It’s been a tricky few weeks health wise, hence the lack of posts. I managed to come down with Norovirus, after writing a blog post about how much of it was out there. Post infection it sparked a whole world of inflammatory cascade symptoms that definitely did not bring me joy. I then followed it up by passing it onto Mr Girlymicro, who really wishes I’d stop bringing my work interests home with me.

All of this meant that I ended up having to take 3 days off work sick. During this time and for the week after, whilst feeling still pretty wiped out, every single little word in any messages from work, or even a lack of any, led me into a spin. Were people angry because I was off? Had I messed anything up that people were now having to fix? Was I being judged for not being on full form? The levels of anxiety that being away induced were so high, but let’s face it, in reality no one was really thinking about me.

Now I’m feeling better I am so aware of the fact that everyone was just focused on getting through their own days, dealing with their own challenges. My ability to rationalise and manage my perceptions were just highly impacted in those moments, and I lost the ability to remember that the Spotlight Effect is a thing. In light of this, and having just ridden the roller coaster of forgetting how this can impact, I thought it was worth taking some time to talk about the Spotlight Effect and its possible real world impacts on our leadership and decision making.

What is the Spotlight Effect?

We are the lead in our own dramas. By definition we should have ‘main character energy’. Being focused on self is therefore understandable. We are programmed to be the center of our own universe. It does need to be acknowledged, however, that this very positioning can bring with it a biased world view and set of perceptions.

Due to this natural tendency to be self centered we tend to interpret our worlds through the lens of ‘self’. We interpret communication and interactions with other people in a way that up playing up our importance in their worlds and down playing their own real life demands on how they interact with us. This is known at the Spotlight Effect.

This happens in positive situations, where we believe that colleagues may be more impressed by things that mean a lot to us, or over estimating relationships and the amount of influence we may have. The inverse is also true in terms of negative situations, where we believe that our failures or mess ups are noticed by others way more than they really are.

What does it mean for how you see the world?

This tendency to over estimate how much others notice or are impacted by us can really impact how we see the world. It means that we can end up agonising over an off hand comment, believing that we have offended or pitched something incorrectly, when the other person has not even noticed that the moment happened. I’ve written previously about how much I can spiral, and there is no doubt that the Spotlight Effect can mean that I spiral, wasting time and energy on something that is objectively not real. Wasting energy and focus on things that aren’t real means we can miss the real opportunities for change and learning in our lives, as well as meaning we are less able to live in the moment and really appreciate the good things we have going on. Plus, let’s be honest, the stuff is exhausting and I don’t know about you, but I don’t have energy to waste right now.

What does it mean for our interactions with others?

It isn’t just spiraling and anxiety that can result as a consequence of mis-interpretation of social cues linked to the Spotlight Effect. It can actively impact how we engage with our daily lives and relationships. It may mean that we avoid others unnecessarily, as we are keen to not have to deal with the imagined slight we caused. It may also mean that we hinder relationships by talking too much about our lives and our successes, and therefore fail to demonstrate enough interest in the lives of other people. Being unaware of how this ego centric approach can impact not just ourselves but others can mean that connections are driven towards the superficial, and that our ability to lead and influence is negatively impacted.

How does it impact bad days?

There are some really concrete ways that the Spotlight Effect impacts me. For instance, I should probably have taken the whole week off work as I was in a really bad state. Instead, due to the fear of phantom errors and fictional judgement I made myself go back early, thus continuing to drive the issue. There are definitely other ways that this phenomenon impacts me in general life, if sense checking doesn’t occur. I have a tendency to hide and withdraw from interactions, as I fear judgement. It’s easy for me to assume that someone being quiet or not interacting with me is because I’ve offended them or done something, when in reality they are just busy with their own lives, and if I reached out everything would just be as it always was.

It can also impact on how I handle conflict, partly because I will usually have played out all of the different conversations in my head beforehand, and yet somehow expect the other person to have been part of those imaginary conversations. This can, if unchecked, mean that my actions can cause conflict resolution to not go the way I’d hoped because I’m listening to social cues in my head instead of the ones that are present in front of me.

