After my sojourn in my Ivory Tower on Friday, I wanted to get back to posting about antibiotics this week. Although I only really intend to post once a week, I thought it might be useful, if I’m going to be posting about antimicrobial resistance (AMR), to post a little bit about what an antimicrobial is.

What is a microbe?

My husband reminds me I use a lot of words interchangeably; That can make it hard to follow. First of all, I should explain that microbiology and microbe are ‘cover-all’ terms, including viruses, bacteria, parasites and fungi. You can then sub-group within that and talk about parasitology, virology, bacteriology and mycology (study of fungi).

What is an antimicrobial?

Antimicrobial = a medicine that inhibits the growth of or destroys microorganisms

Antimicrobials don’t just work against bacterial, they work against microbes (hence the name). That said, one antimicrobial won’t work against all sorts of microbes – it’s just a generic cover-all name. Specific groups work against specific types of microbe:

- Antiviral = works against viruses

- Antibacterial (often called antibiotic) = works against bacteria

- Antifungal = works against fungi

- Antiparasitic = works against parasites

That said, most of the time when people are talking about antimicrobial resistance they are actually talking about antibacterial resistance, so that is what this post is going to focus on.

Antibiotics work in two main ways. They are either:

- Bacteriostatic = inhibits the growth of bacteria

- Bactericidal = kills bacteria

Whether an antibiotic kills a bacteria or just stops it reproducing is important when we are deciding which one to choose clinically. For example, if I have a patient who has no immune system, or whose immune system isn’t working, I can’t use an antibiotic that just stops the bacteria growing, as their own immune system won’t be able to attack the remaining bacteria. In this case I need to use an antibiotic that kills the bacteria.

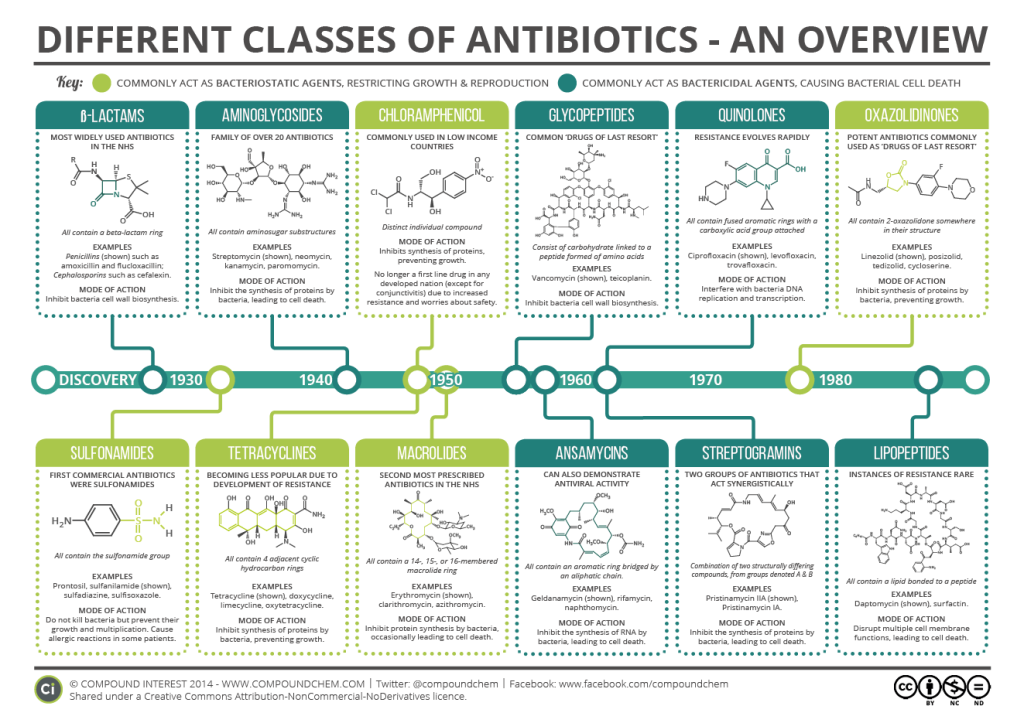

Below is a diagram of some of the different groups or classes of antibiotics, colour coded with whether they KILL (dark green) or STOP GROWTH (light green).

Whether an antibiotic kills or stops growth really depends on what part of the bacteria it targets. It is very hard for a bacteria to survive if it has a hole in it’s cell wall (like us having a massive hole in our skin), and so antibiotics that target the cell wall, like penicillin (B-lactam), are usually bactericidal. Antibiotics that target protein synthesis, which is what bacteria need to reproduce and grow, are usually bacteriostatic, like erythromycin (Macrolide).

One of the other considerations when deciding which antibiotic to use is whether we are using it to treat an infection (treatment) or to prevent an infection occurring (prophylaxis). We use prophylaxis if you are undergoing certain types of surgery or when we know you’ve been exposed to certain bacteria or other microbes. This is aimed at reducing any small numbers you may have on board to prevent infection/symptoms. These doses are often different to treatment doses and we will usually try to give the medicine orally (i.e. pills) rather than by injection or by IV, if possible.

As antibiotics usually accumulate in the system or the area of the body we’re trying to target that is infected, it is really important that you complete the course (total number of days and doses) that are given to you. If you don’t do this and stop when you’re feeling better, the small number of bacteria that are left can then grow and multiply again, causing you to need another course. Worse than this, potentially, is that the bacteria may then become resistant to the first antibiotic.

Antibiotic resistant means that the bacteria is no longer affected by the antibiotic (i.e. doesn’t work at all or works less well).

This means that you may need to be given other antibiotics which are not as ideal, i.e. more side effects or not taken orally. Antibiotic resistant doesn’t mean that your body is resistant to the antibiotic, it merely describes the bacteria no longer being impacted.

As well as some bacteria developing resistance to an antibiotic due to exposure, some bacteria are intrinsically (naturally) resistant to certain antibiotics. In some cases this is because of the features certain bacteria have. One example of this is that bacteria are divided into Gram-positive and Gram-negative (plus some oddities like mycobacteria) based on their cell wall. Antibiotics like Vancomycin don’t work on Gram-negative bacteria as the molecule is too big to pass through the cell wall.

If you’d like more details about different antibiotic classes, the antibiotics within them, how they are used and mechanisms of resistance, feel free to download the PDF below which I prepared as part of FRCPath revision:

Some points to reflect on:

- Antimicrobial is a term used to cover drugs for parasites, fungi, bacteria and viruses

- Antibiotics can be either bacteriostatic or bactericidal

- Antibiotics target different parts of the bacteria and that is what makes them either kill or inhibit growth

- Antimicrobial resistance can be acquired or intrinsic due to the features of the bacteria

All opinions in this blog are my own

[…] is a drug called azithromycin and its from a class of antibiotics called the macrolides (see my A Starter for 10 on Antimicrobials […]

LikeLike

[…] on treatment or management of the infectious cause i.e. antimicrobials or non antibiotic management such as […]

LikeLike

[…] is when the individual bacteria are not affected by the antibiotic or it works less well (see my introduction to antibiotics post for a bit of a […]

LikeLike

[…] is when the individual bacteria are not affected by the antibiotic or it works less well (see my introduction to antibiotics post for a bit of […]

LikeLike

[…] on treatment or management of the infectious cause, i.e. antimicrobials or non-antibiotic management such as […]

LikeLike

[…] on treatment or management of the infectious cause, i.e. antimicrobials or non-antibiotic management such as […]

LikeLike