still get very sick. Again, the transmitter may not experience such extreme personal consequences but they can cause them for others.

The government messaging doesn’t strongly support prevention of harm to others. Personal choice makes it sound all about the person. A pandemic response however is about as much of a group effort as you can imagine mounting. Personal choice undermines all of what we have been trying to message and removes that shared responsibility.

If we are truly serious about supporting individuals to make their own risk assessments then we need to do a much better job of giving them a framework and high quality information in order to make it. We also need them to understand the consequences of making an incorrect risk assessment. I have no answers on this one, just anxiety and fear about where the current approach is leading us.

All opinions in this blog are my own

I think this is an intelligent, concise and pragmatic summation of the situation.

LikeLike