How does it impact good days?

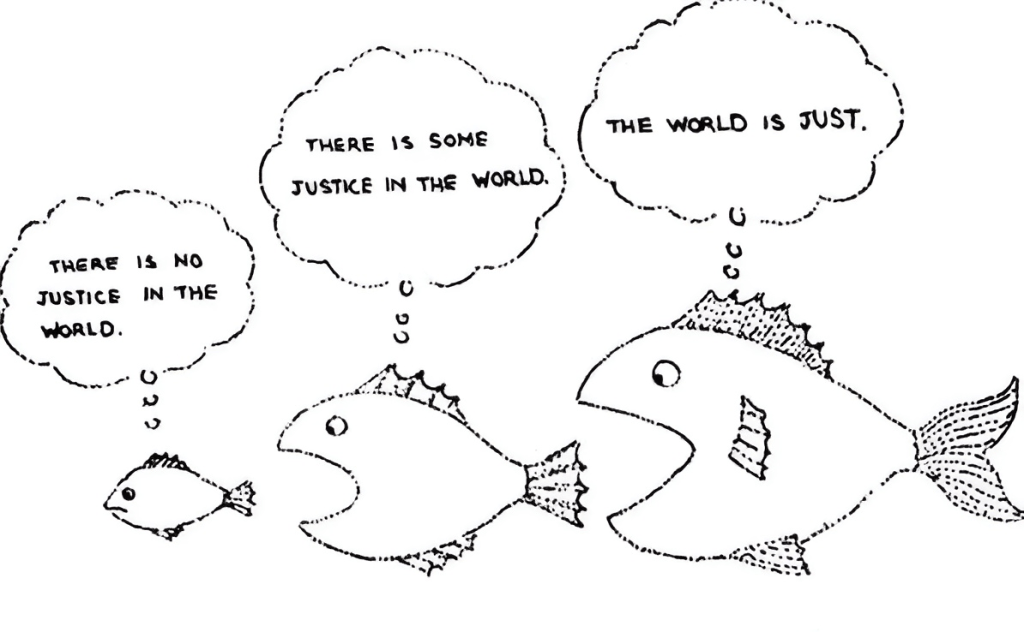

You would have thought that the Spotlight Effect would have it’s biggest impact on bad days and when you were already feeling anxious. I think the truth may be that actually the most damage can be done, if not aware, when things are going well. It can mean that just because life is going well for us, we assume that a) everyone else recognises and is similarly pleased for us and b) that life is the same for those around us, with everyone experiencing contentment.

In reality, this may lead us to not hear clearly enough what others have to say or think. We may miss clues that would have enabled us to understand challenges and anxiety in others. Thus losing the opportunity to address issues early. It can also mean that we feel over looked, as our accomplishments feel like they should be obvious to others, when in reality we just have assumed that everyone is paying as much attention to our careers as we do, which is obviously not the truth.

When does it mean for your leadership?

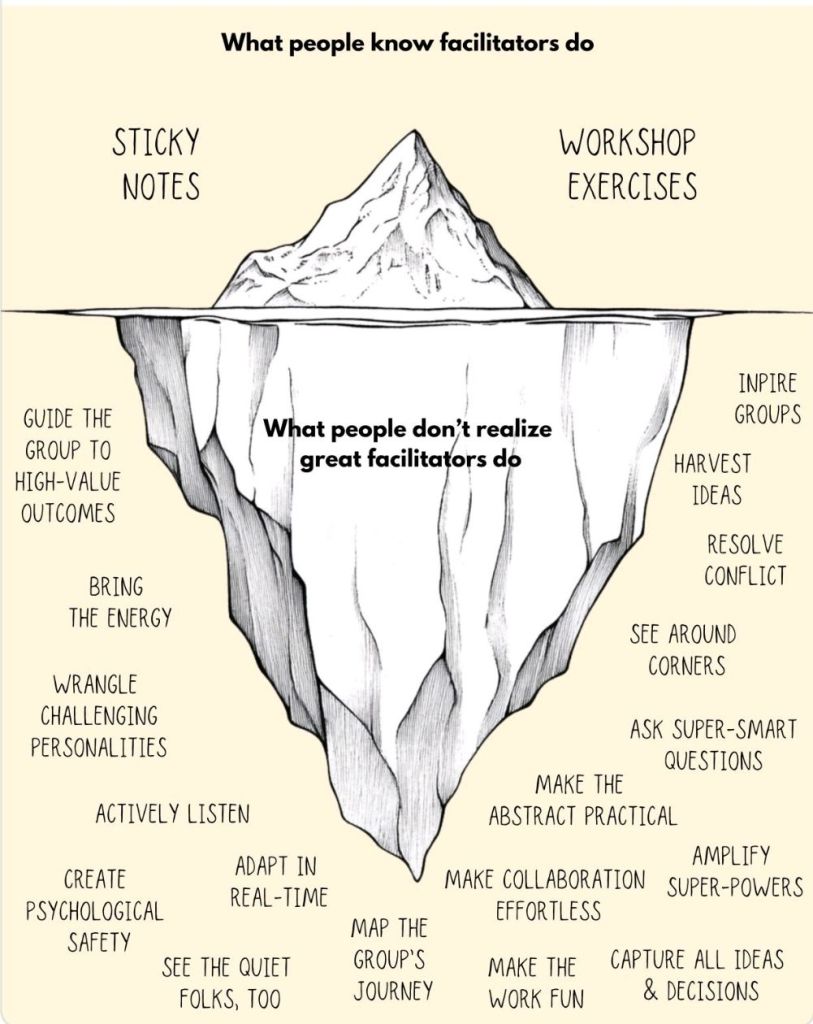

How we communicate as leaders and decision makers is always important. Understanding how that communication is going to be received and processed, not just based on our intent, is a crucial factor that we often forget to evaluate as we focus so much on the message itself. The Spotlight Effect means that we need to think about how others receive the message, both when things are going well and when the individual may be in a more anxious state. In order to do this effectively, timing, word choice and content are all key. Choosing words that are unambiguous and judgement free is important. Taking time to explain decision making, so that individuals don’t feel like they are over looked, unrecognised, or punished, can avoid mis-understandings. Reading your audience, so you are having the communication at a time when people are able to engage with it, can also be crucial.

When individuals are interacting and responding to us, we should be cognisant of how their current thought processes are influencing how they react. It is critical to not fall into spotlight behaviours ourselves, and therefore focus on really listening to responses and actively checking on our perception of what it is that we are being told. Sub-text is key, especially if others feel like they aren’t in a position where they can be heard.

What can it mean for your well-being?

Like many moments in life, self awareness is key. Understanding and questioning how your perception of situations and your sense of self is driving your behaviour is critical to trying to make the best decisions for yourself, both personally and professionally. I think I’ve covered in this post that I am far from perfect in this regard. I can often recognise that my perceptions are skewed but cannot always enable the next step of putting that to one side and so still feel the resulting anxiety and other effects. The thing that I can usually manage, is to be aware enough that I don’t make decisions or actions on the basis of what I know is inefficient thought processes.

As well as being aware of your thought processes it is also worth being aware of your areas of focus. Are you spending a lot of time placing resource into any one thing? Is this use of resource appropriate or is it due to obsessive or faulty thinking? It’s easy to get drawn into something without realising how much energy it’s taking or quite how far down the rabbit hole you’ve travelled. A level of self-check in terms of being conscious about where you’re investing your focus and energy can save you from wasting what resources you have on a problem that may not be as you perceive.

None of us get this right all the time. When you find yourself realising you’re staring into the glare of the spotlight and all that comes with it, the most important thing is to give yourself a break by being kind to yourself. We all have moments where we’ve mis-read situations, been deaf to the commentary of others, or reacted based on an ego centric focus. It happens. The key things are the actions we take as a result of the realisation of the bias we’ve engaged with and how we develop the self awareness to do better next time. Accepting that the lessons learnt are the most constructive way forward, rather than wasting more energy on self recrimination.

How do we sense check?

Knowing that we are unreliable witnesses to our own lives can offer a major step forward in being able to improve our insight into the reality of our situations, rather than interpreting it so strongly through our own glasses, be they rose or darkly tainted. I find there are three key moments when active engagement with self reflection is key in order to try to reduce ego centric bias from my thinking:

- Checking expectations

- Checking perception

- Checking responses

Having clear stop and reflect moments at these key points can help reduce the Spotlight Effect, but also enable me to realise when I’ve already veered into spotlight territory to support me in trying to step out of the glare. I would also flag here, not to under estimate how much other people can help with these moments of reflection. I drive Mr and Mummy Girlymicro crazy with my constant need to talk through my thought processes, especially when I’m struggling to gain clarity or re-frame my thinking from a less ‘me’ focus. Having those trusted companions who can assist, and if needed call you out on your ego centrism, for me, is just an important thing in all aspects of my life.

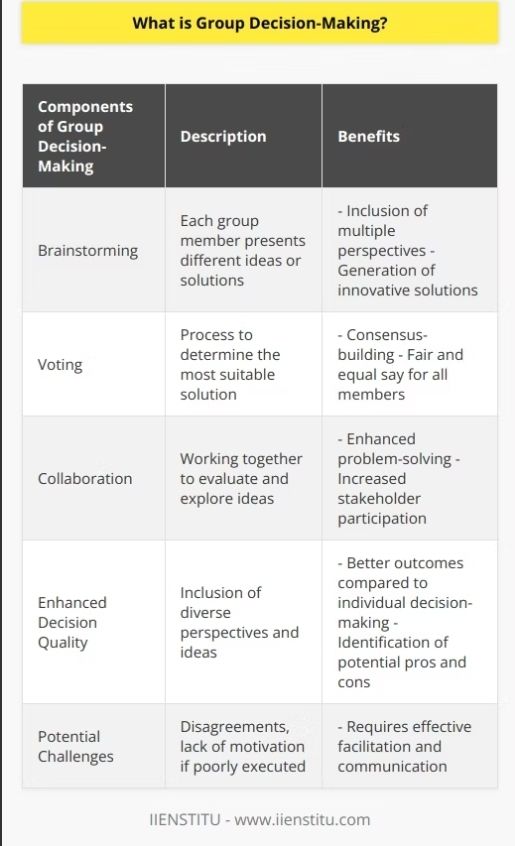

How can understanding lead to better conversations?

One of the major interventions we can build into our interactions in order to prevent the Spotlight Effect impacting our leadership and decision making is trying to ensure that we have better conversations, in order to understand the drivers of others and embed their life experience in our relationship building and social interactions. So how do we have better conversations? How do we ask better questions that enable us to engage better in order to truly be interested rather than trying to be interesting. The main switch is to the use of open ended questions so our conversations can be driven by curiosity, not by the need to re-enforce concepts we already hold.

Focus on the use of questions that start with:

- How?

- What?

- Why?

You can even frame questions by saying ‘tell me about’ or ‘describe’. By actively listening to the responses and following up with appropriate further open questions based on the answers, you can build both a deeper understanding and trust.

Embedding curiosity at the heart of our leadership leads to unexpected insights and outcomes that you couldn’t achieve alone. So, whenever you find yourself too focused on how you believe the path should be walked, phone a friend and ensure that you step out of the spotlight in order to see what different routes may be available in order to move forward in ways that benefit everyone involved. Only then can we demonstrate leadership which aspires to help everyone, rather than choosing pathways that benefit us alone.

All opinions in this blog are my own